When you look northeasterly in the evening, now that it’s getting dark early again, Cassiopeia is fairly easy to pick out. A lopsided W of stars that in myth depict Queen Cassiopeia, who was imprisoned in a chair in the sky for thinking too much of her own beauty. Her daughter, Andromeda, is the constellation of mostly fainter stars toward the east. Underneath Cassiopeia is Perseus, who rescued Andromeda from the sea monster Cetus (who is swimming invisibly down under the horizon in our autumn). Perseus also killed the Gorgon Medusa and, in his star-outline, dangles her perilous, bloody head from his hand.

The star that denotes the head is Algol, or “the ghoul,” after the Arabic, al-Ra’s al-Ghul, the Head of the Ghoul. It has been regarded as deeply ill-omened since time immemorial. Why, is lost in the depths of time. Perhaps. Ancient Hebrews called it Rosh ha Satan, Satan’s Head. Worlds away, Chinese astronomers called it Piled-up Corpses. The Romans used versions of Caput Gorgonis, the Gorgon’s Head.

We call the story of Perseus using Medusa’s head as a weapon to rescue Andromeda a “myth,” a word scientists of the past century have made synonymous with “falsehood.” And in this spirit, some astronomers turn the ancient sense of Algol’s evil on its head, and jocularly observe that Algol is actually a “friendly” star because it provides unique information. And information is good.

The prince of darkness, it has also been observed, is a gentleman.

This response from me, who’s a doctor but not a scientist, could result in mean laughter and my own demonization, I know. I’m of two minds about this.

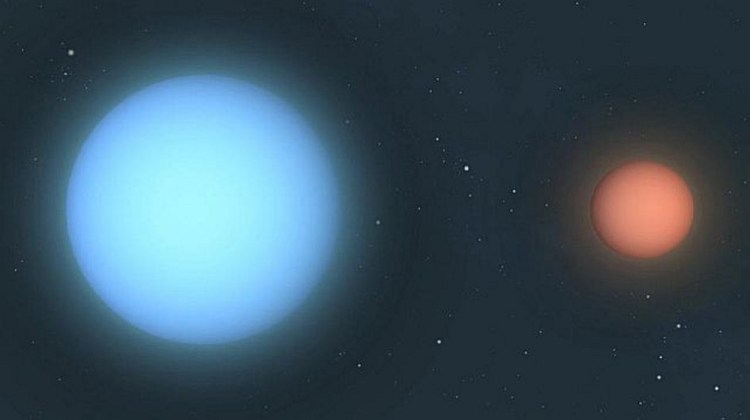

One mind profoundly respects the scientific facts. Algol is one of the fascinating stars. It was the first “variable” star identified as an “eclipsing binary,” meaning it varies between brighter and dimmer because it’s actually two stars orbiting each other, with the darker periodically eclipsing the brighter. A third star circling the other two sometimes jostles the eclipse.

What’s weird, from a scientific viewpoint, is how often the eclipse happens: every 2.8 days. The two stars whip around each other less than 6 million miles apart (it’s about 93 million miles from the Earth to the sun). The larger star, a Class K giant, is paradoxically the dimmer of the two. When it cuts between us and the smaller but brighter Class B star, it shuts out light, and to our eyes, the system dims. Weirder still, material is flowing off the surface of the older K star into the younger B star.

These are fascinating astrofacts. But in some inevitable way, the data about this extremity in the sky sink into my other mind and get a life of their own. The B star is cannibalizing its elder.

Algol is best seen from Maine in fall, and one October night of broken clouds long ago, I spread the three legs of my small telescope in a field and pointed it toward Perseus. In the blackness inside the lens, Algol quaked and glinted. It’s white but has a peculiar shadowiness. I watched it shift, in the lens, from fiery to a sort of lurid dimness. Kind of strange, there in the field.

Cars were rushing along the road the other side of the trees. A barred owl ran its haunting song onto the chilly air. Some unidentified rustling in the brush. That starlight, uncannily variable in both clouds and scientific fact. Pretty soon the back of my neck was prickling.

This cold night will turn us all to fools and madmen, I thought. Then a low-pitched, hollow whistling boiled out of the trees, more horrible than anything I’ve heard before or since.

I froze. Suddenly I was so scared my fingers trembled, and for a moment my mind was split. A calm part of me was watching another, petrified part which would have run for the road if it could have gotten control of my legs.

I looked up from the dim image in the telescope lens, which seemed to be generating the fear. The whistle subsided. What animal is that loud and terrible? What’s dead in that thicket?

Reassembling my wits, I pointed the telescope away from Algol and homed in on a breath of fresh light from galaxy M31, halfway between Andromeda and Cassiopeia. Then I packed up and scrambled home.

All this must seem pretty foolish. A star is not a Gorgon. But fishing in the dark for sanity, as I’ve done hundreds of times, my thoughts by some combination of fact and fiction ended up in fear and trembling.

Apparently the ancient astronomers had some such experience too. And took it seriously. Myths, I want to say, originate in reality of some kind.

Dana Wilde lives in Troy. You can contact him at naturalist1@dwildepress.net. His recent book is “Summer to Fall: Notes and Numina from the Maine Woods” available from North Country Press. Backyard Naturalist appears the second and fourth Thursdays each month.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.