Stephanie Gebo knew her boyfriend, Robert Burton, had a rough past and had kidnapped another one of his ex-girlfriends and spent a decade in prison on domestic violence charges.

But she was a person who liked to help and thought she could help Burton.

The two dated for about two years, and by the time they broke up in late May, Vance Ginn said he and his wife, Angel, knew little about the relationship and saw less of Gebo — their daughter — and her children.

The night before she was killed, Gebo, in a phone call with her stepmother, said she would tell her the details of the breakup soon.

Angel Ginn, Gebo’s stepmother, asked her, “Do you think (Burton) learned his lesson last time?”

Vance Ginn said that Stephanie said, “‘Oh no, I don’t think he did.'”

Ginn, in an interview Friday, said his daughter didn’t have a protection-from-abuse or restraining order, and that even if she had, he doesn’t think it would have done anything to protect her from Burton, who police say shot his former girlfriend to death on June 5. Gebo’s bloodied body was discovered the next morning by her 13-year-old daughter and her 10-year-old son.

Ginn said he believes that if Gebo had left her house rather than having Burton leave when they broke up, she would have been safer. A police affidavit says Gebo changed the locks on her house after the breakup and slept with a gun by her bed.

Looking back, Ginn says the separation between their daughter and themselves may have been a sign of an abusive relationship that eventually ended with Gebo’s death. Burton had been on probation for a conviction on multiple felonies, but that probation ended June 4.

Medical Examiner Margaret Greenwald, who conducted the autopsy on Gebo’s body June 7, found multiple gunshot wounds to the lungs, spinal area and trachea and determined the death was a homicide.

“We had a pretty constant relationship with Stephanie, and then as time went on with Rob, we saw less and less of her, and less and less of the kids,” Ginn said Friday. “We didn’t recognize it, sadly.”

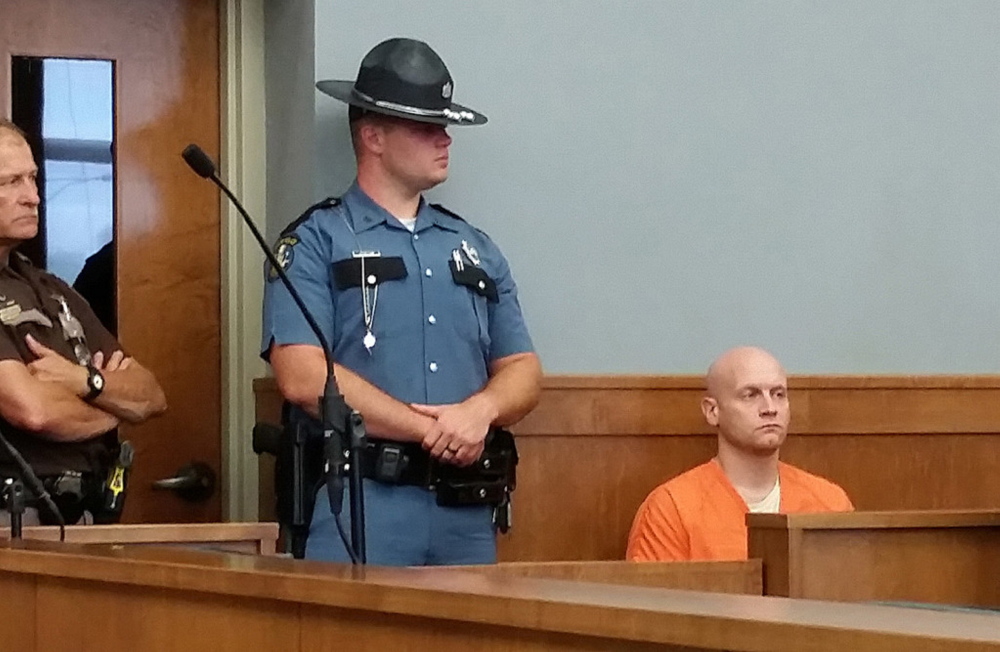

Burton, 38, who turned himself in to police earlier this week after a nine-week manhunt in Piscataquis and Somerset counties, is in custody on a charge of being a fugitive from justice and is a suspect in Gebo’s slaying.

Every domestic violence relationship looks different, and while the overarching issue might be the same — that one partner is exerting too much control over the other person — it can be hard to pinpoint the characteristics of an abusive relationship, said Margo Batsie, justice systems coordinator for the Maine Coalition to End Domestic Violence.

“A lot of times I tell people to trust their gut,” Batsie said Friday. “If you think something is going on, it’s OK to ask the person you care about or to call and talk to an advocate if you’re not sure what to do.”

Burton has a lengthy criminal record that includes spending more than 10 years in prison for domestic violence. He was convicted on three domestic violence charges in 2000 when he threatened to kill a woman who broke up with him, Piscataquis County District Attorney R. Christopher Almy told the Bangor Daily News in June.

Almy said after Burton was released in 2002 following service of a prison term on multiple convictions, he threatened and assaulted his victim’s mother. After a two-week manhunt and a four-hour standoff, he gave himself up to police and was sentenced to 10 years on multiple charges. Almy said he was released in June 2011, and four years of probation ended June 4.

An affidavit released at Burton’s court appearance Wednesday told a chilling story of Gebo and Burton’s relationship, his anger and her fear for herself and her children.

A man described as a lifelong friend of Burton’s told police that when he spoke with him before Gebo was killed, Burton had talked about breaking up with her and he suspected she had cheated on him.

He told the friend, “It ain’t over yet.”

The friend told Burton to not do “anything stupid with Steph,” to which Burton said not to worry — he was just mad at Gebo, according to the affidavit.

Another friend told police that Burton once said that if he has problems with a woman again, “he is going to kill her.”

Both children told police that “Robert is not supposed to have guns; that Robert has a lot of guns; that he has pistols, rifles and shotguns,” according to the affidavit.

By the end of Gebo and Burton’s relationship, Ginn said he knew hardly anything about his daughter’s relationship with Burton.

Gebo’s children told police told that Burton was “always angry” and had accused her of cheating. They broke up just about a week before he allegedly broke into her house and shot her. To protect herself, Gebo slept with a gun next to her pillow and changed the locks on her doors.

Ginn said he hopes his daughter’s death can bring more attention to some of the signs that family members can look for if they suspect a loved one is in an abusive relationship — things such as increasing separation from family and friends, not wanting to do things outside the house or wanting to keep everyone in the family at home.

Ginn said he believes that Burton tried to control his daughter, a trait that led to accusations that she was cheating on him.

“That’s what Rob did with the first girl that he kidnapped and the same thing he accused my daughter of,” Ginn said. “It’s something he tried to build in her head, and then he lashed out.”

Not every accusation of cheating is an indication of an abusive relationship, Batsie said, and it can be hard for family and friends to notice.

“For family and friends it can be really difficult, because there may not be any outward signs, which is why we really try and reach the actual victim. No one can really know that you need help in a relationship if you don’t think you do,” she said.

“Go someplace,” Ginn said Friday. “I don’t care about if it’s your place of residence or not. Go someplace, whether it’s your parents or some protective housing; but get out. Don’t try to make them get out. You get out. Because if you try and make them get out, this is what happens.”

But for many victims of abuse, leaving stable housing is not easy, Batsie said.

“For the vast majority of people, the problem of housing is so great,” she said. “Does she have a job? Are her kids in a school system? You can’t just disappear anymore. We need a way to keep people safe in their homes.”

Rachel Ohm — 612-2368

Twitter: @rachel_ohm

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.