A company that was at the center of a nationwide salmonella outbreak that sickened thousands and has had close ties to notorious Maine egg magnate Austin “Jack” DeCoster has purchased three Maine egg farms once owned by DeCoster.

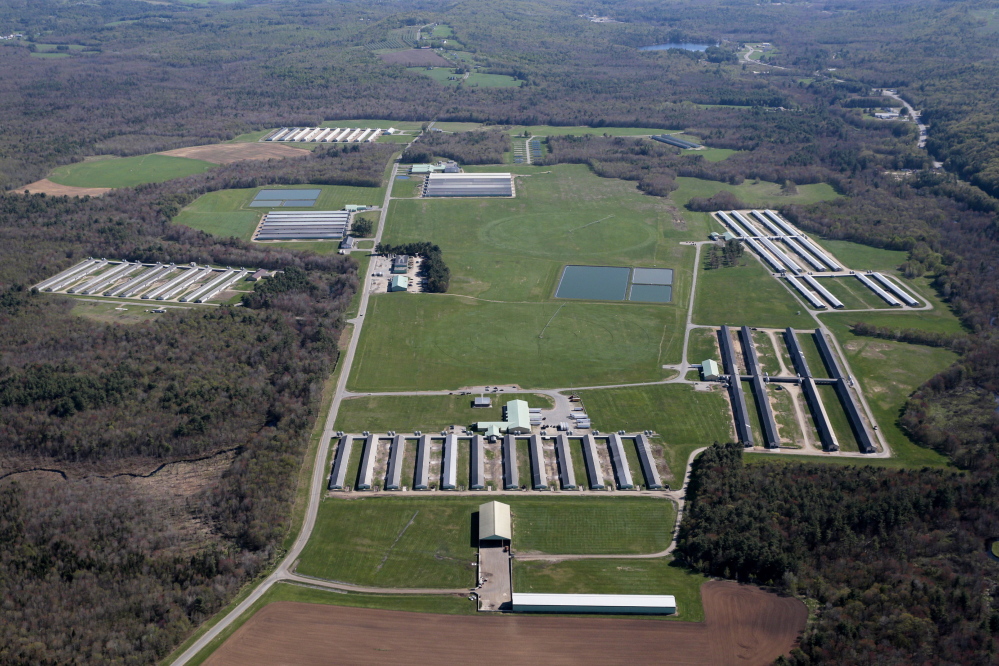

Pennsylvania-based Hillandale Farms, operating through a subsidiary, purchased the farms in Turner, Leeds and Winthrop from a subsidiary of Land O’Lakes, the Minnesota egg and dairy cooperative that acquired them in a lease deal in November 2011. Hillandale and its founder have longstanding ties with DeCoster, a serial rule-breaker who was sentenced in April to three months in jail for his role in the 2010 salmonella outbreak. Federal officials traced the outbreak to two Iowa farms, one controlled by Hillandale, the other by DeCoster and his son, Peter.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that the outbreak included 1,939 confirmed cases of salmonella, and that more than 56,000 people may have been sickened. It resulted in the recall of half a billion eggs, a high-profile congressional hearing, and ultimately federal charges against the DeCosters alleging they and their company knew their eggs were testing positive for the disease but did not try to divert eggs from the market.

Hillandale Farms, whose eggs are sold in supermarkets across the country, was founded by Orland Bethel, for years a close ally and business partner of Jack DeCoster, and he still serves as president of its primary unit, Hillandale Farms of Pennsylvania. Bethel also serves as secretary of Hillandale Farms East Inc., the parent entity of the integrated enterprise, which is headed by Orland’s son, Gary Bethel.

Orland Bethel, whose Iowa egg farm was forced to recall 170 million eggs in 2010, invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination to avoid testifying before Congress about the outbreak. The contaminated farm – doing business as Hillandale Farms of Iowa – bought eggs, young chickens and feed from the DeCosters’ Iowa egg farm and feed plant. DeCoster also was apparently an investor in the Iowa farm. A Hillandale spokesperson told The Wall Street Journal in 2010 that the farm and the DeCosters’ feed entity were “financially affiliated,” which allowed them to avoid state feed inspections.

In 2006, Bethel got in hot water with Ohio authorities when they discovered he was concealing the real owner of several troubled egg farms he managed there: DeCoster, who was prohibited from owning or operating egg farms in Ohio because he had already been labeled a “habitual offender” of environmental rules and regulations in Iowa.

DeCoster had invested more than $67 million in the Ohio company, Ohio Fresh Eggs, whereas other investors had put up only $10,000, Forbes later reported, making him the controlling owner. Ohio authorities tried to revoke the farms’ permits, but were ultimately prevented from doing so by a state review board. As recently as the summer of 2011, DeCoster continued to control Ohio Fresh, even though Bethel was the front man.

It is unclear whether DeCoster is still invested in the Hillandale companies or whether he is involved in the newly incorporated subsidiary that is buying the Maine farms, Hillandale Farms Conn LLC. Employees at Hillandale’s offices in Turner, and in North Versailles and Codorus, Pennsylvania, would not comment for this story, nor were they willing to provide a person who would.

OVER HALF A CENTURY OF MISCONDUCT

DeCoster, 81, is perhaps the most infamous businessman in Maine history. Over a half century of misconduct, his egg and hog companies have paid millions in fines and damages for everything from faking trucking logs and knowingly hiring illegal immigrants to environmental contamination, animal cruelty, workplace safety problems, and the exploitation of workers, including the alleged rapes of female employees by supervisors and the terrorizing of workers housed in squalid, crowded, cockroach-infested company trailers at his Maine farms.

In the 1970s, abuses at DeCoster’s farms prompted Maine legislators to pass laws forcing him to pay workers minimum wage and prohibiting children from being employed near hazardous machinery and substances. In 1988, New York banned the sale of his company’s eggs after a deadly salmonella outbreak, and three years later Maryland followed suit amid reports of piles of rotting birds at his farms on that state’s Eastern Shore.

New England’s major supermarket chains boycotted his eggs in 1996, after widespread abuse of Mexican and Mexican-American workers in Maine were revealed. The workers said they were treated like “slaves,” and then-U.S. Labor Secretary Robert Reich said conditions at the Turner facility were “as dangerous and oppressive as any sweatshop we’ve seen.”

In 1997, the company paid $2 million in connection with U.S. Labor Department charges of gross workplace safety violations. In 1998, it reached a $3.2 million settlement with the Mexican government for allegedly mistreating Mexican nationals based on race. In 2002, it paid $1.53 million to settle allegations that supervisors at its Iowa facilities had raped female employees and threatened to fire or kill them if they resisted.

In 2003, DeCoster was sentenced to five years’ probation for knowingly hiring 121 undocumented workers at his Iowa and Nebraska farms. Nonetheless, in 2006 and 2007, dozens of suspected illegal immigrants were arrested at his farms in Iowa, where state authorities already had labeled him a “habitual offender.”

Between 2002 and 2008, DeCoster’s Maine farms were fined more than $600,000 by the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration for repeated and serious violations, including exposed asbestos, unsanitary showers, hazardous equipment and disregard for workers’ safety. In 2009, DeCoster agreed to pay more than $125,000 in penalties and fees after undercover animal cruelty activists videotaped live hens being tossed into trash cans at the Turner farms to slowly suffocate under dead birds.

MAINE REVIEWS NEW ENTITY’S PERMITS

Relations between DeCoster and Bethel may have soured in the aftermath of the 2010 salmonella outbreak. That August, as federal investigators were moving on his Iowa facilities with search warrants, Bethel wrote a manager: “We have been told by Costco and Walmart that they will not be doing any business if Jack and his people have any involvement in management.”

“Hillandale needs to totally disassociate itself from Jack and it has to be real,” Bethel wrote in a follow-up email the next day, later disclosed in legal proceedings.

DeCoster sold his Maine operations to a subsidiary of Land O’Lakes in a November 2011 lease-to-purchase agreement, but his legal problems weren’t over. In October 2013, he settled a discrimination suit by Homero Ramirez, his longtime plant manager, for an undisclosed sum. Ramirez alleged that he had worked for 22 years in “an environment and culture that treats Mexican-American workers as ‘stupid’ and virtual slaves whose only value is their willingness to perform dangerous or demeaning tasks for DeCoster,” according to his civil complaint.

Land O’Lakes sold the farms in early July, according to an article that ran in the Sun Journal newspaper later that month, citing Maine Department of Agriculture officials. The paper did not establish the connections to DeCoster or the salmonella outbreak.

The Maine Department of Environmental Protection would have to approve transfer of the farms’ permits to Hillandale Farms Conn LLC. Department spokesman David Madore said by email that it received the application this week, but he could not predict when its review would be complete.

Corporate filings in Maine show the new Hillandale entity’s secretary is Syed Rizvi, who is general manager of Hillandale’s operations in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Rizvi was not available for comment, and another official who would not give his name declined to answer questions. “I’d rather not comment on that or on anything,” he said.

Land O’Lakes spokeswoman Rebecca Lentz said the company would not comment either. “We don’t have any information to share,” she wrote in an email.

The Minneapolis Star-Tribune reported in April 2014 that the company was divesting itself of all egg production operations because they had been losing money.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.