It’s been a depressing recovery and expansion for Americans waiting for a meaningful pay raise. It may be time for U.S. workers to lower their expectations for good, if a chorus of economists including Stephen Stanley at Amherst Pierpont Securities and Ted Wieseman at Morgan Stanley are right.

Wages have been climbing at a historically weak 2 percent pace since the end of the 2007-09 recession, and that may be as fast as they will grow, Stanley and Wieseman suggest. Their reasoning is that two main ingredients for long-run pay gains – productivity and inflation – haven’t been increasing as quickly as they had in the past.

A report Tuesday showed that productivity picked up just 0.3 percent in the 12 months through June. What’s more, price increases have remained tempered, with core inflation (which strips out volatile food and energy costs) slowing to an average of 1.5 percent year-on-year growth since 2009. The Fed’s preferred gauge has also missed the central bank’s 2 percent goal for more than three years.

“Over time, workers’ nominal pay should expand by the sum of inflation and productivity growth,” Stanley said in a research note after Tuesday’s release. “Unless productivity miraculously accelerates, anyone waiting for 3.5 percent wage gains is either going to be perpetually disappointed or is going to be knee-deep in an inflationary spiral by the time we get there.”

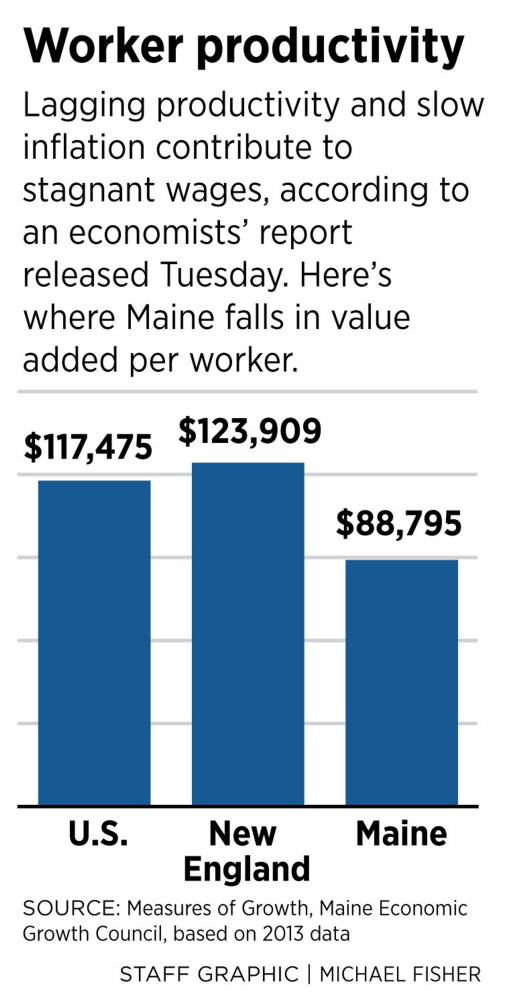

Maine has struggled with worker productivity for years, according to data analyzed by the Maine Economic Growth Council’s annual Measures of Growth report. While other states increase their value-added per worker, Maine’s has remained relatively flat. Maine’s average of $88,795 per worker in 2013 was 24 percent below the national average of $117,472 and 28 percent below the New England average of $123,909. In 2007, the value-added per worker was 25 percent below the national average.

“The value added to products by workers depends on many factors, including the makeup of our industrial base, the skills and education of our workforce, the costs associated with doing business, and our infrastructure,” wrote the authors of 2015 Measures of Growth, published in April. “There is no single action we can take, no single lever we can pull, that will improve the value added of Maine workers.”

The council has set a goal that Maine’s productivity measure will improve to within 15 percent of the national average by 2020.

The wage growth slowdown is obviously bad news for workers with stagnant paychecks – but it also has implications for monetary policy.

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen has said in the past that wages should be growing faster, even given the pace of productivity growth and 2 percent inflation. Still, she and other Fed officials have stressed that a pickup in pay isn’t a precondition for their first interest rate increase since 2006.

The Fed has also been less vocal in emphasizing wages as a yardstick for labor market improvement recently. That could signal that they’re coming to terms with a new reality, Stanley said.

“We’ve gotten reflexively used to viewing the 2 percent trend in labor costs in the past six years as abnormally low, but is it?” Wieseman wrote in a July 31 research note. “Two percent is about where wage growth should be trending with zero percent productivity and a 2 percent inflation target.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.