Laurie Bachelder admits that, until one traumatic morning two weeks ago, she “had blinders on” about heroin in Portland because her family had not been touched by the growing drug problem.

Then fate intervened.

During a rare visit to Deering Oaks park with her two young children, Bachelder watched as a man in his 20s stumbled through the popular wading pool before collapsing to the pavement just a few dozen feet from her family and several others gathered at the pool. She quickly ushered the group of children away from the scene as others called 9-1-1 and rushed to help the man, who had a hypodermic needle stuck in his neck and was turning blue from lack of oxygen.

“This was life-changing for me,” Bachelder said. “It hit me like a ton of bricks that this stuff is everywhere. … So I had to do something.”

Rather than recoil from the shocking experience at the park, which city officials say has become a hot spot for drug users, Bachelder has met with recovering addicts at the Portland Recovery Community Center, talked with treatment agencies and now plans to volunteer her business and professional skills to help those trying to piece their lives back together. And she is talking with friends and family members in an effort to convince others to “see past the addiction” and find ways to help the growing number of people who are struggling with opiate addictions in Maine and nationwide.

“After seeing that, I thought, ‘If I can help one person, then maybe that one person can help another person,'” said Bachelder, a Portland resident who runs a financial investment firm in the city.

That is the type of response members of the “recovery community” and those working on substance abuse issues would like to see result from the alarming reports of heroin overdoses. Cities and towns are also launching public education and awareness campaigns in hopes of reducing opiate abuse rates and shattering the stigma that heroin is a big-city issue or simply some other family’s problem.

“We have to get ahead of it,” Lt. Jeffrey Lange, interim police chief in the small western Maine town of Paris, said last week before his department held a “town hall discussion on the heroin epidemic” in the Oxford Hills region. “We can’t stand idly by and watch it happen. It’s a disease and we have to help.”

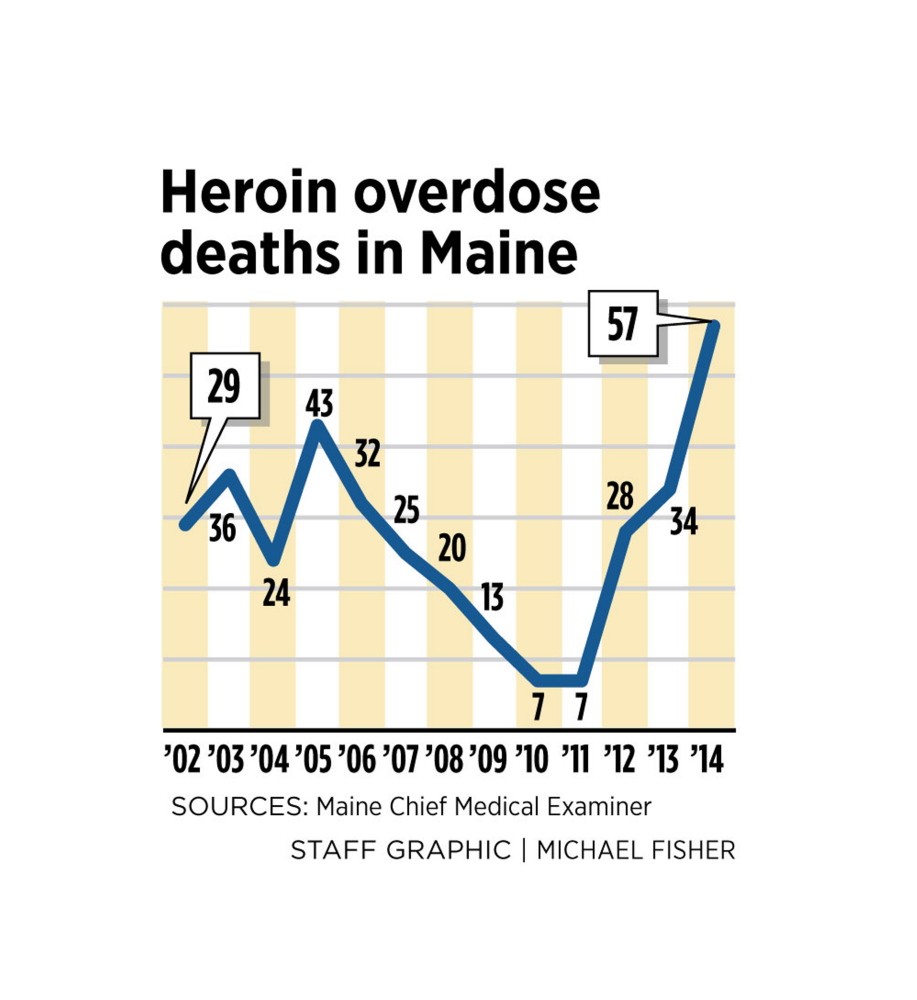

The number of Mainers seeking treatment for heroin addiction increased from 1,115 in 2010 to 3,463 last year while the number of overdose deaths from heroin in the state climbed from seven in 2011 to 57 in 2014. Those statistics reflect the national trends prompted by increased availability of the low-cost street drug at a time when prescription opiate painkillers are becoming harder to find and more expensive to buy. Many users become addicted to painkillers first, then turn to lower-cost heroin.

While Maine’s growing heroin problem has been in the news for several years, the issue received widespread attention again last week, when the city of Portland reported 14 suspected opiate overdoses during a 24-hour period. Police fear that the sudden spike — more than double the number of overdoses of all types on most days in Maine’s largest city — may have been caused by a “bad batch” of heroin that was either of unusually high purity or had been laced with the even-deadlier prescription opiate fentanyl.

City officials responded by promoting the city’s Overdose Prevention Project and discussing plans to seek funds for a program that aims to help police funnel drug abusers through treatment and social service programs rather than through the criminal justice system.

Portland Recovery Community Center is planning the organization’s 2nd annual “Maine Rally 4 Recovery” in Deering Oaks on Sept. 20 featuring live music, speakers, food and activities. The Portland Public Library, meanwhile, is planning a Sept. 24 public forum aimed at raising awareness of the drug and facilitating discussion about the problem.

Darren Ripley with the Maine Alliance for Addiction Recovery, a coalition that works with recovery organizations statewide and helps to facilitate training sessions, said it is saddening that there is still a stigma that paints addicts as hopeless “junkies” or “drunks.” In reality, many people know or work alongside someone who is in recovery or struggling with substance abuse but who keeps quiet because of that stigma.

Ripley believes the spate of news coverage — which has included several hard-hitting obituaries written by the family members of deceased addicts — could be helping more people understand that addiction can affect anyone.

“People are not getting that it could happen here, it could happen to me, or it could happen to my best friend’s son,” said Ripley, who is in recovery from alcohol and drug addictions. “Addiction is not picky.”

Ripley said there are plenty of volunteer opportunities for those interested in getting involved in helping addicts. Ripley trains both recovering addicts and individuals merely interested in helping others to become “recovery coaches” who serve as mentors, teachers and cheerleaders to those struggling with addiction. They can also assist with a telephone recovery support line, provide transportation to individuals without cars or consider hiring someone who acquired a criminal record during their addiction and is working to put their lives on the right track.

One of the places that Bachelder contacted in her efforts to learn more about how she could help was the Portland Recovery Community Center, which offers a gathering place and supportive environment to those struggling with substance abuse.

Steve Cotreau, program manager at the Portland Recovery Community Center, said the center tries to tap into volunteers’ individual strengths, such as Bachelder’s financial background. But he said there are many needs within the community.

“You don’t have to know what you want to do” as a volunteer, Cotreau said. “Sometimes you can come in and we’ll figure it out together.”

Bachelder was so impressed with the people she met at the Portland Recovery Community Center that she hopes to volunteer there helping individuals strengthen their financial planning skills or work on their job-seeking and interview skills.

Bachelder often thinks of the young man, who apparently survived the incident after being taken to the hospital, and hopes that he is receiving help. The sight also affected her young daughter, who wondered aloud for several days whether the man (who she was told had fallen and hurt his head) was doing OK.

But she can’t help think that something bigger prompted her to make an unusual trip to Deering Oaks on the morning of July 28 to witness the “life-altering event” that prompted her to get involved.

“I feel like the universe made that happen,” Bachelder said. “You can’t blindly go through life and not worry about other people.”

For more information on the Portland Recovery Community Center, call 553-2575 or go to www.portlandrecovery.org;http://www.portlandrecovery.org/.

For more information on the Maine Alliance for Addiction Recovery, call 621-4111 or go to www.masap.org/site/maar.asp;http://www.masap.org/site/maar.asp.

Kevin Miller — 791-6312

kmiller@pressherald.com

Twitter: KevinMillerPPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.