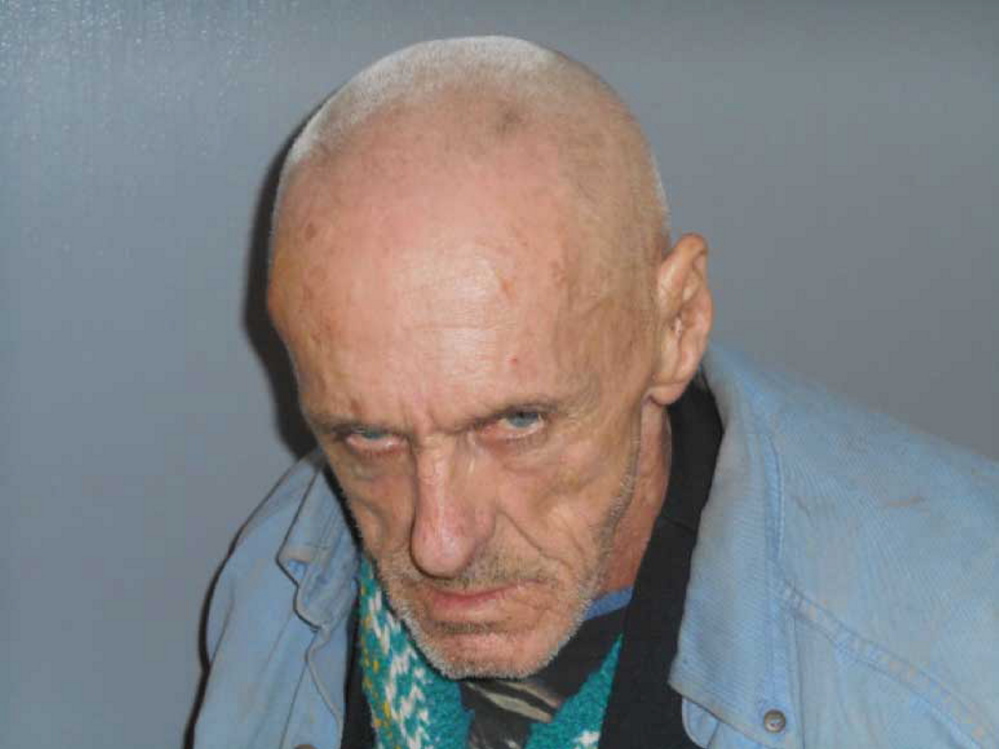

Dana Kitchin was by all accounts a good man — when he was taking his medicine for bipolar disorder and the pain in his legs was controlled.

And he was generous; perhaps too much so at times, according to his family. He would get his disability check and spend it to host a barbecue for the entire neighborhood of Butler Court in Waterville, where he lived.

“He had a very big heart. He’d give you his shirt off his back,” said his sister, Debbie DeYoung, 60, of Fairfield.

Kitchin was found dead Dec. 12 in his jail cell at the Kennebec County Correctional Facility in Augusta. It appeared he died of natural causes, according to authorities, who also say there was no prior indication that Kitchin had a medical condition.

But his family and at least two inmates at the jail say that’s not so. Kitchin’s family says he should not have died the way he did this month, after pounding repeatedly on a jail cell door and yelling for help. At least two jail inmates told the Morning Sentinel that they recall Kitchin shouting that he needed to go to the hospital.

His sister, Joan Cuares, 62, of Fairfield, said she thinks the system failed him.

“He was not an angel by no means,” she said, “but he didn’t deserve to be neglected like this.”

Kitchin, 64, was often in pain from the blood clots in his legs or being off his bipolar medication, causing him to act bizarre, say nasty things and lose control of himself. The family would call police and crisis workers, he’d be taken to the hospital and sometimes get arrested for his disorderly behavior and be transferred to jail. Recently, he was admitted to the behavioral health ward at the hospital, but he was released a few days later, even though he still was talking about things that did not make sense, his family said.

When his longtime live-in girlfriend could not tolerate his actions a couple of months ago, he started living outdoors. His sisters paid for him to stay in a hotel room, but he invited homeless people to stay in his room, and he went out to live on the streets.

“He’s never been right in the head — never what we would call ‘right,'” DeYoung said. “He’s been on disability a lot of years.”

ON A STRETCHER

Kitchin was found unresponsive in his observation cell at the Kennebec County jail at 3:55 p.m. Dec. 12.

By the time rescue workers arrived, he was dead. An autopsy was performed on his body, but results are not expected for a month or two, according to family members.

Kennebec County Sheriff Randall Liberty said at the time that it appeared Kitchin died of natural causes and there had been no prior indications to jail staff that Kitchin had a health problem that needed to be addressed.

Kitchin, who had been arrested on criminal trespass charges, had been placed in an observation cell at the jail because he was disruptive, making loud banging noises and saying provocative things, according to Liberty. The cell isolated him from contact with other jail inmates, which allowed him to be under constant supervision and subject to 15-minute checks because his behavior was “challenging,” Liberty said.

“He had not assaulted anyone yet, but he was verbal and loud and uncooperative,” Liberty said after the death.

But two inmates said Thursday that Kitchin was ignored, despite his pleas for help. Michael Nickerson, 28, said he was brought into the jail between 1:30 a.m. and 2 a.m. Dec. 11 and was in the intake department for six to seven hours. The whole time he was there, Nickerson said, Kitchin was knocking on his cell door, asking to see emergency medical personnel and requesting that he be taken to the hospital because he did not feel good.

“They didn’t even acknowledge him,” Nickerson said. “Some of the guards said he always acts out when he’s here. They basically just ignored him.”

Nickerson, who was in jail on a probation hold, said when he saw the Kennebec Journal story saying Kitchin had died in a jail observation cell, he was stunned.

“I said, ‘Oh, my God — that was where that old man (Kitchin) was,'” he said.

Kevin Swift, 23, of Gardiner, who also was jailed there, said he saw and heard Kitchin banging on the door for at least six hours and corrections officers did nothing about it.

“They weren’t paying him no attention,” Swift said. “They were just sitting there.”

At one point, the jail nurse arrived and stood outside Kitchin’s cell and looked in but did not enter, according to Swift. “Obviously, he needed to go to the hospital,” he said.

Swift, who said he was in jail after having been arrested for violation of conditions of release and domestic violence, said that when he saw Kitchin again, he was dead.

“I saw them take him out on a stretcher,” he said.

Kitchin had been arrested two days before, on Dec. 10, by Waterville police and charged with criminal trespass after someone on Butler Court called police and said she did not want him at her apartment. He refused to leave and was arrested.

Waterville police had dealt with Kitchin about 50 times since 2006, according to police Chief Joseph Massey, for incidents involving criminal trespass, making a bonfire without a permit, shoplifting, theft and other offenses.

Steve McCausland, spokesman for the state Department of Public Safety, said after Kitchin’s death that state police investigate all inmates’ deaths and the state Department of Corrections also will review the incident. Liberty said an internal review also will be conducted by the jail.

Liberty said Friday he couldn’t comment on the specifics of the case, citing the incident investigations. But he noted that the observation cell is monitored 24 hours a day with 15-minute checks.

“If a request is made for medical attention, it’s referred to the medical staff. That’s standard,” Liberty said.

Waterville Police Chief Joseph Massey said police officers are trained to work with people who have mental health and other problems, and mental health workers ride with officers to try to help.

However, the situations can be challenging, because they often are dealing with people when they are not rational — and some are down and in the darkest moments of their lives, according to Massey. Police are trained to make referrals and contact other agencies to see if someone is available to help, he said.

‘AGONIZING PAIN’

Kitchin’s daughter, Danielle Kitchin, 37, said he suffered from health problems and was in “agonizing pain” the last couple of months because of his legs and one day took too many pain pills. She called crisis workers and 911, and he was taken to a local hospital and then to Alfond Center for Health in Augusta, where he was placed in a behavioral unit.

Five days later, he was released as being competent, according to both Danielle Kitchin and Kitchin’s niece, Lorna Hubbard.

Hubbard, 36, of Waterville, picked up her uncle at the hospital about two weeks ago and drove him back to the city, she said.

“He was still talking crazy. He went into the hospital because he tried to overdose. He took 10 pills. It was a pain med — Tramadol. He had blood clots in his legs — infection in both legs. It was bad.”

She said that on the ride home, Kitchin talked about missing toddler Ayla Reynolds, saying she was buried off Webb Road in Waterville.

“He was going to sue everybody,” she said. “He didn’t seem right. I just didn’t understand — I couldn’t even believe they let him out, acting like that. I didn’t understand why they didn’t keep him longer.”

Hubbard said Kitchin should have been kept in a hospital.

“His legs were blowing up and actually seeping infection out of him.”

Contacted by the Morning Sentinel, MaineGeneral Health issued a statement that it could not comment specifically on a patient. “Related to our policies and how we deal with patients, MaineGeneral adheres to state and federal laws,” it says.

Randy Moser, director of development and communications for Crisis & Counseling Centers, said Friday in an email that a mental health professional with the organization could not be reached immediately to comment generally about such situations.

Kitchin’s daughter, Danielle, said Kitchin was so generous that he would help a stranger who needed help. Her children didn’t have Christmas presents one year and he gave them $1,000.

“He was just a very giving man, always ready to help any way he knew. He gave the neighborhood kids ice cream and toys and he’d go to Ken-A-Set and buy clothes. He was not only a father to my children; he was a father to anybody that needed something extra.”

DeYoung, Kitchin’s sister, said he had a problem with drinking for many years and quit four months ago. He was taking Coumadin, a blood thinner, for the leg clots, and Tramadol for the leg pain.

“He was supposed to take two pills three times a day. He kept telling the doctor they didn’t work so he’d take more and he’d run out of them. He was like a schizophrenic.”

He started using foul language and became like a different person, DeYoung said.

“It wasn’t him. He was taking things that didn’t belong to him. He was doing things he’d never do. He’d go to the store and steal an ink pen. He would steal anything — stupid stuff, knickknacks and a shot glass.”

She said his legs hurt if he did not take his pills, and one time he crawled out of a hospital emergency room to go home when he was angry.

“The doctor told him to stay off his legs. He would walk the streets all night long.”

DANGER QUESTIONS

DeYoung said police and crisis workers said they could not put Kitchin in a hospital forcibly unless he was deemed an imminent danger to himself or others.

But he once left a frying pan on his brother-in-law’s stove, which started a fire in the kitchen, she said. “We were lucky that he didn’t burn their house down.”

Dana Kitchin grew up in Waterville, attended Waterville High School and dropped out and went into the Army, DeYoung said.

“He got through basic and all that, but he wouldn’t make his bed, so my father got him out on a hardship,” she recalled. “The military punished him by making him sleep in the woods. The whole squad would get punished for not behaving.”

Years later, he earned his general educational development certificate. He worked at Harris Baking Co. in Waterville and at Ralston Purina, a chicken plant in Winslow.

He was married for about 10 years, but the marriage dissolved; and afterward, he had a mental breakdown and was in VA Healthcare Systems-Togus, according to his sister, Joan Cuares, owner of PT Cab in Fairfield. She said when her brother was alive, all her cab drivers knew to pick him up if they saw him walking anywhere.

“He has been keeping the cops very busy. Three weeks ago he was in Fairfield, over by the Fire Department, and stole a pack of cigarettes and a candy bar out of a $30,000 car,” Cuares said.

Cuares said police knew he had troubles and tried to help him.

“They always treated Dana good,” she said. “I heard on the scanner one time, ‘How can you arrest a guy who says he loves me?’ It’s the system that sucks. There’s no way in hell they could have said he was competent. He was not fit to be on the street. He didn’t get the help, and we did everything. Crisis (and Counseling) did what they could. I think he was pushed through the system.”

A HIGH STANDARD

The law is clear about when someone with competency problems may be committed to a hospital: when one is a danger to oneself or others or has an inability to care for oneself, according to Karen Mosher, clinical director of Kennebec Behavioral Health.

“That’s a very high standard, and it has to be imminent,” Mosher said Friday.

Mosher said there is a huge number of people in the area who have co-occurring conditions — people who have multiple conditions that intensify a person’s problems, according to Mosher.

“You can have mental illness, substance abuse, chronic physical conditions, chronic social challenges, and the more of these situations that you pile up on top of each other, the more difficult it is for people to find a path out of it,” she said.

It also becomes more challenging for those who are trying to help them and keep them safe, she said. Kennebec Behavioral Health sees people with multiple conditions.

“There is much better behavioral and medical technology to treat people who have singular problems, so a lot of those folks are getting those needs met and treated because they’re part of a more specified system of care,” Mosher said. “A lot of people are taken care of by primary care physicians. That leaves us dealing with people who have more and more complex needs that are more and more difficult to treat.”

She said the state has been involved in helping emergency rooms to address people’s multiple needs.

The provider community meets monthly, and one of the goals is to share resources of expertise and discuss how best to manage certain situations, according to Mosher. She said they don’t discuss names but talk about a best approach to helping people.

“I think that there are some opportunities that are pretty cool in this region, and I think there are a probably a lot of people that fall through the cracks.”

Mosher said she feels sympathy for Kitchin’s family.

“It’s sad for the jail, too, because they really work incredibly hard to take good care of people who have co-occurring disorders,” she said. “Sheriff Liberty is very, very sensitive to that issue. He really does a lot of innovative work around it, and I’m sure this is incredibly painful. I have tremendous admiration and respect for the work that he’s doing.”

Amy Calder — 861-9247

Twitter: @AmyCalder17

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.