We grow up being taught to look before we leap and think before we act, especially in dangerous situations. In its booklet on dealing with “active shooters,” the Department of Homeland Security lists confrontation as the “last resort,” after, among other things, taking note of the nearest exits and locking yourself in an office. Police tell us not to confront someone “armed and dangerous.” And our spouses and other loved ones tell us, “don’t be a hero.”

Yet it turns out, according to a recent study of why people take extreme risks to save lives that are at immediate risk, that the ones who do indeed come to the rescue, like the three Americans on that French train, are those who completely disregard all that advice.

If you stop to contemplate whether to act when the danger actually confronts you, you probably won’t, the study suggests.

And the answer to the the question “what were they thinking when they risked their lives?” is that they weren’t thinking, at least not very much. They just did it. If you think about it too much, you won’t.

Yale scholar David Rand called it the “danger of deliberation” in an interview with The Washington Post, and it appears to be the biggest deterrent to what he calls “extreme altruism.”

That’s the essential finding of Rand’s study with co-author Zev G. Epstein of Pomona College, “Risking Your Life without a Second Thought: Intuitive Decision-Making and Extreme Altruism.”

The study does not take issue with such warnings, urge any course of action or pass moral judgment.

It seeks to answer the questions people ponder after news stories like the one that broke over the weekend, that three American friends helped foil what could have been a mass shooting on a packed high-speed train bound for Paris. They arise too, when people don’t act, as in July, when no one among the dozens in a Metrorail car in Washington took action to stop a knife-wielding man who punched Kevin Joseph Sutherland to the floor and stabbed him 30 or 40 times until he was dead.

Social scientists and neuroscientists have been asking the same question ever since news reports, which turned out to be greatly exaggerated, about how no one ran to the aid of a bar manager named Kitty Genovese in March 1964 in Queens when she was murdered by a computer punch card operator.

But the answers provided by academia have been unsatisfying. For one thing, there’s no ethical way to conduct true-to-life lab experiments in which students can be observed responding, or not, to someone in the group getting stabbed, shot or beaten. And people who don’t help tend to be understandably reluctant to subject themselves to the public shaming that accompanies the admission that they did nothing while someone died in plain sight.

But heroes do talk, if they survive. And in their study last year of Carnegie Hero Medal Recipients — people who pulled others from fires, broke up violent crimes or dove into perilous waters to save a life — Rand and Epstein’s answers were deeply revealing, albeit blindingly obvious if we listen to, and take seriously, what such heroes invariably tend to say in the wake of their heroism, instead of writing off the words as a show of modesty.

Here’s what some of the study’s respondents, not identified in the research, said when asked about their particular feats of courage:

“Honestly, in a situation like that. . . . You don’t think. . . . You just react. I just reacted. He had to be stopped.”

“I didn’t think about it. I didn’t have time to think about it. It just happened. . . . It was instinct. I just think it was the adrenalin that pushed me to do that.”

“The minute we realized there was a car on the tracks, and we heard the train whistle, there was really no time to think, to process it. . . . I just reacted. I think when we’re forced into this kind of situation you become a different person.”

“I went ahead and just climbed through the fence and I don’t remember ever feeling the electricity. . . . If nobody came to this woman’s rescue, she would die. I didn’t really take the time to think about what would happen.”

‘I JUST DID IT’

The Carnegie heroes come from all walks of life. Some have been trained as first responders. Most have not. What they “had in common,” said Rand in an interview, “was their style of thinking. They were almost all people who in their particular situation went with their guts. ‘I didn’t think about it. I just did it.’ There weren’t people who said ‘I was scared. I’m going to make myself do it.’ That kind of person is not going to act.”

In effect, he said, it’s their “default” position when one of these “extreme” high-stakes events happens.

They weren’t spending time in the face of a threat calculating the merits, and the costs and benefits, of whether to act or not. They just did it. These practitioners of “high-stakes extreme altruism” may have been “largely motivated by automatic intuitive processes,” write Rand and Epstein.

“The people that actually act,” Rand told The Washington Post, “are the people that both have a sort of cooperative impulse and are people who don’t overthink things.” It’s “the kind of thing that if you stop and think about it, you start coming up with reasons why you shouldn’t act. The danger of deliberation is that it is dangerous and if you stop to think it’s going to be in your self interest not to act. When you start thinking about it, you can rationalize. ‘Oh if I tried to act nobody else would.’ Or, ‘if I tried to act, it wouldn’t work.’ You can come up” with all sorts of reasons. “It’s a weird thing. I spend all this time researching this stuff . . . and come up with this conclusion that it’s the people who go with their gut.”

“These results,” said the study, “suggest that the decision-making processes described by the CHMRs [medal winners] were predominantly driven by intuitive, fast processing.”

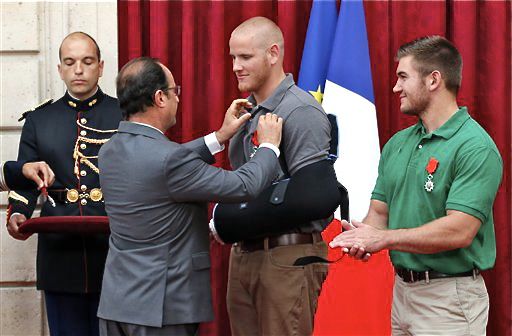

The story of Anthony Sadler, Airman 1st Class Spencer Stone and Spec. Alek Skarlatos sounds like it came straight off the pages of Rand and Epstein’s study. As The Washington Post’s Michael Birnbaum wrote, Stone was in “the middle of a deep sleep” when he heard the initial scuffle between the shooter and the French citizen who was the first to stumble on him, he said. But then his friend, Spec. Alek Skarlatos, 22, and recently returned from a deployment in Afghanistan, “just hit me on the shoulder and said ‘Go,'” Stone said.

There was no time to plan, they said, no time even to think.

“We just kind of acted. There wasn’t much thinking going on,” Skarlatos said. “At least on my end.”

“I mean, adrenaline mostly just takes over,” Skarlatos told the New York Times when asked why he rushed forward. “I didn’t realize, or fully comprehend, what was going on. In the beginning it was mostly gut instinct, survival,” he told reporters later. Sure, some of them were trained servicemen. But, he added, “Our training kicked in after the struggle” began, not at the point where they lunged forward to act.

Other heroes have described their reaction in similar language. “It was a human reaction,” said Lenny Skutnick, perhaps Washington’s most fabled extreme hero, who jumped into an icy Potomac to rescue victims of the 1982 Air Florida plane that crashed into the 14th St. Bridge. Diving into an icy river at twilight, said Skutnik, “was a human reaction, like breathing, like walking.”

Roger Olian, who jumped in to help rescue a woman that night was more vivid when asked what got into him. “It was like a bolt of lightning or something hit me,” he said years later. He just told himself, “You’ve got to go get her.”

“Kind of an instinct” was the phrase Dylan Rawls used to describe his much more recent act of bravery. At 1:15 on a Sunday morning last April, five men who had consumed too much alcohol began beating another at a parking garage on St. Elmo Ave., in Bethesda, Maryland, until he was unconscious and, even then, one of them continued stomping the victim, apparently intent, as the conviction would ultimately confirm, on killing the man. We know about the beating in part because there were a number of bystanders who, instead of stepping in to help, took cellphone video, described at the time as too brutal to air in public.

But not Rawls, who on his way home early that morning, intervened and, prosecutors say, saved the man’s life. What was he thinking? Rawls was later asked. The answer? He wasn’t. He “just jumped in.”

WHY MANY FAIL TO ACT

What of those who don’t act? Anecdotally at least, to the extent they have publicly explained their inaction, their words seem to confirm the “danger of deliberation” theory put forward by Rand and Epstein.

In one highly publicized incident in July bystanders reportedly did nothing as an assailant on a Metrorail car punched and stabbed Kevin Joseph Sutherland 30 or 40 times until he was dead. Instead, as police reported at the time, people “huddled at both ends of the car and watched in horror,” taking no action. One woman, who agreed to be interviewed by The Post on condition of anonymity, said she and the others thought about getting involved but “told one another that it was too dangerous to intervene. ‘I think we were all trying to stay away from him considering he had a knife,'” she said. “‘People who were in front of us were saying, ‘Don’t do that.’ ”

“The 52-year-old woman,” reported The Washington Post, “said she was terrified.” “I would have to say that my instinct was to stay put and try to become as small as possible,” she said. “I’m looking, but I don’t want to be noticed by him.”

Neither Rand, in the interview, nor the study, attempts to cast moral judgment on those who don’t act or urge some reckless course of action on the general public. Instead he only seeks to help explain what motivates those who do act.

Rand says he does believe that “you can cultivate a willingness to act.” But at this point, he said, “we don’t have a handle on how best to do that.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.