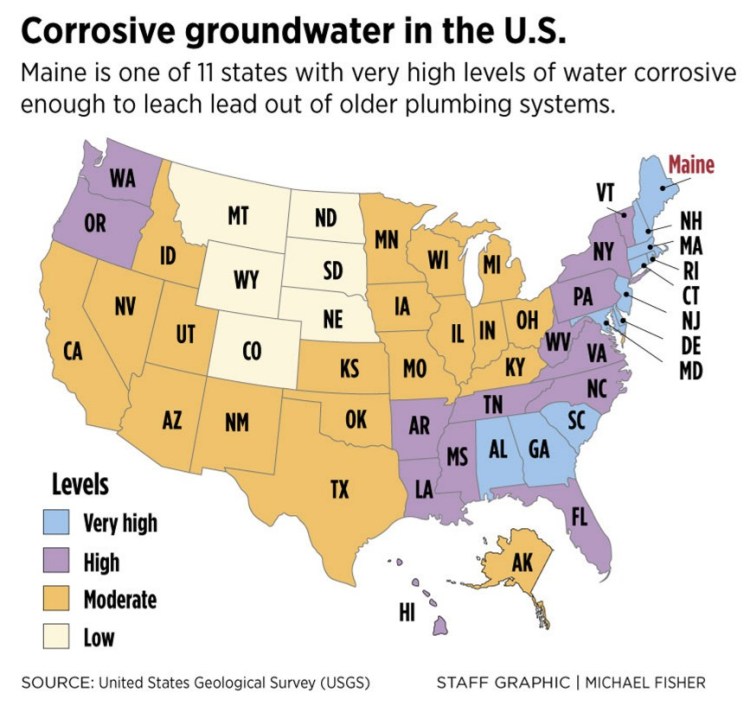

Maine is one of 11 states with a “very high prevalence” of groundwater potentially corrosive enough to cause metals such as lead to leach out of household plumbing, according to a new federal report.

The finding highlights the importance of water testing for homeowners, especially those on private wells. In Maine, that’s about half of the total population.

In a national study of roughly 27,000 untreated groundwater sources nationwide, the U.S. Geological Survey found that 25 states plus the District of Columbia had “high” or “very high” rates of potentially corrosive groundwater. The issue was most acute in the coastal states from Maryland to New England, where five of its six states had a “very high” potential for corrosive water that – although naturally occurring – could cause lead contamination problems for older homes on private wells.

Roughly 8 million people – including an estimated 561,000 Maine residents – use private wells rather than public water supplies in the 11 states with a “very high prevalence” of corrosive water. Although the report makes no recommendations, USGS scientists said the findings could be used in policy discussions or influence homeowners’ decisions about whether to test their water or install treatment systems.

Mike Beliveau, executive director of the Portland-based Environmental Health Strategy Center, said the study results should serve as a call to action in Augusta.

“We need legislative action to guarantee safe and affordable drinking water to everyone,” Beliveau said. “Maine has the highest per-capita dependence on groundwater in the country. Half our population takes water for drinking and cooking from wells. It is the wild, wild West because well water is exempt from state and federal safe drinking water laws.”

He expressed dismay that Gov. Paul LePage vetoed a bill proposed last year by Rep. Drew Gattine, D-Westbrook, that would have promoted well water testing. Gattine’s bill was prompted by a Dartmouth University study that found that 150,000 Mainers could be drinking from wells with high arsenic concentrations. LePage called the bill “unnecessary” and the Legislature did not override his veto.

Arsenic has a serious impact on brain development in fetuses and children and has been tied to cancers.

“Lead, like arsenic, is a serious neurotoxin,” Believeau said. “It robs our youth of intelligence and the ability to succeed.

“It is not enough to say that it is up the individual to protect themselves,” he said. “We need public policy. It is a matter of environmental justice.”

In Maine, incidences of corrosive water appear most likely in southern and coastal counties, according to maps distributed by USGS. As with the arsenic so often found in Maine well water, which comes out of the granite bedrock, the corrosiveness of Maine’s groundwater is unavoidable – it’s linked to the state’s geology and geography. As pointed out by Kenneth Belitz, chief of groundwater assessment for the USGS National Water-Quality Assessment Project, groundwater often becomes more corrosive closer to the ocean because of salinity.

“The corrosivity of untreated groundwater is only one of several factors that may affect the quality of household drinking water at the tap,” the USGS stated in a “Frequently Asked Questions” section accompanying the national study. “Nevertheless, it is an essential factor that should be carefully considered in testing, treating and maintaining the quality and safety of drinking water obtained from a private water system supplied by groundwater.”

The Maine Drinking Water Program, part of the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, oversees only wells that are part of a public water system. It does not regulate homeowners’ wells, but CDC spokesman John Martins wrote in an email that the Environmental Health Program “is active in providing information to consumers who have concerns about their wells and encouraging the testing of wells.” However, the primary focus of that outreach has been to increase the number of wells tested for arsenic.

Corrosive groundwater can interact with the metals used in household plumbing, resulting in the leaching of lead, copper or other chemicals into the drinking water or preventing pipes from accumulating a mineralized coating that can protect against leaching. Leaded pipes and fittings were commonly used in homes built before 1930, but high amounts of lead were still used into the 1980s in the solder connecting pipes and fittings. Even supposedly “lead-free” brass or galvanized steel components were allowed to contain some lead until 2014.

The National Ground Water Association, based in Ohio, urges homeowners in areas with corrosive water to investigate and determine whether lead is present in their drinking water.

“The best way to know if you have a lead problem is to test at the tap,” said Cliff Treyens, the association’s communications director. “If the test is positive for lead, the next step would be to determine the source of the lead. By taking samples at different locations from the well to the tap, the source can be isolated.”

Treyens said water can be treated to make it less corrosive, so that it doesn’t leach lead from pipes or fittings. Other treatment systems remove lead from water at the tap.

“Also, another way to eliminate lead-tainted water is to run water that has been sitting in the system for a long period, such as overnight, until it turns cold before drinking it,” he said.

The USGS study analyzed untreated groundwater samples from about 27,000 locations. Unlike public water systems, which must undergo a regular regime of testing, private wells are not regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The USGS study was released less than a year after the drinking water crisis in Flint, Michigan, made international headlines. A 2014 decision by state and local officials to switch Flint’s drinking water supply from Lake Huron to the more corrosive Flint River produced dangerous lead levels in the city’s water supply, causing lead poisoning among the city’s children and forcing residents to switch to bottled water. But Belitz and other USGS officials stressed that their study was not applicable to the situation in Flint because it was river water, not groundwater, that had been inadequately treated to address corrosivity issues.

“The USGS study is only reporting on the potential corrosivity of untreated groundwater, with the implications of having potentially corrosive water directed primarily at homeowners who rely on private wells for their drinking water supply,” the USGS wrote. “Unlike public water supplies like Flint, the quality and safety of drinking water from private wells are not regulated by the federal government or, in most cases, by state laws. Rather, individual homeowners are responsible for testing, treating and maintaining their private water systems.”

But Beliveau, of the Environmental Health Strategy Center, said it is time for that exemption to be reviewed. Although it might be possible for some well users in Maine to be connected to municipal drinking-water systems, the large rural population spread out over a vast geographic region means that’s not going to be possible for everyone. He wants to see well water tied into safety programs nationwide.

“We’ll be back in the Legislature next year,” Beliveau said. He said a bond measure could help low-income Mainers address problems with their wells.

In the meantime, he said, Mainers on wells should take a serious look at their water sources. That’s what he’s going to do. A fix at the faucet could cost as little as $400, Beliveau said.

“I’ve tested my well for arsenic, but based on this new study I am going to go back and test for lead,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.