FARMINGTON — Amid the dust, dump trucks and construction clatter, a vision of a sustainable future is being brought into reality on the University of Maine at Farmington campus.

On a former parking lot tucked into the back of campus is the key to UMF’s path to becoming the state’s first public institution of higher education to heat its campus almost entirely with a sustainable energy resource in the form of a biomass central heating plant.

“This biomass plant offers a very important milestone in our renewable and sustainable energy journey on the UMF campus,” Luke Kellett, coordinator of UMF’s Sustainable Campus Coalition, said.

The $11 million biomass heating project, which was approved last January, broke ground in June and is halfway to completion. When it’s done, it will replace oil as the campus’ primary energy source. The project is also a step toward the university’s goal to be carbon neutral by 2035.

The project was proposed after Summit Natural Gas plans to extend a pipeline to Farmington were delayed until 2016. University officials were not content putting off their commitment to sustainability any longer.

“Even from the early stages, (the project) was going to be a natural gas plant with the hope to be biomass at some point later in the future. But because of natural gas backing out, we jumped ahead to go right to biomass,” said Jeff McKay, director of facilities management at UMF.

OUT WITH THE OLD

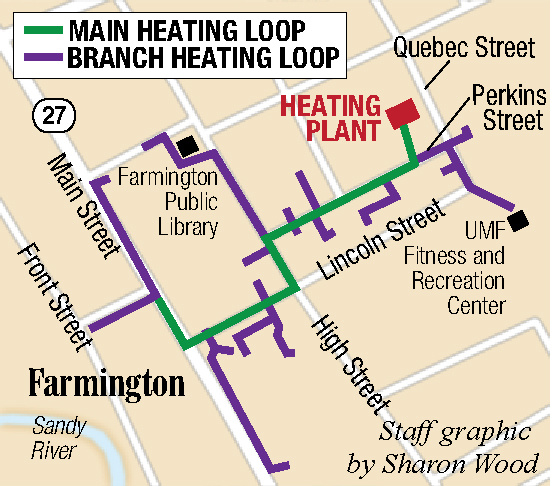

The 5,885-square-foot central heating plant being built on the corner of Perkins and Quebec streets will house the biomass heating boiler. The boiler will burn 4,000 tons of locally sourced wood chips a year to heat water circulating through two miles of underground piping connecting campus buildings to the plant.

McKay says that the loop is about 80 percent complete and will be heating the campus by mid-November using the existing oil boilers on campus. Over winter break the biomass boilers are expected to be fired up, and by the time the students return, the biomass system will be completely up and running.

Aside from the construction of the heating plant itself and the extensive trench work that has been underway on campus to install the two miles of steel piping that makes up the heating loop, UMF facilities management workers and contracted Vining Construction crews have to replace the large oil furnaces with smaller biomass heat-exchangers in the basements of campus buildings.

“This project is so long and intrusive, and that has been one of the biggest challenges — working around the academic calender,” McKay said. “It’s intrusive. However, it is a very, very good project. So the short term discomfort hopefully is going to be outweighed by the long term gain.”

Similar biomass heating systems are being used by Colby College in Waterville and the University of Maine at Fort Kent.

The biomass system in place at Colby since 2012 is larger than the UMF project, but is using steam instead of hot water. It was funded privately by the college. The $2.6 million Fort Kent biomass system was constructed in conjunction with the Fort Kent Community High School campus through a U.S. Department of Agriculture grant and is “about half the size of our heating system, maybe even less than that,” McKay said.

The UMF heating plant is projected to recoup construction costs through financial energy savings in the first 10 years of operation, replacing 390,000 gallons of heating oil that is now being used annually to heat 95 percent of the buildings on campus. Overall the conversion to biomass will decrease UMF’s carbon emissions by 3,000 tons a year, Kellett said.

Once the new heating plant is in full operation, 95 percent of the campus will be heated by renewable biomass. Four fuel-efficient oil boilers will remain in operation on campus to add heat to the loop and serve as a backup source of heat if the biomass system ever goes off line.

“Most of the heat is going to come from (the biomass plant) to heat that water, but there are a few what-they-call ‘injection points’ at these four buildings on campus, where heat is going to be added to the loop,” Kellett said. “It’s also a good back up to keep just a small amount of oil in case this ever did go off-line. We need some degree of a backup, just in case.”

VISION FOR A SUSTAINABLE CAMPUS

The central heating plant is the largest step UMF has taken towards reducing its carbon footprint, but it is not the first.

Around 2000, UMF officials began to think critically about the future of campus sustainability and what steps they could be taking as a university to reduce their carbon emissions in order to combat climate change, Kellett said. In the following years, the school began investing in geothermal energy and has installed 142 thermal wells on campus, as well as converting buildings to meet certifiable LEED standards.

In 2010, UMF drafted a Climate Action Plan that lays out the university’s goals for reducing carbon emissions. Kellett said that for many years the UMF campus has emitted around 12,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide annually, though reports show that a slight decline in emissions began in 2007. The Climate Action Plan sets a goal of reaching carbon neutrality by 2045 with an intermediate 2025 goal of a 43-percent reduction in emissions from 2007 levels.

In 2014, Kellett said that UMF emitted about 10,800 metric tons of carbon, but that the campus conversion to biomass will reduce current emission levels by 3,000 to 4,000 metric tons. Projections show that with the biomass heating system in place, the campus’ carbon emissions will hover around 7,000 metric tons, putting UMF on target 10 years ahead of schedule to reach its 2025 goal, Kellett said.

“Ultimately we hope to drastically alter the campus energy mix away from fossil fuel to renewable sources. This heating plant guarantees that energy shift and highlights the sustainability commitment that UMF continues to embrace,” Kellett said

The next step UMF hopes to take is to explore how wind and solar power could be incorporated into their energy portfolio.

STATEWIDE CARBON REDUCTION

In September, the University of Maine System board of trustees released a press release stating as a system Maine’s universities had achieved a 26-percent reduction in carbon emissions since 2006. As part of its Energy and Sustainability Report, the system also announced that campus dependence on heating oil is expected to drop by an estimated half-a-million gallons by the start of 2016.

“Maine’s universities are leaders on the environment because of our research and our programs, our investments and the daily choices we make across our campuses,” UMS Chancellor James H. Page said in the release.

The UMF biomass conversion accounts for 80 percent of the half-million-gallon reduction that is occurring in the seven UMS campuses. Other carbon reducing projects across the system include a compressed natural gas project replacing 13 boilers at UM Machias, three newly installed natural gas boilers on the University of Southern Maine’s campus and the biomass heating system at UMFK.

In January, the board of trustees voted to begin divesting its direct holdings in coal companies, making UMaine the first public land and sea grant university in the nation to begin divesting fossil fuels.

The moves toward sustainability taken by UMS over the last year are being fueled by the idea that the system wants to set an example of environmental stewardship for the students it is educating, said Dan Demeritt, executive director of public affairs for UMS.

“We are working hard to be responsible stewards of the tax and tuition dollars entrusted to the university system and of the environment,” said Norman Fournier, chairman of the board of trustees Finance, Facilities and Technology Committee, in the release.

HOLISTIC VISION

The UMF biomass plant is already being incorporated into the curriculum across disciplines, Kellett said, and with the completion of the project by the end of the year and the inclusion of a classroom in the building, he expects the system as a learning tool for students to increase.

But inclusion in curriculum is only one way UMF is trying to convey a message of sustainability to its students and the surrounding community. As a group, the Sustainable Campus Coalition is made up of UMF faculty, staff, students and interested community members. The group encourages anyone with an interest in the environment or climate change to get involved regardless of their academic background.

In essence, the coalition allows any UMF student to get involved with projects like the biomass heating plant and learn firsthand what it takes to enact environmentally healthful projects and policies, said UMF alumnus Paul Santamore, who worked with the coalition when the biomass discussion first began.

“The holistic nature is something that is fostered at UMF and is something that is embraced. If you don’t know the technical terms, then someone will teach them to you or teach you how to understand the science,” Santamore said. “Farmington does a really nice job of integrating their visions, their values not only into actions, but into their curriculum and what they teach.”

Santamore graduated from UMF in May 2014 with an individualized study degree focusing on poverty policy. In his senior year, Santamore worked as a project assistant for the coalition leading meetings and helping work on the sustainability plan. While Santamore was not a science student, the coalition allowed him to work closely on issues he was passionate about and to have a say in the direction of UMF’s sustainability future.

Kellett says that the coalition encourages student input and hosts energy forums to gauge student attitudes toward sustainability ideas.

Santamore recalls that during his time on the coalition, students were concerned about the initial natural gas project for ethical and political reasons, but also because they felt the idea of a natural gas pipeline didn’t fit in with UMF.

“The biggest opposition we had with natural gas, other than some ethical worries that the students had, was that UMF was taking the same step as everyone else,” Santamore said. “We weren’t being innovative and we weren’t being different, which is what Farmington is about. It’s a very different place.

“And with Farmington taking that innovative role in the green functions of a University by converting (to biomass) or being more sustainable or using local food and having an active student group, I think that’s huge.”

Lauren Abbate — 861-9252

Twitter: @Lauren_M_Abbate

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.