WATERVILLE — In the X-ray room at Inland Hospital, three women crowded the X-ray table, on which a portrait of a young girl was lying.

The girl’s delicate white dress was translucent in places and draped softly over her shoulders. In her hands she held a small bouquet of flowers.

The women had a suspicion that the dress did not appear in the painting the way the artist originally had intended. They believed it had been painted over years after the portrait of Kitty James was made, to reflect changing fashions years later and perhaps cover up damage.

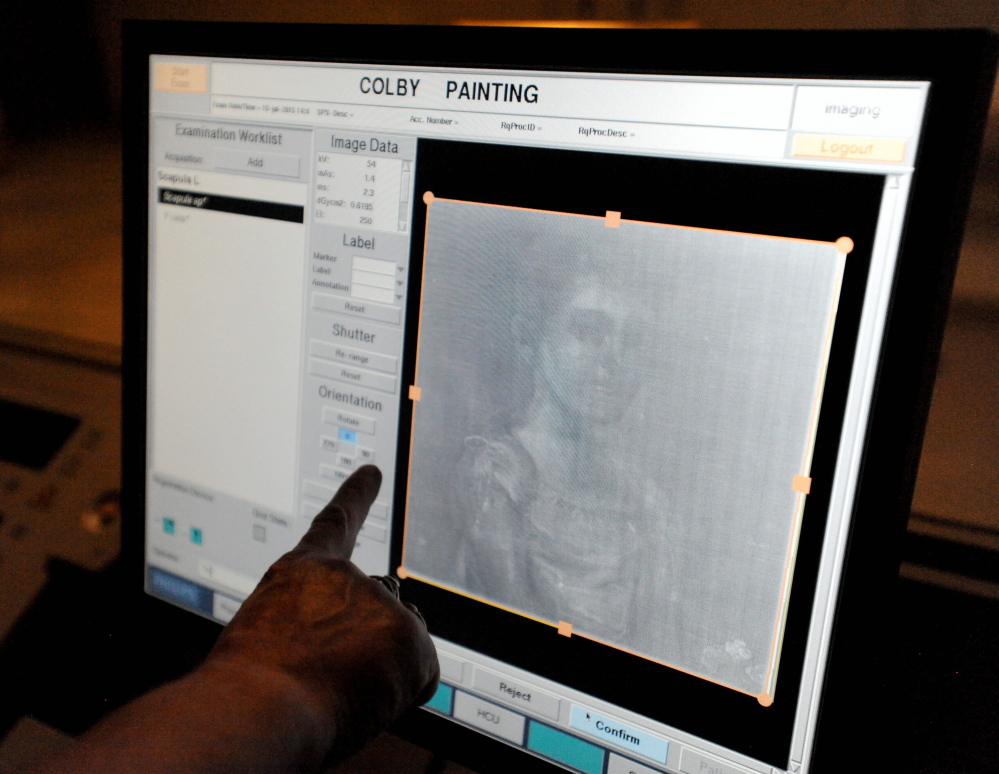

As the X-ray machine slid over the painting, a black-and-white image of the dress appeared on a computer screen, revealing a tassel hanging from the sleeve and confirming the women’s suspicions.

A ruffle graced the dress collar and a pearl necklace lay hidden under a layer of cruder flesh-colored paint around the girl’s neck.

“It’s such a prettier dress than the one she’s wearing,” said Lauren Lessing, a curator at the Colby College Museum of Art and the director of academic and public programs, as she pointed to the tassel on the computer screen. Though hidden under a layer of oil paint, the tassel, created in lead paint, showed up in the X-ray, revealing the painting as originally created by the artist, Ezra Ames.

“Oh, awesome. That is really cool,” agreed Nina Roth-Wells, a conservator who is working to restore the painting. The museum plans to include the work in an upcoming showcase of American folk art in the summer of 2016, and it hopes to be able to show it the way Ames first painted it.

The use of X-rays to reveal such details is rare and was a first for the Colby museum, as well as for the hospital.

“It was Nina’s suggestion,” Lessing said. “She said, ‘Well, why can’t we just use the hospital X-ray machine?’ and she did research to see if other people have done this, what kind of settings you would need to X-ray the painting. She figured that out. Then when we called the hospital, they were surprisingly enthusiastic about the whole project.”

Tina Hintz, director of imaging services at Inland Hospital, said that while she had never X-rayed a painting before this week, she has X-rayed other unusual items, including a set of duck decoys while she worked at Franklin Memorial Hospital in Farmington. The decoys’ owner wanted to see if they had been tampered with, and the X-ray process revealed that some screws were missing, Hintz said.

The process for taking the X-ray of the ducks, or of the painting, doesn’t vary from the way the hospital would take an X-ray of the human body, she said. A machine works to send electromagnetic radiation — X-rays — through the objects. The X-rays pick up on different radiological densities in the object to generate an image of what it looks like. Heavy metals such as mercury or lead contained in older paints will show up as white patches in an X-ray.

“It’s not common,” said Andrea Chevalier, senior paintings curator at the Intermuseum Conservation Association in Cleveland on the use of X-rays in art conservation. She said the association, which works on about 400 conservation projects per year, gets a request for an X-ray of a work only about once every three to four years. The technique can be helpful in helping curators learn about the construction or condition of a painting, but it also has become increasingly uncommon with the decline of film X-rays because fewer museums are outfitted with digital X-ray equipment.

The question of whether to make changes to a work can be a difficult one for curators, especially since the removal of paint cannot not be reversed; and if the changes were made by the original artist, they are often kept.

However, if the changes were made by a different and less skilled artist, as is the case with the portrait of Kitty James, it can be desirable to remove them, Lessing said.

“What we’re basically trying to do is bring it back to the way it originally looked in 1822,” she said. “As Nina has begun to remove the paint, we’re seeing a much better painting emerge from under the surface of what at first appeared rather crude.”

A largely self-taught painter, Ezra Ames was a New York state-based folk artist who specialized in middle-class portraits of families such as the Jameses, who owned much of the property around the Erie Canal. Ames was not in the top echelon of elite painters of the 19th century, but his work is an example of a large movement among middle-class families to have their likenesses captured in portraiture, Lessing said.

He was also a highly skilled painter and was particularly known for his ability to create a translucent effect in the way he painted flesh and captured fabric.

William James, an Albany businessman, hired Ames to paint portraits of his entire family, including his 2-year-old daughter, Kitty. Originally completed in 1822, the portrait was partially painted over by an unknown other painter, likely to reflect the fashion of later years.

“The painting was basically painted over to make it look a little more up-to-date,” Lessing said.

To the average viewer, the changes are seamless; but as Lessing and Roth-Wells pointed out, there are subtle differences that indicate a different style and quality of painting. The translucent color of Kitty’s dress is much denser around the sleeves and waistline than it is at the end of the skirt.

Her skin tone is rosy and pink in some places, but in areas where it appears painted over it is more opaque and orange.

One of the first things that Roth-Wells removed from the painting were brown lines, meant to indicate the flow of the fabric, but that were flowing in the wrong direction compared with the rest of the dress.

As a conservator, her goal is to return the painting to the way the artist would have envisioned originally. That means removing dirt and grime that has accumulated as well as correcting any alterations to the painting.

“If we were a history museum or a historical society, our philosophy might be different,” Lessing said. “It might make more sense to keep those changes in place as part of the story of the portrait and how it was used by the family. But as an art museum, we’re much more focused on the intent of the artist.”

For the American folk art show alone, Roth-Wells is retouching 15 paintings. The college also will catalogue about 60 works, with about half of them being restored in the process.

Roth-Wells said she recommends that paintings get cleaned at least every 50 years to stay in the best condition. After this week’s X-ray session, the curators went home with a CD of digital images that Roth-Wells will use to bring the tassel on the sleeve, the translucent dress and the pearl necklace back into existence.

They also have plans to come back. “It’s kind of a pilot case for us,” Lessing said. “There are other items in the collection that we’d like to X-ray, so it could become a regular thing for us.”

Rachel Ohm — 612-2368

Twitter: @rachel_ohm

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.