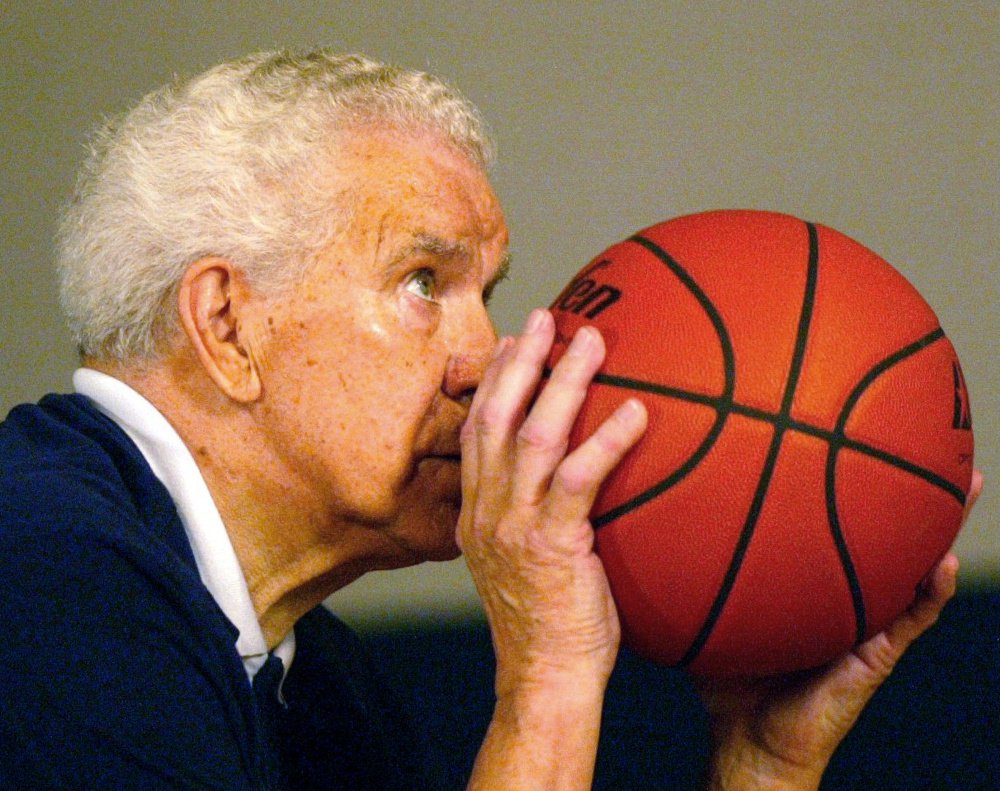

It took 12 hours and 2,750 shots for Dr. Tom Amberry, a 71-year-old retired California podiatrist, to set the world record for free throws consecutively shot and made.

Over and over, 10 bored witnesses watched his six-second routine – parallel feet, three bounces of the ball, bent knees, tight elbows – inside the Rossmoor Athletic Club in Seal Beach, California, on Nov. 15, 1993.

Amberry stopped at the 12-hour mark, but only because the gym janitors made him.

“I could have made a bunch more,” Amberry told the Orange County Register in 1995. “I was ‘in the zone,’ as the kids say.”

In the quarter century that followed, Amberry wowed David Letterman and Tom Brokaw on TV, wrote a free throw guide book, “Free Throw: 7 Steps to Success at the Free Throw Line,” and traveled the globe teaching players young and old, amateur and all-star, how to master the least sexy way to win a basketball game.

Nothing irked him more than sloppy form, poor focus and irreverence at the line.

“A free throw is a gift,” he would say. “You should take advantage of it.”

Coaches, filmmakers and journalists sought Amberry’s free throw analysis well into his nineties, and on more than one occasion he offered his critiques from the comfort of his couch, particularly during the NCAA tournament.

On March 18, amid the height of March Madness, Amberry died in California.

He was 94.

Like many country kids, Amberry spent his boyhood shooting at a hoop on the side of his barn in Grand Forks, North Dakota, snow and ice notwithstanding. When his mother forced him indoors, he shot at a mark above the kitchen door instead, the Los Angeles Times reported in 1995.

At a lanky 6 feet, 7 inches tall, he played basketball and baseball in high school and graduated in 1940.

But he was called off to World War II soon after and spent four years in the Navy, fighting in the D-Day invasion at Normandy and against the Japanese in the Pacific theater. He played on a Navy basketball team.

The war ended and he returned to California, where he joined the team at City College in Long Beach, California. The opportunity for a sports career waited with the Minneapolis Lakers, which offered him a two-year, no-cut contract. But Amberry turned it down and went to podiatry school instead.

For the next 40 years, he didn’t touch a basketball. He and his wife, Elon, raised four sons and in 1991, he retired.

That’s when Amberry got very bored.

He would wake up, water the yard, stare into space.

“At the end of the day, I felt I didn’t accomplish anything,” he told the LA Times. “I mean, how many times can you vacuum the carpet and get satisfaction from it?”

At the suggestion of a friend, he grabbed a basketball. Amberry had heard there were free throw contests in the Senior Olympics and he was determined to qualify.

A competitive taunt spurred his motivation.

“I had no concept of a method – just step up to the line and shoot,” Amberry told Sports Illustrated. “A couple of months after I started, I met a guy at a Senior Olympics free throw competition in Palm Springs who had been coaching high school basketball for 28 years, and he said, ‘You won’t beat me because I’ve shot 30,000 free throws in the past two months.’ ”

So Amberry practiced, and studied, and then practiced some more. When he exhausted his left arm, Amberry switched to his right. Slowly, methodically, the retiree improved. He would spend the rest of his life preaching the importance of routine.

Every morning – except Sunday – he began his day at the Rossmoor Athletic Club, the scene of his eventual record-setting feat. He wouldn’t leave until he’d launched 500 shots.

“If you’re going to do something, why not be the best?” he once said in an interview.

According to Amberry’s own meticulous records, he consecutively netted all 500 of those shots on 473 separate occasions.

A 1994 Sports Illustrated profile explained Amberry’s process:

As he traveled around competing, he incorporated into his routine pointers from various free throw experts. Mike Scudder, a former player at St. Joseph’s College in Rensselaer, Ind., who gives free throw demonstrations at the school’s basketball camps, taught Amberry to keep his feet parallel, square his shoulders to the basket and bounce the ball three times – “always with the inflation hole up,” says Amberry, “because it’s the only thing common to all basketballs, and that way you can always grip the ball on the same seam.”

From John Scott, who produces instructional videos, Amberry learned the importance of keeping his shooting elbow in. (“There are only four ways to miss – long, short, left and right,” says Amberry. “This eliminates left or right.”) Buzz Braman, who works with the Orlando Magic, stressed keeping one’s eye on the basket. And from Floyd Strain, a sports psychologist in Payette, Idaho, Amberry picked up the trick of visualizing his arm as 15 feet long and dropping the ball into the basket, which helps sustain his follow-through.

After he set the world record, Amberry made the rounds of the 1990s TV show circuit: Letterman, NBC Nightly News with Tom Brokaw, Jay Leno, ESPN, Ripley’s Believe it or Not.

One sports writer once asked if he was a savant. True to his own gospel, Amberry fired back: “If I am, why do I have to practice so much?”

In retirement, Amberry taught free throw clinics in all 50 U.S. states, more than 100 countries and at least five continents.

One of the first was at Long Beach State, where he marched into the office of then-assistant basketball coach John Welch and declared he was the “world’s greatest free throw shooter” and wanted to help the program.

Welch said he had to improve his shot first, then he could critique the players.

“The first day I hit 68 in a row. The second, I hit 99 out of 100,” Welch said in the SI interview. “That was proof enough for me.”

Amberry co-wrote his book in 1996, which the Los Angeles Lakers reportedly gave to their own notoriously troubled free throw shooter, Shaquille O’Neal. He consulted with hundreds of college basketball programs in the decades that followed and even served as a special assistant coach for the Chicago Bulls for two years in the early 2000s.

He often shared with young players his trademark line: “You’re more limited by your beliefs that your abilities.”

In a section on his website called the Coach’s Corner, his motto is immortalized:

“A free throw is a gift,” he wrote.

Amberry was preceded in death by his wife, Elon, and one son, Tim. He is survived by sons, Bill, Tom and Robert; 12 grandchildren and 11 great grandchildren.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.