Howard Marks, a Welsh-born, Oxford-trained drug smuggler who for years ran a globe-spanning marijuana ring, enraging officials and entertaining the public on both sides of the Atlantic as a countercultural scofflaw, died April 10. He was 70.

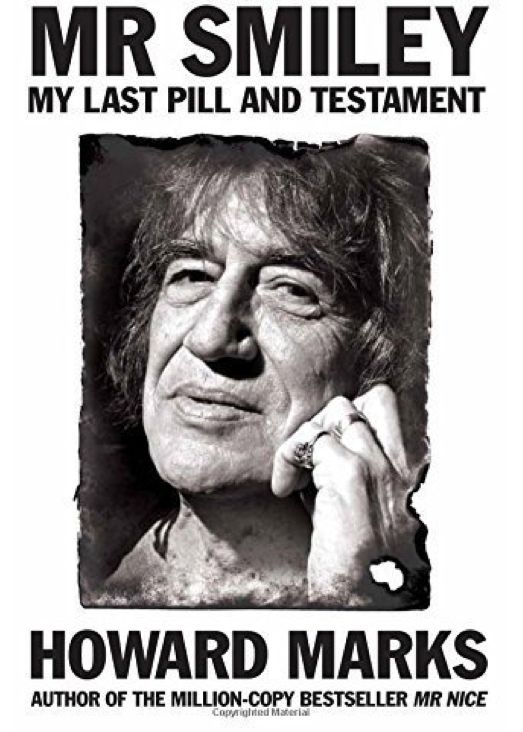

Marks revealed last year that he had inoperable bowel cancer, and his death was announced by Pan Macmillan, the publisher of his most recent book, “Mr. Smiley: My Last Pill and Testament” (2015). Other details were not immediately available.

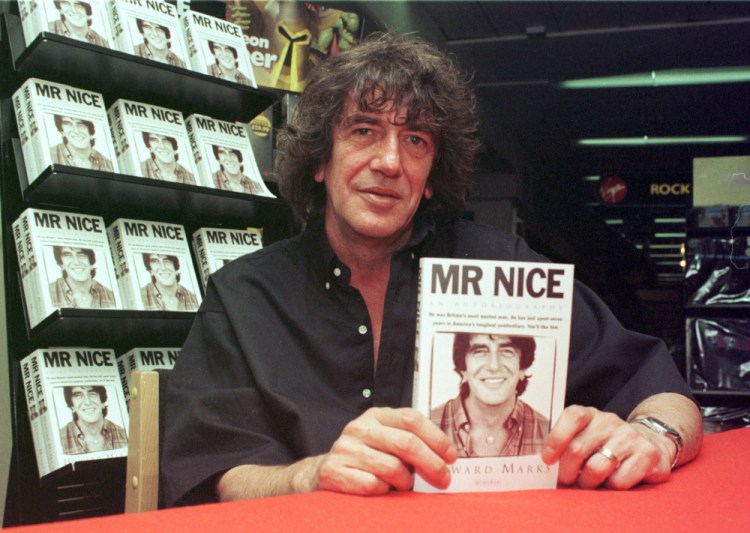

Once described as “sounding like Richard Burton and looking like a Rolling Stone,” Marks achieved celebrity and notoriety in a life that took him from a mining village to the University of Oxford, to prison, and finally to bestsellerdom with the release of his memoir “Mr. Nice” (1996).

“He was a product of the 1960s, a proletarian boy who shot into the heart of the British establishment and proceeded to laugh at it,” David Leigh, a former investigations editor at the London Guardian and a biographer of Marks, said in an interview. “He had this kind of anarchic spirit and this beguiling smile and this recklessness that appealed to a lot of people. It makes some people in Britain very indignant when you say that.”

An official with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration labeled Marks the “Marco Polo of the dope world” – others dubbed him “Narco Polo” – and he served seven years at a federal penitentiary after pleading guilty to racketeering charges in a Florida court in 1990.

According to the indictment, Marks and his associates had smuggled thousands of tons of marijuana and hashish into the United States and Canada through a criminal organization that had operated since 1970, reaching into Britain, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Singapore, Australia, West Germany, the Philippines, Thailand, Pakistan and Hong Kong.

Years earlier, he was acquitted on drug charges in England after claiming he was in the service of the British intelligence agency MI6 and Mexican authorities pursuing drug dealers. At least once during the proceedings, his lawyer reportedly struggled to muffle his own laughter.

The courtroom coup helped burnish Marks’s image in some circles as a folk hero, a reputation he established in the 1970s after he was arrested in Amsterdam and went on the lam. He lived under a reported 43 aliases, among them “Donald Nice.” Britons delighted in Howard Marks sightings.

“I was a fugitive for six-and-a-half years, and I smuggled as much cannabis as I could,” he once boasted, according to his obituary in the Guardian. “I felt that this was my destiny, this was my karma. I suppose I felt like a prizefighter. One day one’s going to get knocked out on the canvas. You have to carry on until you’re beaten.”

By his account, Marks availed himself abundantly of the products he sold: He claimed that he had smoked hashish every day for 22 years, according to the Daily Telegraph.

He did not engage in the traffic of harder drugs, a decision attributed to his grief over the loss of Joshua Macmillan, a friend at Oxford and grandson of former British prime minister Harold Macmillan who died after becoming addicted to heroin and cocaine.

After his release from U.S. prison, Mr. Marks published his autobiography – the title, “Mr. Nice,” referred to his alias – which became a juggernaut around the world. He detailed the trade that he said touched on the CIA, the Irish Republican Army and the mafia.

Reviewing the volume in the London Independent, the British writer Duncan Fallowell observed that Marks’ memoir, which became a movie starring Rhys Ifans, existed in “a conspiratorial society, that is, in the realm of flexi-truth.”

“In such societies nobody knows what’s really going on most of the time, and very often the more you investigate, the less certain you become,” Fallowell wrote. “In other words, Mr. Marks’ version is as true as anyone else’s.”

Mr. Marks wrote several other books, among them a sequel to his memoir, “Señor Nice: Straight Life From Wales to South America,” and a novel. He also appeared in a one-man show and wrote for British newspapers, advocating greater acceptance of marijuana.

“Of course the legalizing of marijuana for medical purposes is to be welcomed,” he told the Observer after his cancer was diagnosed, “but personally I never wanted to have to wait until I had cancer before I could legally smoke.”

Dennis Howard Marks was born in Kenfig Hill, a working-class community in South Wales, on Aug. 13, 1945. His father was a merchant sailor, and his mother was a teacher.

A scholarship allowed Marks to study physics at Balliol College, where he graduated in 1967, and where he learned that he could make money selling cannabis. He ran a boutique, Annabelinda, which ostensibly sold clothing but in fact peddled marijuana. He said that he came into contact with smugglers, and “from there I became a smuggler myself.”

His marriages to Ilze Kadegis and to Judy Lane, who was imprisoned for a period with Marks, ended in divorce. His survivors, according to the Guardian, include three children from his second marriage, Amber, Francesca and Patrick, and a daughter, Myfanwy, from an earlier relationship with Rosie Lewis.

Most of Marks’ considerable wealth was consumed by his expensive tastes and legal fees or confiscated by authorities. In the late 1990s, with his extensive background in the relevant subject matter, he applied for the position of drug czar under Prime Minister Tony Blair.

“I am sorry to inform you that we were unable to include you in the candidates invited for interview,” he was told in a reply. “I hope that your disappointment will not prevent you from applying for other positions we may advertise in the future.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.