Lisa Lawlor spends most of her waking hours in bed, swallowing 25 pills each day to manage numerous Lyme disease-related symptoms. She receives antibiotics three times per day, intravenously into her left arm. Although she can walk, she often uses a wheelchair because she is so weak. The joint pain, inflammation and fatigue never completely goes away for the Saco resident, and she often experiences nausea.

Lawlor’s symptoms are worse than most Lyme sufferers, but she’s far from alone in coping with Lyme disease or its aftermath.

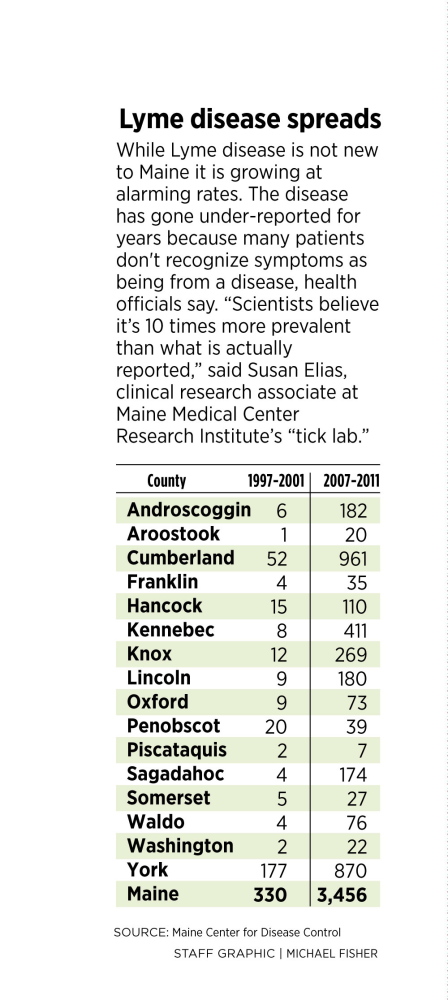

While Lyme disease is not new to Maine, the number of people diagnosed each year is growing at alarming rates. Public health officials say broader public awareness, more research into how the disease works, and tools to treat and prevent it are needed.

It took Lawlor two years to find out she had Lyme disease, even though she reported a rash to doctors within a week after noticing it in 2011. A tick probably bit her right ankle at her camp in Island Falls, but she was not diagnosed with Lyme disease until 2013.

The rash on her ankle was misdiagnosed initially as a spider bite, said Lawlor, 43, and tests for Lyme at that time came back negative. After unsuccessfully trying to manage persistent and worsening symptoms, she was tested again and diagnosed with Lyme disease in August 2013.

Lyme disease diagnoses have exploded in recent years to a record high 1,376 cases in 2013, with this year shaping up to be similar to last year, according to officials with the Maine Centers for Disease Control. But the ticks probably have gotten under many more Mainers skins.

“Scientists believe it’s 10 times more prevalent than what is actually reported,” said Susan Elias, clinical research associate at Maine Medical Center Research Institute’s “tick lab.” If true, about 1 percent of Mainers per year will have contracted Lyme disease over the past two years.

The reason: Lyme disease, a bacterial infection spread by ticks, is often under-reported by patients. The symptoms run the gamut, with some people shrugging off flu-like symptoms after a week or two and others suffering for years with severe problems.

Public health officials are now grappling with a widespread disease that just a decade ago was diagnosed in fewer than 100 Mainers per year.

A new report by the National Wildlife Federation said warming global temperatures, caused by fossil fuel consumption, have increased the habitats available for ticks. Warmer winters, hotter summers and high temperatures that extend into autumn make conditions ripe for ticks to reproduce and spread.

Elias said research at Maine Med’s vector-borne disease laboratory — the “tick lab” — corresponds with the report’s findings.

“We have 25 years of data, and the tick abundance by year is associated with warmer weather,” Elias said. “We tend to have more ticks when we have a warmer year.” Even though last winter was cold and long, researchers have said the extra snow acted as an insulator for ticks.

Dr. Sheila Pinette, director of the Maine CDC, spoke at a news conference in Portland hosted by the Natural Resources Council of Maine on Tuesday to discuss what people can do to prevent tick bites and to address them when the occur.

Mainers are 30 percent less likely than people across the United States to tell their doctor about the bulls-eye rash that is a common sign for Lyme disease, said Pinette. Some may not recognizing it as dangerous, she said.

“Mainers are hardy people,” Pinette said. “They get muscle aches or joint pain, and they just think it’s because they’re getting old.”

AVOID THE BITE

Elias said that the first step residents can take is to stay away from tick habitat in their backyard, by not approaching any wooded areas or underbrush. Spraying rosemary oil near the perimeter may help control ticks and will not damage the environment.

She said local and state governments could work to reduce the deer herd to about 12 deer per square mile — some areas of southern Maine have more than 50 deer per square mile — also controlling the tick population. And Elias said controlling the barberry bush, an invasive plant that’s prime tick habitat, also would be helpful.

Individually, wearing pants, long-sleeved shirts and insect repellent, and examining your body for ticks after venturing into the woods can help prevent tick bites.

A vaccine would also go a long way toward preventing Lyme disease. Baxter International, an Illinois pharmaceutical company, has completed early clinical trials on a Lyme vaccine, but the research is now “on hold,” according to a company spokesman. He declined to say why or comment further. A vaccine was available in the late 1990s and early 2000s but was pulled from the market after some patients complained of arthritis.

Maine Med is working with Yale University to evaluate the effects on people who are infected with more than one type of bacteria from a single tick bite. The ticks can transmit up to five types of bacteria into the host body.

Also, voters in November will be asked to support an $8 million bond that would pay to build a laboratory at the University of Maine for monitoring Lyme disease and other health threats related to mosquitoes, bedbugs and ticks.

SEARCH FOR TREATMENTS

Medical experts say the antibiotic treatments for patients are most effective when Lyme disease is caught early.

Dr. Robert Smith, an infectious disease specialist at Intermed in Portland and co-director of Maine Med’s “tick lab,” said that when patients come to him with rashes, he will treat for Lyme disease even when the disease is only suspected. Lyme disease tests given within 30 days of a tick bite often come back negative even when someone is infected. Tests performed later are more accurate, Smith said, but it’s best to give treatment as soon as possible.

“We will err on the side that they have Lyme disease,” Smith said. For patients who don’t notice the disease in the early stages, treatments are effective but sometimes slow to ease symptoms.

“Some symptoms may linger after treatment, but a relapse of the infection striking again is quite rare,” Smith said.

More controversial are long-term antibiotic treatments, such as the course that Lawlor is taking. Lawlor has been on antibiotics for about three months. Smith said national studies have not shown long-term antibiotic treatments to be effective for Lyme disease and may be counterproductive.

But Lawlor said she has felt better this summer than she has in two years and is able to now occasionally leave her the house.

While the long-term antibiotic treatments have not been proven, Pinette said she doesn’t blame patients for trying alternative methods when other treatments aren’t working. And she said scientists have much to learn about Lyme disease.

In fact, some people finish their course of antibiotics but still suffer from symptoms likely because the bacteria has damaged their immune system, causing what is known as post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome, Pinette said.

Angela Coulombe, of Saco, said doctors at first were dismissive of her after a round of treatments did not improve her condition when she contracted Lyme disease seven years ago. She did not catch the disease in the early stages, believing she had aggravated an old running injury.

“I couldn’t lift my arms over my head or dress myself,” Coulombe said. “I was nearly an invalid.” When she was told no other treatments were available, she switched doctors.

After going to a different doctor a month later, Coulombe was given antibiotics for two months, followed advice to change her diet and used Eastern medicine to help control her symptoms. Progress was slow but noticeable.

“It felt like it took a year to really turn the corner,” Coulombe said. “One week I couldn’t lift an empty laundry basket off the floor, and the next week I could. Little things like that.”

Coulombe is back to running, and she is competing in marathons.

“I am one of the very lucky ones,” said Coulombe, 49, of Saco.

Lawlor may never recover to the level that Coulombe has, but with the help of family and friends, her outlook has improved. A close friend, Lee Faulkner, helps her with daily living, making her food, letting her lean on him when she walks and taking her places. As recently as this spring, Lawlor suffered from numerous seizures per day, but this summer the seizures have stopped.

Her husband, David Lawlor, said that he’s noticed an improvement in health and attitude.

“She has had more good days lately than bad,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.