AUGUSTA — Logan Parker looked high while Hallee Pottle looked low, scanning the ground, peering into thick bushes, up tree trunks and through the treetops into the sky, and listening for telltale chirps, tweets, and squawks — on the hunt for birds to add them to their logbook, not dinner plates.

The couple joined nearly 30 other local residents Saturday in searching for and counting birds in a 15-mile-diameter circle, centered around the State House, as part of the National Audubon Society’s annual Christmas Bird Count, the longest-running citizen science survey.

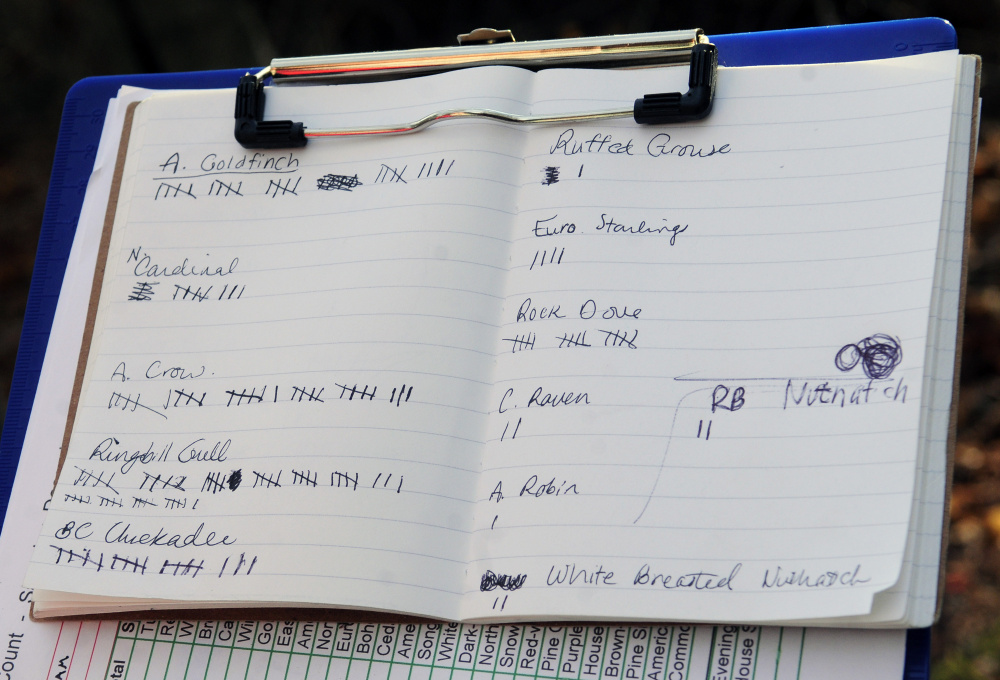

By 10 a.m., about halfway through their planned bird-counting for the day, the pair, who had been out since 7 a.m., had spotted 14 species, with the most common species being ring-billed gulls, crows, and black-capped chickadees, all of which were plentiful in their designated counting area. That included multiple east side neighborhoods between routes 3 and 17, including the area surrounding Cony High School.

Their assigned turf ran up to, but not over or into, the Kennebec River. Any birds over or on the river belonged to the group counting birds on the opposite, west side riverbank.

It was Parker and Pottle’s first Christmas Bird Count, but not their first time birding.

“I consider myself always birding,” said Parker, adding that over the last year, he has spotted 190 species of birds in Maine. “I enjoy it as a hobby and enjoy contributing to the research.”

Among the more rare bird sightings on his “Maine list” this year was a Ross’s goose that birders have been flocking to see in Westbrook, an unusual sight here because Maine is generally well out of the white bird’s range.

Parker, of Augusta, and Pottle, of Palermo, also have participated in other citizen science projects, collecting data on bats as part of a state Inland Fisheries and Wildlife project, as well as frogs. On Sunday, they plan to count birds again, for a similar Audubon Christmas Bird Count focused on the Waterville area.

Halfway through the counting Saturday, species they spotted beyond the dozens of gulls and chickadees included a pair of snow buntings flying over the Ballard Center alongside the Kennebec River, a couple of ravens, and a ruffed grouse that took flight as they searched for birds along the riverfront.

“That was kind of cool. That’s not a bird you see often in the city,” Parker said.

Pottle, Parker said, is usually the first to see birds; while Parker, Pottle said, is better at identifying them.

“I like the challenge. I like to be the one to spot something first,” Pottle said about birding. “And I love the community. You can go somewhere and there will be three other birders there with scopes out, and they’ll all be gushing about the same thing. It’s a lifestyle for a lot of people.”

At the end of the day, the 14 teams of counters convened at Viles Arboretum to tally up their totals.

Last year, the Augusta Christmas Bird Count counted a total of 53 species and 6,389 individual birds, according to Cheryl Ring, of Augusta, an organizer of the local event. Among those birds were 17 bald eagles, 791 rock pigeons, 18 pileated woodpeckers, 30 eastern bluebirds, two northern mockingbirds, 944 European starlings, 120 northern cardinals and 140 house sparrows.

In 2013 the Augusta count tallied 48 species.

Since the Augusta count started, in 1970, more than 250,000 birds have been counted, with an average of 45 species a year spotted over those years.

Each year about 72,000 volunteers participate in the bird count, which began in 1900 when Frank Chapman, founder of Bird-Lore, which later became Audubon magazine, suggested an alternative to a holiday bird hunting tradition in which teams competed to see who could shoot the most birds.

“He suggested counting, instead of killing, birds might be a bit more sustainable,” Parker said of the start of the bird count.

The masses of data collected allow researchers to track trends in bird populations and how birds are responding to a changing climate.

Parker and Pottle came equipped with a smartphone loaded with a recording, provided by Audubon, of a flock of chickadees scolding a pygmy owl. When they played it, chickadees emerged from the surrounding woods, attracted to the sound. And once the vocal chickadees showed up and raised a commotion, other species started to show up, too, including white-breasted nuthatches and a tufted titmouse.

“It kind of drives the birds nuts. Chickadees hear it and try to join up. It’s a defense strategy for them,” Parker said. “And once you draw in chickadees, other birds show up, because they’re so vocal.”

He recommended against using that method when birds are nesting, to avoid disturbing them.

Parker also used a technique called pishing, in which he makes a sound kind of like “pishhh, pishhh,” to draw in birds so they can be identified.

They searched both on foot, such as along nature trails around Cony High School and on the riverfront; and by car, scanning bird feeders in residential neighborhoods.

Keith Edwards — 621-5647

Twitter: @kedwardskj

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.