In September, after the Democrats and Republicans hold their national conventions, the presidential election will begin in earnest, and we will be bombarded with reminders about everything that divides us as a nation.

Before the campaign divides us, let us take time this August to enjoy — as Americans — the spectacular demonstrations of American achievement now on display: the performance of our athletes at the Olympics and the successful landing of the Curiosity rover on the planet Mars.

Not many Americans avidly follow track and field sports, or volleyball, or swimming and diving, or gymnastics, or even soccer, except when the Olympics come around.

We could see the same pure athleticism and displays of physical excellence if we watched the annual world championships in these and other sports, but we don’t tune in. Except for the Olympics.

What draws us to the Olympics is the spectacle of our nation’s best athletes, representing the United States, in competition with other nations’ best athletes, who are doing their best to bring honor and victory and glory to their own countries. In just about every interview, our Olympians’ pride in representing the U.S. is evident, and their patriotism is infectious.

It may seem odd that those of us at home or in the stands, who will never ourselves be world-class athletes, should see our Olympians as representing us, or should feel vicarious pleasure in our athletes’ victories. Their achievements, like their failures, are truly their own.

Yet we can and do embrace the Olympic athletes as representative because they exemplify a form of achievement that Americans widely share — athletic accomplishment. We feel their victories as our own because they embody what we wish we could be and do, though we know we can’t.

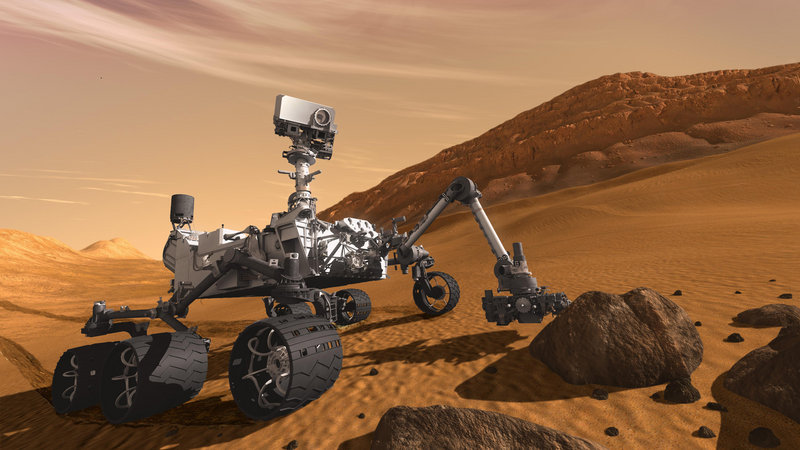

If you can turn away from the Olympics this weekend and want to enjoy another spectacular American achievement, take a look at some of the latest pictures beamed back from the Mars Curiosity rover.

Curiosity is a six-wheeled vehicle, roughly the size of a small car, bristling with cameras and sophisticated sensing equipment. American scientists and engineers built it, guided it successfully through an eight-month, 300-million-mile journey and managed to land it safely, exactly where they wanted to. On another planet.

To get a sense of how awesome an achievement this is, go outside on the next clear evening and look at the sky near the southwestern horizon. Forming a little triangle, you should see three bright objects — the whitish one will be the star, Spica, the yellowish one is Saturn, and the ruddy one is Mars.

Mars is so far from us that you can’t see its planetary disk without using a telescope, and this week, Americans landed a spacecraft there. (As it happens, we also have a space probe orbiting Saturn, taking pictures and collecting data, but that’s old news: it arrived at Saturn back in 2004).

To get a one-ton piece of equipment to land softly on a planet with a thin atmosphere is about as difficult as you might imagine.

First, the probe was slowed by friction between the thin Martian air and a heat shield; then, when the probe was moving slowly enough, the shield was jettisoned and a giant parachute opened.

After the chute did its job, it was discarded, and the lander fired rockets to slow its fall. For the final approach, the rover was lowered by a cable from the hovering probe down to the planet’s surface. After Curiosity had landed, this rocket-powered “sky crane” was crash-landed some distance away.

It is remarkable enough that each part of that process worked perfectly, but we have direct, photographic evidence. Another American spacecraft, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, photographed the parachute stage of the descent, and it also has sent back pictures of Curiosity’s landing site, on which the rover, its heat shield, parachute and the “sky crane” are all visible.

Not only can Americans land a car-sized rover on Mars, American engineers can take a picture of it from another spaceship, while it is happening!

The real scientific work of the mission has yet to begin, and whatever scientific discoveries the mission yields will become the common heritage of mankind, just as new world records set at the Olympics will stand as achievements for all to emulate.

For now, though, we — as Americans — should come together to take pride in the ambition and skill of our athletes in London and in the technical prowess of our space scientists.

Joseph R. Reisert is associate professor of American constitutional law and chairman of the department of government at Colby College in Waterville.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.