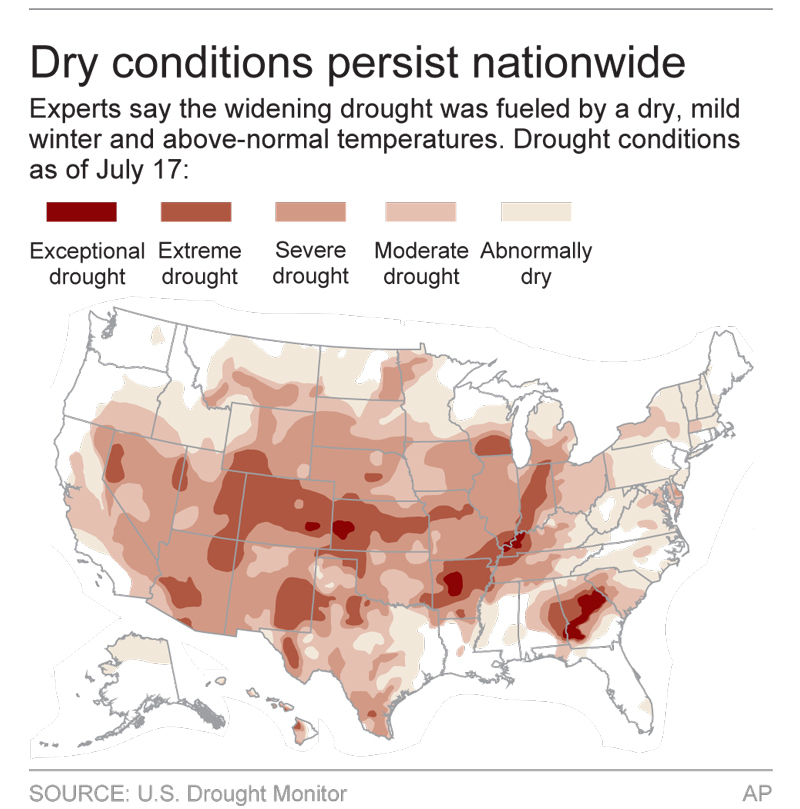

The United States is experiencing its worst drought since 1956. Amid seemingly endless heat, crops bake and livestock pant.

Politically, though, the brutal weather is manna from heaven for the agriculture lobby and its amen chorus on Capitol Hill.

At last — the perfect excuse to pressure House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, into speeding consideration of a subsidy-rich, five-year farm bill!

“What do we do? We need to pass a farm bill,” said Senate Agriculture Committee Chairwoman Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., who already has shepherded a version of the legislation through the upper house. Actually, the flawed bill is irrelevant to the farm belt’s current predicament, and it could perversely magnify losses from future natural disasters.

The worst damage is to the corn crop, 80 percent of which goes to feed animals. (Sweet corn for people “is not being heavily affected by adverse weather,” according to the Agriculture Department.) Corn supplies already were tight before the drought, so feed costs for pork, dairy, chicken and beef producers are headed up.

But keep the potential hardship to producers and consumers in perspective. “U.S. farmers face this drought in their strongest financial position in history, buoyed by less debt, record-high grain and land prices, plus greater production and exports,” reported Christine Stebbins of Reuters, after a thorough canvassing of industry and government experts.

Farm losses should be far smaller than those suffered in the last big drought, 24 years ago.

In fact, the Agriculture Department estimates that government-subsidized crop insurance covers more than 80 percent of farmland planted with major field crops — at least two of which, wheat and cotton, appear pretty much unaffected by the dry weather anyway.

Dairy farms are the least likely to be in drought-ravaged areas, the USDA reports, and many of them enjoy federally subsidized insurance against rising feed costs.

The consumer may not notice much in the way of higher prices for 10 to 12 months, according to the USDA; meanwhile, meat may get cheaper, as producers slaughter animals rather than feed them expensive grain.

Overall, the USDA estimates that a 50 percent increase in corn prices could boost retail food prices by 0.5 to 1 percent — nothing to celebrate but hardly devastating.

And before Congress rushes through the farm bill, it’s worth reflecting on all the ways existing policies worsen the drought’s impact.

More corn would be available for animals if not for federal ethanol mandates. One reason for drought- and flood-related crop losses is that federally subsidized crop insurance encourages farmers to cultivate marginal land and engage in other risky practices, knowing that taxpayers will, in effect, bail them out. Both the House and Senate versions of the farm bill would increase subsidized crop insurance, thus accentuating this moral hazard.

Given farming’s vulnerability to extreme weather, against which private insurance may not exist, there may be a limited role for government protection from genuine catastrophe. This drought might or might not qualify, depending on what crop you’re talking about and where it’s planted.

Otherwise, farmers should have to hedge as other businesses do: by diversifying their product lines, purchasing insurance at market rates, leveraging assets or maintaining cash reserves. For decades, federal policy has been training farmers to depend on government instead, and taxpayers have been picking up the tab.

Editorial by The Washington Post

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.