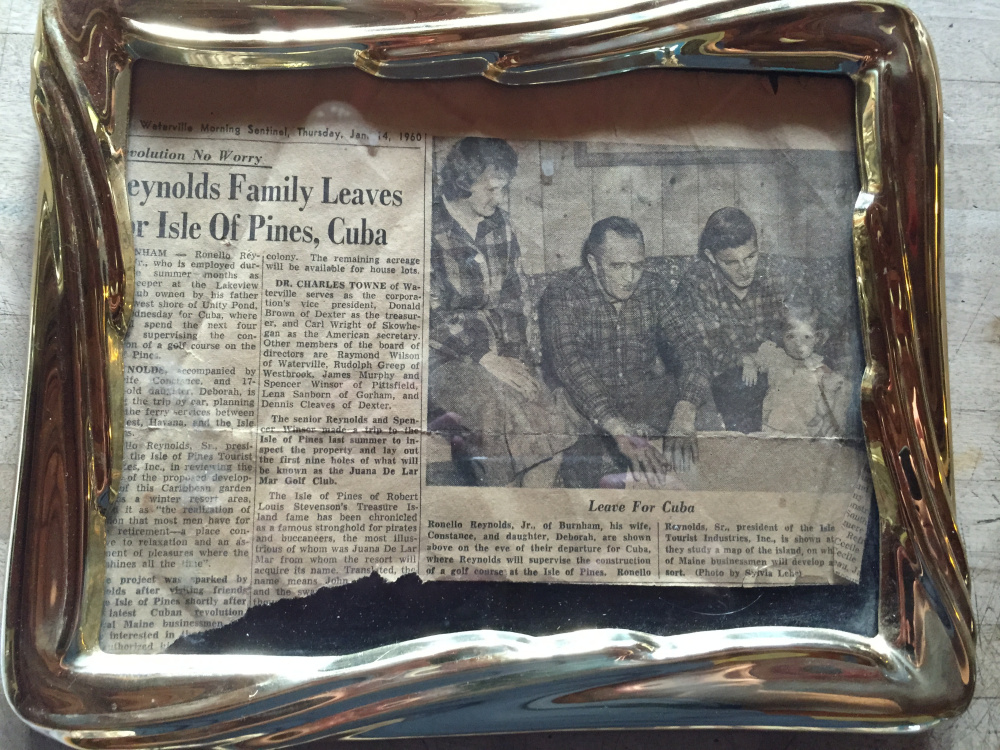

The newspaper clipping is yellow and ragged, even after years in a frame. The story — from the Morning Sentinel edition of Jan. 14, 1960 — tells of Ronello Reynolds Jr., who is about to embark on a huge adventure with his family from Burnham, Maine.

With his young, pregnant wife, Constance, and toddler daughter Debby, Reynolds — known by the nickname Brother — was preparing to go to Isle of Pines, Cuba, where he’d supervise the building of a golf course. That would become the centerpiece of a resort.

The golf course was the brainchild of Reynolds’ father, Ronello Reynolds Sr., who saw the project as a destination for Americans looking to hide from winter. In a photo accompanying the story, Ronello Sr. and Jr. look over maps of the land on which they will build their golf course. Constance and Debbie look, too.

With 55 years of hindsight, three words above the story’s headline provide ominous foreshadowing.

“Revolution No Worry,” it reads.

• • •

Ronello Sr. died in the mid-1980s and Brother died in May this year.

In recent weeks, the tensions that hung over the United States-Cuba relationship for more than half a century have eased. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry was recently in Havana for the reopening of the U.S. Embassy.

Now, the surviving members of the Reynolds family have wondered: What happened to that land?

Debbie Berry, the toddler in 1960, who now lives in Auburn, said she might someday travel there to try and find out.

“I always wondered,” Berry said. “It felt like it was a little part of mine. I’ve always wanted to go back.”

Tammy George, Berry’s younger sister, who still lives in Burnham, said she heard it was made into an airstrip, “but we don’t know. We were never allowed back.”

George was born after the family’s Cuban adventure was over, but she grew up hearing the stories. She’s seen the pictures. She and her husband, Steve George, now run Lakeview Golf Course, the course built by Ronello Reynolds Sr. on the shores of Unity Pond in 1927.

The Isle of Pines golf resort, Juan De Lar Mar Golf Course, was never completed, of course. Months after they left Burnham, Reynolds Jr. and his family were back in the United States. The golf course and accompanying land was lost to the Cuban embargo.

In his June 19, 1960, president’s report to the shareholders of Isle of Pines Tourist Industries Inc. — the company formed in 1959 to oversee the resort — Ronello Reynolds Sr. was confident construction of the golf course would continue after a brief delay.

“I sincerely believe that Cuban-American relations will improve and it is to our advantage to preserve our privileged status quo for the time being, while relations between the two countries remains strained,” Reynolds Sr. wrote.

Constance Reynolds said when she and her family were on Isle of Pines, there was no electricity, so news of what was happening on the main island was hard to come by. The property on which they lived was guarded by revolutionary soldiers. At most, the soldiers would occasionally get drunk and fire their machine guns into the air. Reynolds said she and her family never feared for their safety while in Cuba.

Roy Fall had worked at Lakeview Golf Course since he was 12. Nineteen years old in 1960, Fall was hired to go with Brother to Cuba and work on clearing the land that would become the golf course. Young and single, Fall often would go into town at night and drink with the soldiers.

“Nobody ever bothered us,” Fall said.

When they were told they had to pack up and come home, it came as a bit of a surprise.

“We didn’t know until we got off the island how bad it was,” Constance Reynolds said. “The truth seeped in. We can’t go back.”

• • •

Ronello Reynolds Sr. was, as his family describes him, a man ahead of his time.

“My grandfather was always into some new adventure,” said Debbie Berry, the toddler in Cuba. “He just liked to live life. He was a phenomenal storyteller. My grandfather talked about how much he loved the (Cuban) people and the music.”

As a boy, Reynolds worked on the family’s Burnham farm. He harvested ice from Unity Pond, which was kept cool in the barn, covered in hay, all summer. He tried to save his father, Wilbur Reynolds, after a vicious goring from a bull.

The elder Reynolds was a fun-loving traveler who rarely sat still. When Ronello Jr. was born, Reynolds was about to start a round of golf. When somebody yelled from the house, “You’ve got a son!” Reynolds nodded, teed off, and played nine holes.

Constance Reynolds, his daughter-in-law, recalls Reynolds driving around town in his Cadillac convertible, a bear he had shot hunting sitting alongside him in the front seat. Reynolds looked for adventure, and that was how he found a spot on the north side of Isle of Pines that he knew would be the perfect place for a golf course.

According to that Morning Sentinel story from 1960, a visit Reynolds made to friends on the Isle of Pines shortly after the Cuban Revolution began sparked the idea for a golf resort on the island.

Isle of Pines is about 30 miles off the southern side of Cuba’s main island, near the western edge. Just 850 square miles, the island was renamed Isla de la Juventud (Isle of Youth) in 1978. From 1953 to 1955, Fidel Castro was imprisoned by Cuban president Fulgencio Batista in the island’s Presido Modelo.

Isle of Pines was already a tourist destination when Reynolds Sr. hatched his plans for a resort, with much land already owned by Americans.

“My father-in-law was quite a wheeler-dealer. He was always into something,” Constance Reynolds said. “He drummed up investors to buy the property.”

In early 1959, Reynolds Sr. put together a group of investors from central Maine, including Charles Towne, of Waterville; Carl Wright, of Pittsfield; and Donald Brown, of Dexter. On June 19, 1959, paperwork was filed in Somerset County, and Isle of Pines Tourist Industries Inc. was created.

Reynolds was president. Towne was vice-president. The secretary was Guillermo Hodge Morales y Patino, a lawyer who lived on Isle of Pines. Wright served as assistant secretary, and Brown was the corporation’s treasurer. According to the document filed that day in Skowhegan, the company was dedicated to the construction of one or more golf courses “designed to attract quality tourists to Cuba’s hospitable shores in greater numbers all year around.”

Work was to begin on Nov. 1, 1959, but that start date proved to be politically unfeasible. Tension between the United States and Cuba was too high, and that seemed to frustrate Reynolds Sr., who addressed the problem in his president’s report in 1960.

“At one moment American officials in high office announced that travel to Cuba by Americans might be soon banned. In the meantime, the Cuban Tourist Commission proceeded with its promotional plans and it was commonplace to see on one page of a metropolitan newspaper beautiful advertisements of Cuban tourist attractions — while on another page there appeared fear headlines and disconcerting news reports predicting that American tourists would be greeted by machine gun fire,” Reynolds wrote.

• • •

In Cuba, Debbie the toddler was a superstar. She was the only blue-eyed blonde the locals had ever seen. In high school, Berry would tell her friends that she had been to Cuba. Nobody ever believed her.

In the Reynolds family photo album, there’s a picture of Debbie and her parents sitting with four soldiers. One is playing a guitar, and one is holding Debbie and grinning ear to ear. Perhaps he is the soldier Debbie was told walked into town twice a week to get her treats.

“I was like a celebrity down there,” Berry said. “I was told it was a good experience.”

Pregnant the entire time she was in Cuba, Constance Reynolds felt sick most of the time she was there. Still, she enjoyed the time.

“It was a real friendly country,” she said.

While blond Debbie was a celebrity and Constance fought sickness, Brother and Fall worked. In the short time they were on Isle of Pines, the pair, along with a small crew of local workers, accomplished quite a bit.

They surveyed the property, cut and cleared obstructions to the golf course. They hired a road grader, plowing, leveling and sculpting the land into something resembling a golf course.

It was here that Morales, the lawyer who had the most shares in Isle of Pines Tourist Industries Inc., earned his money. When a grass fire Brother and Fall started in the land-clearing process burned out of control, the duo faced serious charges.

“(Morales) kept us out of jail,” Fall said. “We had a pig roast at his house. He probably thought we were going big-time.”

In his president’s report, Reynolds Sr. noted all the work completed in just four months, with a minimum of three men working for at least three of those months.

“The total cost, including all labor, gasoline, and materials amounts to $4,002,” Reynolds Sr. wrote. “This sum includes the round trip transportation of two men familiar with this work, from here to the Isle of Pines.”

Reynolds Sr. noted that costs were able to be kept low in part because of the generosity and cooperation of locals toward the project. The road grader, for instance, normally would have been a $25 per day rental. Brother and Fall were allowed to use it free, and with a $1.50 per hour fee for the operator.

Nine holes of the course needed to be seeded, but the project was moving along well. Reynolds Sr. closed his report with optimism for the next phase, which was to include a bar, pro shop, marble patio, caddie house, irrigation system and maintenance machinery. He included an estimate of the price.

“The amount is approximately $15,000, and the time required is at least 6 months,” Reynolds Sr. wrote.

• • •

They didn’t have six months. Relations between the United States and Fidel Castro’s Cuban regime fell apart quickly, and Americans in Cuba were told they had to come home.

“We were told, ‘You’ve got to leave. The boat is leaving,'” Constance Reynolds said. “So we put the car on the ferry and left. We were lucky to get out. We were lucky to get home.”

“We left when we were told nobody could guarantee the ferry would run from Havana to Key West,” Fall said.

As quickly as that, Reynolds Sr.’s dream of a resort that would attract tourists from around the world to play on a golf course surrounded by the Isle of Pines’ black sand beaches was gone. America placed an embargo against Cuba and ties between the two countries were severed.

But with relations between the U.S. and Cuba now thawing, Debbie Berry hopes she can go back someday and see what became of Juan De Lar Mar Golf Course. Was it made into an airstrip? Did the land Brother and Fall cleared for fairways and greens become overgrown again? Were uprooted palm trees replaced by new ones?

Fall, now 74, also would like to know what happened to the land of Isle of Pines.

“I’d rather go to that island than Havana,” Fall said. “That island was nice. The people were nice.”

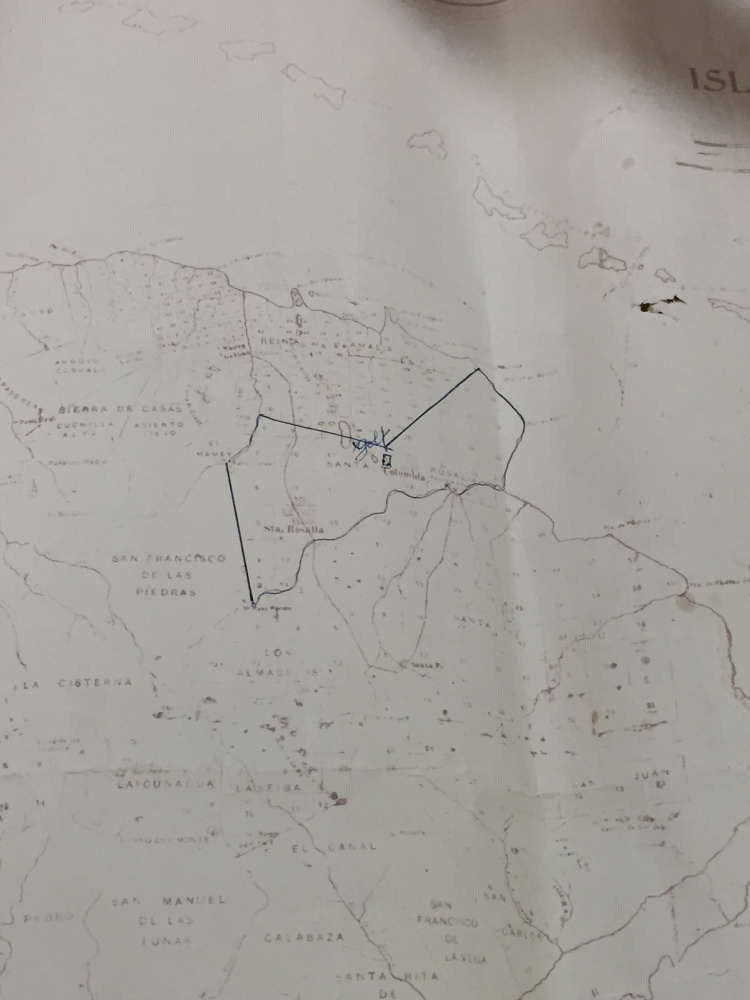

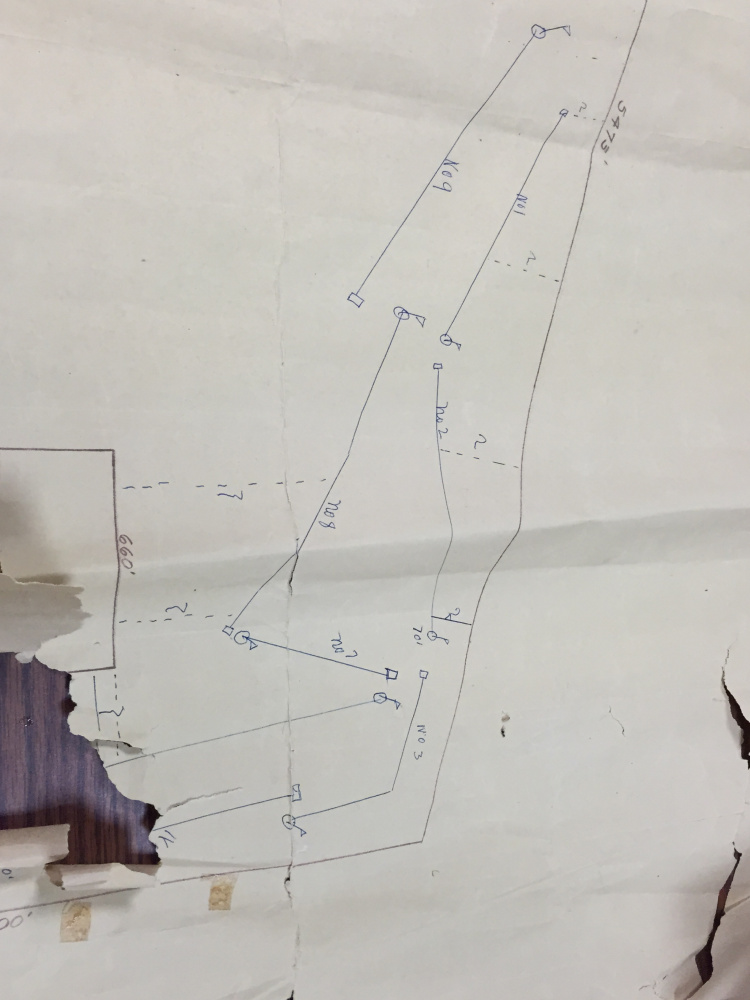

Recently, Tammy George found two maps. One, of Isle of Pines, shows the outline of what would have become the resort on the north side of the island. The other is a crude outline of a nine-hole golf course.

Hole three would have had a challenging dog leg.

“My sisters and my own children have done research,” George said. Her daughter, Katie George, did a research project on the Cuban golf resort as a student at Maine Central Institute in Pittsfield. “We always meant to write everything down, but you know how that goes.”

Life goes on, and after a while, plans for a luxury resort are reduced to a yellow, 55-year old newspaper clipping.

Travis Lazarczyk — 861-9242

Twitter: @TLazarczykMTM

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.