The guilty plea by Chris Knight, the North Pond Hermit, along with news that three persons have been charged with criminal trespassing for allegedly setting up house in an abandoned building in Livermore Falls, have once again shown a spotlight on the practice of squatter interaction with private premises in Maine.

It’s also an occasion to take a look at some other instances of such alleged conduct. Indeed, it’s an instance in Maine that gave rise to the first recorded use of the term “squatting,” in a letter to George Washington in 1788 from James Madison, when he lamented the existence of the phenomenon in Maine.

Squatters seem to fall into two basic sets of behavior patterns: those, such as the North Pond Hermit, who do so clandestinely and those, such as like the pioneer Maine settlers in Washington’s time, who do so openly.

Clandestine Squatting

Somehow, those who squat secretly are the subject of the most popular interest. Indeed, the revelation of Knight’s 27-year adventure this spring captured international headlines and has been made the subject of a full length feature movie documentary. Knight’s folk-hero status is tainted by the many theft and burglaries he acknowledged committing during his decades’ long retreat. If he’d hunted and fished for survival, he likely would have escaped the clutches of the criminal justice system, even though there’s a Robin Hood-like respect occasionally afforded someone who makes off with the goods from those in more affluent circumstances.

Knight’s under-the-radar escapades have counterparts elsewhere. Some years ago, two Colby College students — unable to afford the institution’s room and board — set up a poly hut in a wooded area on Mayflower Hill. Though the makeshift dwelling was, like Knight’s, designed to be obscured from view, campus authorities got wind of it and wound up raiding the place and having it torn down.

More successful at bypassing university housing, and illustrating how to perhaps avoid squatter status, however, was a Duke University graduate student named Ken Ilgunas, who secretly lived for two years in an old Ford Econoline van. The university’s gym and library helped spare him deprivations. Ilgunas has since gone public with a book about his unusualy living circumstances, “Walden on Wheels,” at the time (2009-11), he was intent on keeping the venture secret.

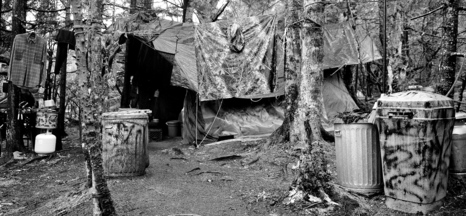

Most, however, who undertake clandestine lifestyles are not likely to write a book about it. Tunnel dwellers in major cities such as New York and Las Vegas come to mind.

Open Squatting

Those accused of setting up house in an abandoned building in Livermore Falls allegedly seem to have been taking a page out of the book of the more traditional “open” squatters, those who do so a bit more conspicuously than Knight and his ilk. Open squatters’ living arrangements usually are more temporary. Some, such as those in the “Occupy Wall Street” or “Occupy Maine” movements, engage in squatting as part of a political protest statement, usually occupying public property.

Other open squatters do so out of a desperate pursuit for affordable housing, typically in home or apartment dwellings vacated by families facing foreclosure or eviction, sometimes catching inattentive or absent landlords off guard.

Still other open squatters engage in the process with less noble motives. Such appeared to have been the case a year ago in Bangor when authorities came across four transients in an un-rented apartment who told police they “came to party.” The rightful owner of the property wasn’t far away, and the four were arrested.

In Maine and elsewhere, common squatting episodes in the recent foreclosure crisis have featured people who occupy “zombie homes,” from which both legitimate home owners and foreclosing banks have simply walked away. The reasons for abandonment include depressed market conditions and deteriorated conditions that typically afflict dwellings that are financially “under water,” where the amount owed far exceeds the salvage value.

The practice begins when homeowners who stop making mortgage payments throw in the towel, sometimes concurrent with a divorce or other family domestic challenge, and move out. Meantime, the foreclosure process, which often can take many months to complete, leaves the property in limbo. By the time the bank gets to the brink of seizing the property, it has suffered such a further decline in value because of the inability or unwillingness of anyone to perform repairs that the bank itself also takes a walk.

According to the real estate data company Realty Trac, Maine is one of 11 states with a high incidence of vacant foreclosure properties. This is attributable in part to the longer-than-usual time period it takes to complete a foreclosure in Maine, which according to Federal Home Loan Board statistics is about 570 days, giving the state the sixth-longest foreclosure time in the country.

Though by no means all the vacant properties are occupied by squatters, their abandonments are tempting to them.

The nature of foreclosures is yet another reminder of how squatting has continued in Maine from 1788 until now.

Paul H. Mills is a Farmington attorney known for his analyses and historical understanding of public affairs in Maine. He can be reached by email: pmills@myfairpoint.net.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.