What’s a good price for a 60-watt-equivalent light bulb that uses 75 percent less electricity than a standard incandescent and can last 11 years?

How about a dime?

That’s what Walmart supercenters are charging. The stores are featuring a 10-pack of General Electric compact fluorescent light bulbs for $1.

Prefer a high-tech, light-emitting diode bulb that provides similar brightness for even less energy? Home Depot has launched a sales campaign for a new LED that sells for $12.97. If you screw it into a lamp socket in a baby’s nursery today, the bulb is expected to still be working when the kid’s in college.

These two bulb promotions illuminate two distinct choices for energy-efficient lighting in Maine. And they raise a question: Should you spend 10 cents, or $12.97, for roughly the same amount of light?

The answer seems to be that CFLs are an interim technology and a steppingstone to a world lit by light-emitting diodes, which are quickly becoming more affordable.

“The CFL is really about saving energy at the lowest cost,” said Michael Stoddard, executive director of Efficiency Maine. “With LEDs, it’s more about market transformation, getting customers familiar with LEDs and driving down the price over time.”

Lighting accounts for less than 10 percent of total home energy use. But Efficiency Maine, which runs the state’s conservation programs, has found that switching from incandescent bulbs to CFLs is the most cost-effective energy investment a homeowner can make.

Since 2004, the agency has tapped a fund paid for by electric ratepayers to help subsidize 8.7 million bulbs. It even distributed 400,000 CFLs last year to low-income Mainers, through the Good Shepherd Food Bank. The aggressive promotions have helped Maine achieve one of the highest concentrations of CFLs in the country.

Despite all this, a recent survey revealed that 83 percent of sales in Maine last year were not CFLs, but energy-eating incandescent bulbs.

It seems that many people have never warmed up to CFLs. Some early models were outsized spirals that displayed a harsh light color, took time to fully illuminate and didn’t work with dimmers. They also contain mercury, so they need to be carefully recycled.

Current CFLs are much-improved; several models give off a warm light and can be dimmed. But many people remain turned off, said Jim Ford, an assistant manager at the Home Depot in South Portland.

“I’m not surprised,” Ford said of the Efficiency Maine survey. “Maine people don’t like change, and the number one reason I hear from customers is they’re still not happy with the way CFL light looks.”

That feedback has Home Depot focusing on LEDs, which Ford said now outsell CFLs three-to-one. LEDs are stacked along prime shelf space in the light bulb section, which at Home Depot runs an entire aisle.

Behind this trend, an industry expert says, is a scramble for market share. The days when a light bulb burned out in a year and needed to be replaced are fading fast.

“There are roughly 4.4 billion screw-in sockets in the United States,” said Terry McGowan, director of engineering at the American Lighting Association. “Manufacturers know they have one chance, because it could be 25 years before they’re available again. So they’re doing everything they can to fill those sockets with their products.”

This spring, the Home Depot chain began an exclusive partnership with Durham, N.C.-based Cree, Inc. to promote a new, omnidirectional LED bulb. It has the same warm, white light and shape of a traditional incandescent bulb, but will last for 20 years and use one-sixth of the electricity. A Cree display in the South Portland store proclaims: “The biggest thing since the light bulb.”

The Cree 40-watt-equivalent bulb, rated at 6 watts, is selling for $9.97. It emits 450 lumens, a measure of brightness. A 60-watt-equivalent that burns 9.65 watts and throws off 800 lumens costs $12.97. These prices are two or three times less than comparable LEDs were selling for a couple of years ago.

“We think that bulb is a game-changer for us,” Ford said.

Cree has price competition, however. The store also carries a Philips 60-watt-equivalent LED for $9.97, and a 40-watt-equivalent for $4.97.

“They’re selling out as soon as I can get them in,” said Paul Goudreau, a master electrical specialist at the store. “I can barely keep them on the shelves.”

Goudreau said he tries to enlighten customers who are unsure of the fast-changing options. That’s what he did when Gloria Bush of Gorham came by, looking to replace a bulb that burned out after 18 months in a recessed fixture in her kitchen.

Goudreau inserted a 50-watt equivalent Ecosmart LED into a display, so Bush could see the light comparison with an incandescent. They appeared identical, but the LED is only 8 watts and has an average life expectancy of 23 years. The downside is that it costs $24.97, due in part to its special recessed-socket base.

Bush’s kitchen has six sockets, but she decided to buy two LEDs and see how they perform.

“I didn’t know what I was looking for, except the size,” she said. “I learned a lot.”

That’s typical, Goudreau said. He suggests that people experiment with LEDs by re-lamping a room they use frequently.

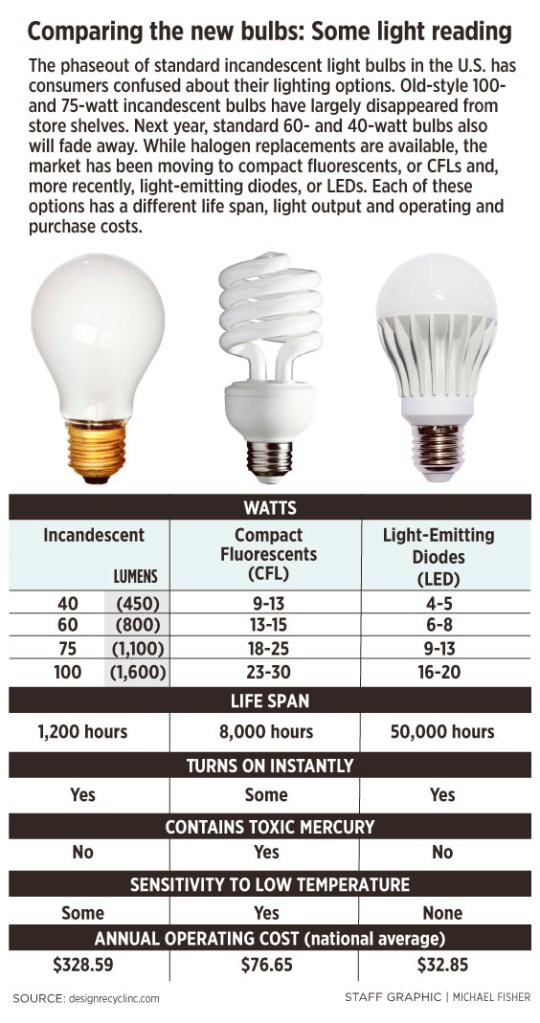

This transformation is happening because governments around the world are phasing out traditional incandescent bulbs and encouraging more-efficient alternatives. In the United States, old-school 100- and 75-watt bulbs have largely disappeared from store shelves, and their 60-watt cousins will go away next year.

The National Electrical Manufacturers Association reported this month that shipments of incandescents fell 40 percent from last year, to a record low. But incandescents aren’t actually banned, as some critics complain. They’re being reborn with a halogen technology that, by law, must use at least 28 percent less energy. So a former 100-watt bulb now is sold as a 72-watt replacement.

Before they went away, boxes of the old-style 100- and 75-watt bulbs were scooped up by people who planned to stockpile or resell them. Now these folks are hording the 60- and 40-watters, Ford said.

“If we have the opportunity to talk to customers, most of the time we can talk them out of buying incandescent bulbs,” he said.

Incandescents are still being highlighted at the Scarborough Walmart. But right next to them, 10-packs of the General Electric CFLs for a buck are on display.

Walmart clearly promotes CFLs over LEDs. It has other sweet deals on CFLs, promoted with tags that read: “Special pricing provided by Efficiency Maine.” For example: A three-pack of 10-watt General Electric mini-spirals costs 75 cents. A four-pack of 14-watt Great Value soft-white spirals is 88 cents.

It’s not clear how Walmart arrived at its 10-for-a-dollar CFL promotion. The Scarborough store manager declined to answer questions, and a corporate spokesman said the company doesn’t discuss pricing and sales strategies.

“I think you go to Walmart for low prices, primarily,” said McGowan at the home lighting trade group.

But despite giveaway pricing, national CFL penetration mirrors Maine’s experience — only 20 percent of homes have them, McGowan said.

“LEDs are going to be the ultimate solution,” he said. “CFLs may be the low-price, commodity thing for the workbench or garage.”

Even as standard LEDs fall in price and gain market share, manufacturers are trying to interest consumers in another bright idea: Smart light bulbs. The Philips Hue, introduced late last year, can be controlled through an iPhone or iPad and a home’s wireless network. Up to 50 bulbs can be connected, but if you want to get smart slowly, a three-bulb starter pack and digital “bridge” sells for roughly $200.

Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or

tturkel@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.