AUGUSTA — An increasing number of children are hungry and homeless in Augusta, and about 50 area municipal and school officials, social service agency representatives, church leaders and others came together Tuesday to begin to try to figure out why and what can be done about it.

One question that came up at the community forum on childhood hunger and homelessness was whether the children and families who are at least at times going without enough food or adequate shelter are from Augusta or are coming to the city to seek help.

Advocates and service providers said it is both and warned against stereotyping people in need of help, because they’re just as likely to be your neighbors as someone “from away.”

Kimberly Martin, chairwoman of the school board who said she works with her church, which has a food pantry and other outreach programs, said, “I can tell you, being the person that answers the phone (when people call for help), most of the people are right here in the community. They’re sitting next to you in the pew. People are struggling. They’re losing jobs. There are substance abuse problems. … Yes, some come from away, but many families from here are struggling.”

Abigail Perry, outgoing executive director of the Augusta Food Bank, asked why should it matter where they come from.

Mayor David Rollins, who prompted that part of the discussion by asking the crowd where most of the people in need were coming from, said his point wasn’t that the community shouldn’t help people who aren’t from the area; it should, he said. Rather, he said, he’s concerned Augusta’s image could suffer when a problem that is widespread in the state and country is focused upon as an Augusta problem, not a larger problem. And he said higher-than-average rates of poverty and qualification for free and reduced-price lunch programs in the schools could be skewed by people coming into Augusta looking for help because it is a service center.

“The point is the image of the city of Augusta is something we should all be concerned about,” Rollins said. “And the story that goes out should be accurate and clear. I’m not here to promote a false reality. But I get the impression sometimes, when I hear about it and see it in the press, I think we get a bad rap.”

Robin Miller, who works for the Family Violence Project in its domestic violence shelter, said the shelter, when it gets calls on its help line from domestic violence victims from out of state seeking to come to the shelter, encourages them to work with domestic violence agencies in their own state. She said families are generally better off remaining in the state where they live, in part because they might have family support there. She said the only people they accept from out of state are victims who have ties to or relatives in Maine.

At-Large City Councilor Dale McCormick said a Maine Women’s Policy Center study 10 years ago found people on welfare were not coming to Maine at a higher rate than people not on welfare.

“They found no, people were not flooding into Maine because welfare policies were liberal,” McCormick said. “They were coming and going at an equal rate, for the same reasons you and I would move in or out of state. Low-income people are just like the rest of us, and they’re moved by the same things.”

According to Theresa Violette, homeless liaison and Title I director for Augusta schools, last year 101 students were identified as homeless in the city’s schools. Of those, 27 lived in a shelter, nine were in a hotel, 15 were unaccompanied by their guardian and 65 were “doubled up,” meaning they were living with other relatives or friends. She said that number has increased every year since she started doing that kind of work four years ago.

Superintendent James Anastasio said the number of students not quite meeting the criteria to be considered homeless by federal standards is larger than the number who do. He said, for example, Augusta gets a number of students whose families lose their housing in neighboring communities and come into Augusta to live with relatives. Those might not show up in the “homeless” statistics, he said.

In general, he said, students who come to school from a less-than-stable home environment and are hungry struggle to do their best in school. He said that doesn’t mean they can’t be successful, but that there are more obstacles to them succeeding.

Violette also said she’s seen a pattern of a growing number of students on Monday mornings saying they are hungry because they hadn’t had a meal over the weekend.

The school system has about 2,300 students.

The percentages of Augusta students eligible last year to receive free or reduced-price lunches at their respective schools, because their families have incomes low enough to qualify, were these: Cony, 52 percent; Farrington, 60 percent; Hussey, 52 percent; Lincoln, 70 percent; and Gilbert, 65 percent.

At Bread of Life Ministries’ homeless shelter in Augusta, which officials have said is frequently full, more than 60 percent of the people who stay there are families, and 1 of every 3 people there is a child, according to the nonprofit organization’s website.

Ward 2 City Councilor Darek Grant said groups such as Augusta Food Bank, Bread of Life Ministries, United Way, church organizations, schools and others are working to address both youth hunger and homelessness, but despite those efforts, there are still Augusta children going without adequate food or without a place to call home.

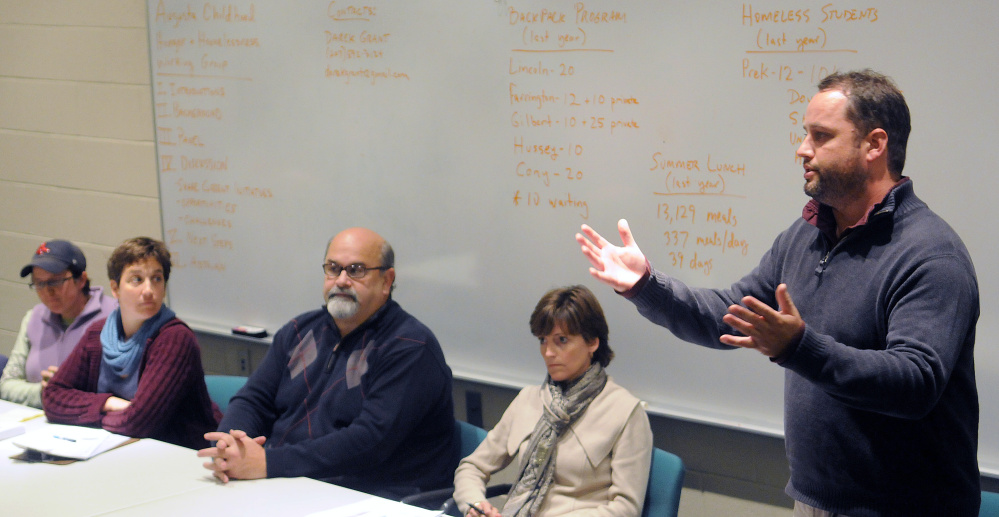

That’s why he proposed the creation of the working group to seek to address childhood hunger and homelessness. The Augusta City Council unanimously supported the creation of the group, and its first meeting took place Tuesday at Augusta City Center.

Grant said an important early task will be to identify who and what organizations already are working on those issues and who wants to be involved in the working group’s mission. Several leaders of groups working to combat hunger and homelessness briefly described their organizations and efforts to help children Tuesday.

Perry, for example, said the Augusta Food Bank’s Kids Packs program, which provides school-age children with bags of easily-prepared health foods over the summer and on school vacations, started in 2008, and the program has given out more than 6,300 packs since then.

She said the food bank serves 15 percent of the city’s population.

Sue Daniels, from Southern Kennebec Child Development Corp., a nonprofit that operates Head Start and child care facilities in the area, said her group, too, sees a large number of babies, up to age 5, who are homeless. She said last year 49 families were identified as homeless among their clients.

She said one family with five children, each of them with a disability, lived at the shelter and, because the shelter closes during the day, would sit in their van together until the warming shelter in Augusta opened for the day.

“There is a big need out there,” Daniels said. “They’re here.”

Other speakers said causes of childhood hunger and homelessness include the cost of housing, the difficulty of getting to work among people who can’t afford cars, the cost of child care and low wages.

Keith Edwards — 621-5647

Twitter: @kedwardskj

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.