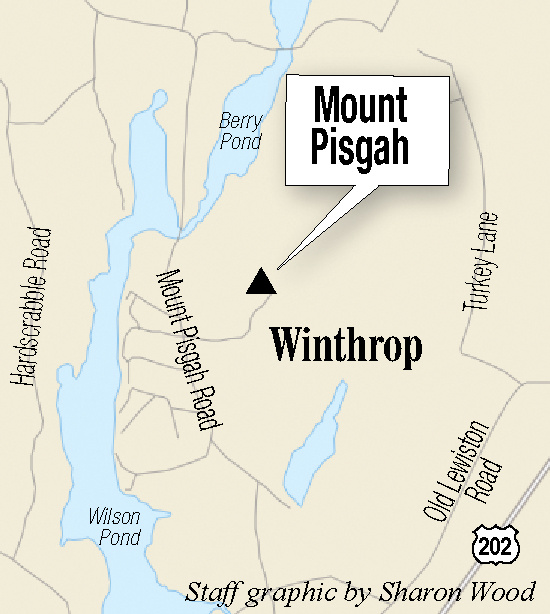

WINTHROP — When locals and travelers come to Mount Pisgah, it’s often to walk up and around the small mountain.

If they’re feeling adventurous, they climb the 60-foot fire tower at the top — a panoramic cherry on a sundae of oak, pine, maple and rock — that on a clear day offers views of Mount Washington to the west and the Camden Hills to the east. The mountain’s name, Pisgah, comes from the Hebrew word for “lookout.”

But there’s a project underway that could soon bring people here not just to gaze at the surrounding vistas, but to peer in on the mountain’s flora, and maybe even find Maine’s most famous fruit.

Highbush blueberries used to flourish on and around Mount Pisgah, according to conservationists with the Kennebec Land Trust, an organization that manages more than 4,660 acres of land in central Maine, including the Winthrop mountain.

The wild fruit grew because settlers who began arriving in the Winthrop area in the 18th century cleared the mountain for farmland, allowing sun to shine on swaths of earth that had been shady forest for thousands of years.

Blueberry bushes still grow on Mount Pisgah, but they have flowered less and less in recent years.

That’s because of local conservation efforts that have allowed second growth oaks and pines to again thrive, but at the same time have blocked sunlight from the understory where blueberry bushes grow.

“Sun is the source of all energy,” said Dave Yarborough, a blueberry specialist at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension. “If the blueberry plants don’t get sun, they don’t get energy, and they can’t make fruit.”

Jim Connors, a Bangor native and a volunteer steward with the Kennebec Land Trust, first heard about the blueberries on Mount Pisgah when he moved to central Maine in the early 1970s.

“Our neighbors always mentioned picking blueberries,” recalled Connors, who now lives in North Monmouth near the Mount Pisgah trailhead and grows blueberries in his dooryard.

So about two years ago, after Kennebec Land Trust opened a new, 1.6-mile trail up Mount Pisgah — a path that is aptly named Blueberry Trail — Connors suggested clearing a small section of the forest halfway up the mountain to allow blueberries to again grow in abundance.

Officials with the Kennebec Land Trust agreed to the plan. They found a volunteer, Mike Simoneau of Monmouth, to clear 4 acres of trees on Mount Pisgah. Simoneau and other volunteers completed much of that work last winter and spring, and the land trust now expects the restored field to begin producing fruit in the fall of 2017, said Stewardship Director Jean-Luc Theriault.

“It’ll be for the community eventually,” Theriault said, “so families can come up and pick berries.”

Next steps for the project include pruning the blueberry bushes on Mount Pisgah to promote growth and continuing to clear trees and other plants as they sprout. The oak trees that Simoneau felled will be removed for fire wood, while the pines will be left to decompose.

Highbush blueberry can grow up to 6 feet, but Mount Pisgah is also host to a few lowbush blueberry plants, said Theriault.

Lowbush plants grow up to 2 feet and account for a far larger chunk of Maine’s iconic blueberry industry.

Yarborough, the University of Maine blueberry specialist, estimated there are 44,000 acres of commercial, lowbush blueberry crop in Maine concentrated largely along the coast and just 200 acres of highbush crop.

It’s not clear to those who have worked on the Mount Pisgah project whether the highbush blueberries were naturally occurring or planted by settlers many years ago.

“There’s no evidence of people planting them, so as far as we know, they’re all natural,” said Toby Smith, a Kennebec Land Trust intern who researched the history of blueberry picking on Mount Pisgah as part of a research project this summer.

Smith, 20, is a Manchester native who now attends the University of Vermont.

The culmination of his project is a brochure that explains that history. The brochure will eventually be available at the trailhead and in the Kennebec Land Trust office.

Smith and the land trust’s other intern, Josh Caldwell, a West Gardiner native who attends Bates College, both spent a few days clearing the 4-acre blueberry field on Mount Pisgah this summer.

In the brochure, Smith included the perspectives of several older area residents who either picked berries themselves or farmed on the property around the mountain. One person Smith interviewed was Eva Smith, of Readfield, his grandmother, whose family went picking there twice a week in the 1960s.

“I actually learned that by accident,” Smith recounted. “I brought up that I was doing this project, and she said she picked blueberries there when she was younger.”

But as Smith noted in a draft version of his brochure, “their picking years were cut short by the continuous growth of forest.”

His grandmother did transplant several plants to her own property, where they now produce fruit every year, he noted, and “Her homemade blueberry muffins are a testament to just how delicious a wild blueberry can be.”

Even with the dense tree cover that has sprung up on Mount Pisgah in the last few decades, a few berries still have grown there.

One recent visitor to the mountain was happy about that, as well as the possibility that more berries could grow in coming summers. Tim Williams, of Boston, was on vacation in Litchfield and hiking on Mount Pisgah on a recent morning.

During a rest in the new 4-acre clearing, he remarked, “I got all excited when I saw the blueberries and said, ‘A blueberry on the Blueberry Trail!'”

Told of the new blueberry field, Williams added, “This is great, a real public service.”

Charles Eichacker — 621-5642

Twitter: @ceichacker

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.