By DOUGLASS K. DANIEL

Associated Press

Civil War photographer Mathew Brady largely taught himself the finer points of the two pursuits that have linked his name to history: taking pictures and self-promotion. The son of Irish immigrant farmers had a talent for cajoling presidents, generals and business leaders to sit before his camera.

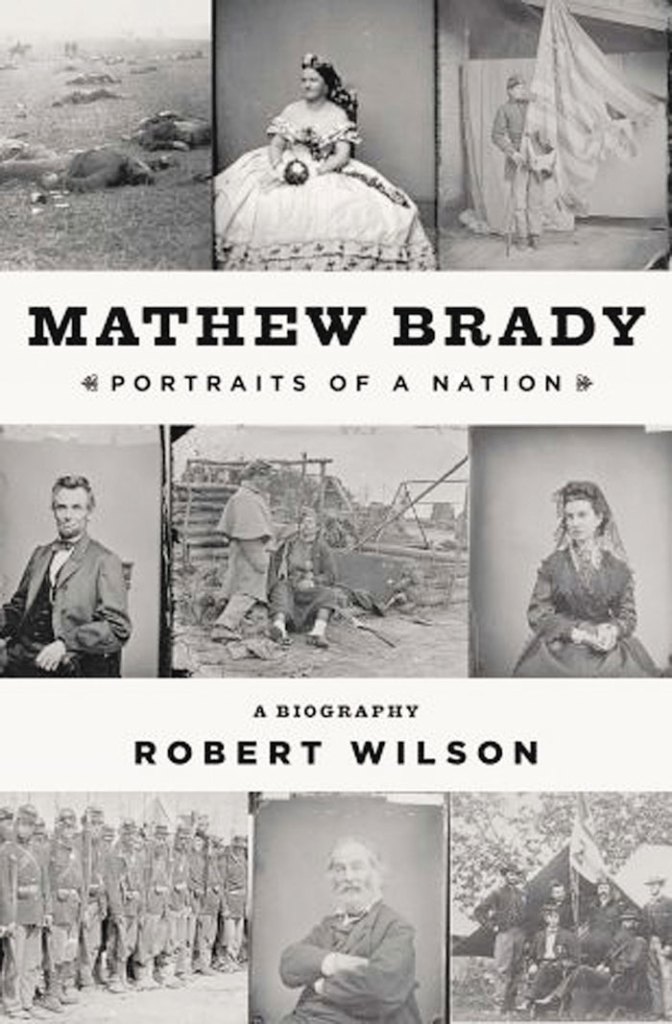

Other than his birth around 1823 in Warren County, N.Y., little is recorded about Brady’s early life, a challenge for biographer Robert Wilson. Yet readers of “Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation” probably benefit from this dearth of personal information. Wilson moves quickly to what matters most — Brady’s role in how we see America in the mid- to late 19th century.

Timing was on Brady’s side when, as a teenager, he left the countryside for the big city around 1840. The early photographic process called daguerreotype, invented in Paris, arrived in New York just ahead of him. He may have taken lessons in the technique while supporting himself as a clerk at a fabric store.

In 1844, Brady opened a photographic studio that produced portraits, and after five years of success, he started a studio in Washington. Wilson makes a compelling case that Brady eventually rose above a sea of artistic entrepreneurs offering photographic portraits because he learned, and often advanced, the latest techniques. As important, he had a pleasing manner that put subjects at ease during the time-consuming process of getting a picture taken.

Brady also understood how publicity worked back then. The Hall of Fame in his Broadway studio featured a gallery of celebrities — a subtle pitch for others to pay a few dollars for portraits of their own. Few would not want to sit for the studio that photographed war heroes like Gen. Winfield Scott, naturalist and painter John James Audubon and the elderly former first lady Dolley Madison. In 1849, President James K. Polk allowed Brady to take his photograph in the White House, as did his successor, Zachary Taylor, a sign of Brady’s growing reputation.

A decade later, when the nation seemed destined to fracture over slavery, Brady was, as Wilson puts it, at the “height of his fame as a photographer of celebrities.” His 1860 photograph of a beardless Abraham Lincoln — Brady pulled up the collars on Lincoln’s shirt and coat, probably to hide his long neck — helped to make the presidential aspirant known around the country.

The Civil War created a strong demand for photographs of soldiers in studio settings and in encampments. The custom of the time was for the studio’s owner to take the credit, not those working in the studio or in the field. While Brady shared credit with his photographers some of the time and traveled to battlefields such as Gettysburg, his name is associated with many photographs he didn’t take.

Brady’s experience at Bull Run — he lost his equipment in the chaotic retreat that marked the North’s first major battle — may have cooled his eagerness to ask those working for him to photograph close to actual fighting. As the war continued, photographic images of dead soldiers, slain horses and other post-battle carnage brought to the public a face of war most had never seen.

Wilson argues that Brady’s role in promoting wartime images through his studios and the print media was crucial to their impact even if he wasn’t the man behind the camera.

With Wilson’s keen analysis of Brady’s life and times and the images that defined them, “Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation” brings into sharp focus a fascinating footnote to American history.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.