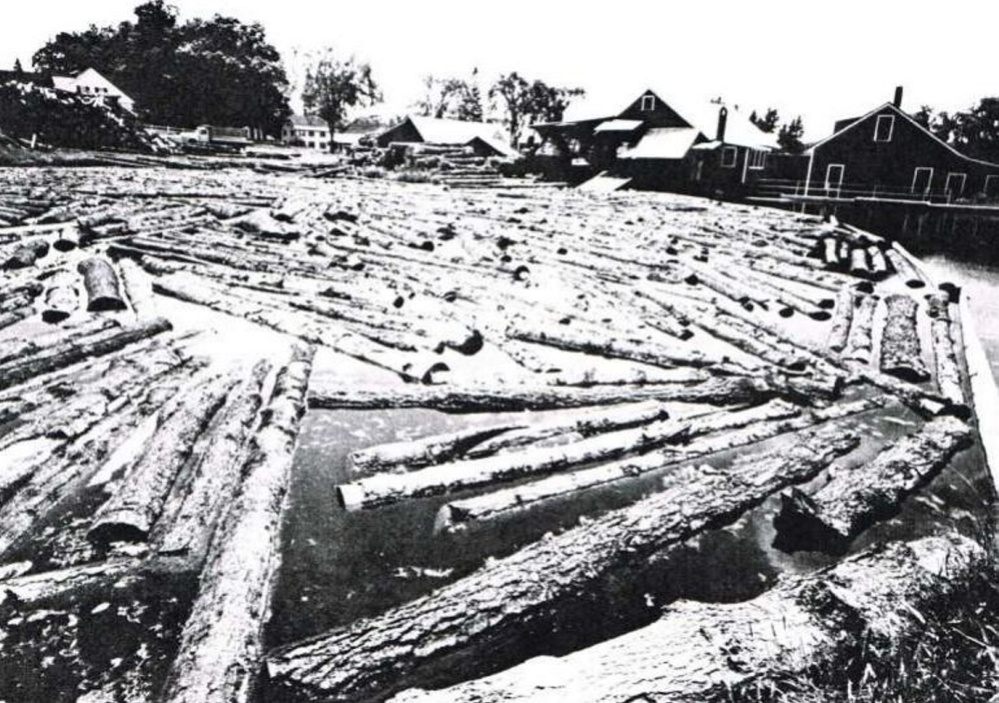

VASSALBORO — Around 1800, a sawmill was built along Outlet Stream. In 1912, the sawmill, along with its water power rights and the neighboring grist mill, was sold to the Masse family, who owned the dam.

Donald Robbins, a descendant of the Masse family, is now “presiding over the funeral” of the historic site, which was partially torn down last week.

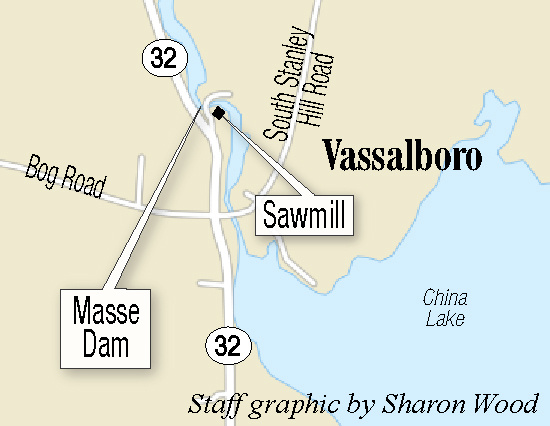

The Alewife Restoration Initiative, an unofficial collaboration of seven organizations, tore down the sawmill for safety reasons and plans to remove the Masse Dam as part of a project to restore the alewives to China Lake, giving them access through Outlet Stream. The alewife group plans to remove four dams along Outlet Stream and install two fish passageways at other dams.

But not all residents are at peace with the sawmill removal or satisfied with the way the group is conducting the dam removals. Some even protested the removal of the Masse Dam earlier.

The history of the sawmill begins in 1797. Nathan Breed received 1.5 acres of a mill yard to build a sawmill, as well as half of the water power rights from the Outlet Stream. In the early 1800s Jacob and then Henry Butterfield gained ownership of the sawmill.

“It’s been a mainstay of the village since 1800,” Robbins said.

In 1872, the Vassalboro Woolen Company bought the entire site: the grist mill, sawmill and all of the water power rights.

The mills were leased and changed ownership over the years until all pieces were sold to the Masses in 1912. Louis Masse improved the structures, building a concrete dam upstream from the timber and stone dam and turning the grist mill into a machinist and woodworking shop.

Robbins’ second cousin, Ken Masse, owned the property through the 1950s and made several upgrades.

His son Matt Masse inherited the site and leased it to a former foreman while he worked at Hammond Lumber. The foreman died in 2000. That was the last year the sawmill was operational.

In 2006 Robbins and his business partner bought the water company portions of the property to run the East Vassalboro Water Company, which is also a Masse family business. In 2010 they used money from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to buy the rest of the site as “wellhead protection.”

In the years following 2000, without anyone to run the sawmill, snow fell onto the live deck in the wintertime. Ice cascaded onto the sawmill’s floor and froze in doorways, breaking up concrete. The roof leaks, rotting out major beams and underlying rafters. Some beams eventually cracked. The granite block retaining wall next to the gristmill was in the process of collapsing. A storage room’s floor collapsed into Outlet Stream in 2015.

SAFETY AND HISTORY

Robbins said he has mixed feelings about the sawmill coming down. It’s been in his family since 1912, but there was no possibility of saving it.

The older equipment and labor-intensive work outweighed the revenues the sawmill made. The mill couldn’t cut enough wood to earn its keep, so the family stopped using it.

Robbins is a geologist and has environmental interests in addition to the water company. He and his partner bought the property as a requirement to protect their water source and pipes.

But being a water company, the Public Utilities Commission wouldn’t allow them to borrow money to shore up the building so it wouldn’t collapse. For that alone, estimates from multiple engineers ranged from $250,000 to $300,000, he said.

Demolishing the building wasn’t in their price range either. In 2010 the company used a bartering process to pay a contractor to take down part of the sawmill.

The building posed multiple problems. It was on the brink of collapse, which could potentially break water pipes that are in the water. People, especially children, would sometimes trespass on the property to check out the interesting, seemingly abandoned building, which was a liability issue for the owners.

The sawmill “just sat there and it kept getting worse and worse,” Robbins said. “We’ve been living with ulcers and nightmares and sleepless nights.”

In 2013, the Alewife Restoration Initiative came along with a proposal to tear down the sawmill and remove the Masse dam.

“We thought it was such a godsend,” Robbins said. He sold the building to the group, which did the fundraising for the project.

The sawmill was torn down on Wednesday. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, so the Alewife Restoration Initiative was required to go through an exhaustive process of documenting the site, according to Landis Hudson, executive director of Maine Rivers, which is part of the alewife group.

Hudson said the group worked to recover whatever historical pieces they could before the building was torn down. Members of the alewife group and officials from the Maine Forest and Logging Museum in Bradley went through the building to retrieve historical pieces to be preserved at the museum, she said.

The grist mill, which also has historical pieces and equipment, will remain standing. Still, it’s strange for Robbins to see the other mill come down.

“It’s as though I’m conducting the last rites,” he said.

Some residents thought the announcement of the demolition was short notice. While Hudson said they’d been in contact with the Vassalboro Historical Society for months about the plans to eventually tear down the sawmill, the organization’s president, Janice Clowes, said at an informational meeting that she thought they weren’t given enough say in what happened.

“I think we didn’t feel like we had the opportunity to talk about how we could save it,” Clowes said.

But with the removal of the sawmill comes more security for the 200 or so people who rely on the East Vassalboro Water Company for clean water every day. The alewife group is also relocating water pipes along Stanley Hill Road for the company now that the sawmill, which could have collapsed, is out of the way.

The water level at Outlet Stream has been lowered in anticipation of the removal of the Masse Dam, and the water pipes need to be relocated so they don’t freeze over in the lower water. If the dam were ever to breech, the pipes could break, which would be “catastrophic,” Robbins said.

The change will affect about five homes, which will get individual service sent to their homes. The work is expected to run Sept. 12 through Sept. 30.

WATER ISSUES

The permit-by-rule the Alewife Restoration Initiative submitted to the Department of Environmental Protection was rejected in August because of deficiencies. The licensing project manager at the department also said that the group should be filing for an Individual Natural Resources Protection Act permit instead, as the proposed project could alter wildlife habitats below the dam and possibly impact the environment.

Items missing from the permit-by-rule include the processing fee, appropriate location map, photographs and a scaled plan.

For now, the water level has been lowered, and some residents say that is already affecting them.

Charlie Hartman lives next to the sawmill on Route 32 and said she is upset that her backyard, which once held a pond, now just looks like mud.

“Everything that we’ve been concerned about has already come to pass,” she said after an Alewife Restoration Initiative meeting.

Hartman said people in Vassalboro are upset about the methods the alewife group have been using to achieve their goals.

“Vassalboro has been trying to get the ARI to work with them for months to get a solution,” she said. “I am absolutely certain that that solution is possible.”

Hudson has said that they are looking to get people’s input, and that is why they are holding informational meetings in the town.

The Alewife Restoration Initiative is working on a years-long project that could potentially revive China Lake, restore its water quality and provide revenue for the town.

The lake’s decline didn’t happen overnight. For decades septic systems, fertilizer and road runoff polluted the lake, adding phosphorous which then spawned large algae blooms. It was not only damaging to the aesthetics of the lake, but also the quality and the ecological life. Water quality has an effect on property values, according to a 1996 study by the University of Maine and the Department of Environmental Protection.

The 1980s proved to be a “tipping point” for the lake, according to China Lake Association President Scott Pierz. Annual algae blooms started in this time period and the lake’s water quality rating started decreasing.

To revive the lake will take time. Ecologically, China Lake is “dead,” according to Nate Gray, who works for the state Department of Marine Resources, which has been working to restore alewives across the state.

An alewife is a species of herring that usual grows to about 10 inches in length. It’s also a great form of lobster bait, providing a boon to the industry and creating another, alewife harvesting.

But perhaps the most attractive feature of the alewife for China Lake is that it’s a migratory fish. The only other fish native to the lake that migrates back to the Atlantic Ocean is the eel, which has seen a drastic population drop due to dams.

Alewives spawn in ponds, lakes or rivers and the adults return to fresh water before coming back to spawn in May or June.

When an alewife leaves a lake, pond or river, it takes with it some of the phosphorous from that water. Studies conducted by the state have shown that water quality improves in lakes when alewives are reintroduced.

“It won’t instantaneously reverse the water quality issues of China Lake,” Gray said at an Alewife Restoration Initiative meeting. “But they will help the water quality over the long term.”

However, a study commissioned by the Kennebec Water District and done by Kleinschmidt Engineering found that “there is little evidence that restoring alewife is a panacea for accelerating the recovery of eutrophic lakes.” The study also found no evidence that the fish would have an adverse impact on water quality and suggested that more alewives were good for towns both for economics and for more studies of the effects.

The alewife group hopes that once the alewives can swim both ways between China Lake and the ocean, the town can benefit from alewife harvests. Webber Pond made about $20,000 last year, according to Webber Pond Association President Frank Richards, who spoke at the Alewife Restoration Initiative meeting.

The lake is about three times the size of the pond, so it could potentially get about $60,000 per year from alewife harvesters.

Madeline St. Amour – 861-9239

mstamour@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @madelinestamour

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.