BENTON — Catching a glimpse of a bald eagle 30 years ago would have been an experience to savor. The large raptors, well-known American national symbols, were just coming back from the brink of extinction. Contamination from a pesticide, loss of habitat, and hunting had reduced the number of eagles to fewer than 500 nationwide in the early 1960s.

Seeing one bird, let alone a nesting pair, would have been rare. But thanks to special legal protections and a national recovery, bald eagles are thriving again.

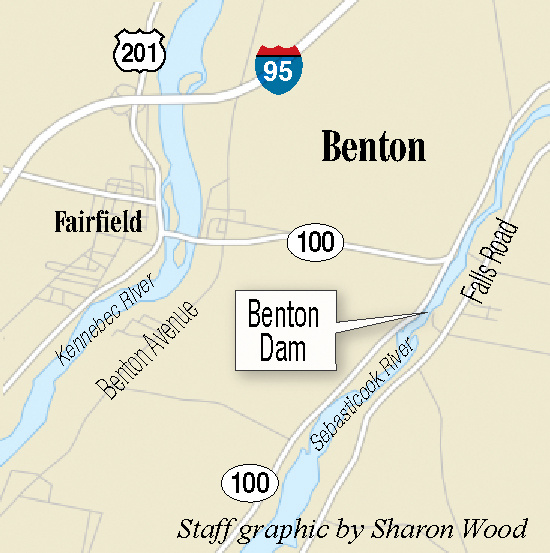

One need only visit the banks of the lower Sebasticook River in Benton during the annual alewife run in mid-spring. The fish migrate in the millions from the Gulf of Maine north up the Kennebec and Sebasticook rivers to spawning grounds in lakes and ponds farther north.

During the run, dozens of eagles descend on the river, feasting on the easily-available fish and loading up after a lean winter. Researchers regularly document 40 to 50 eagles at a time in a 5-mile stretch of the Sebasticook from the former Halifax Dam site in Winslow to the functioning Benton Falls Dam in Benton.

On a mid-June day two years ago, observers recorded 64 eagles along the central Maine corridor, believed to be the largest aggregation of bald eagles recorded in New England. Those results came from a joint study of the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife and the Biodiversity Research Institute, a Portland-based nonprofit focused on studying wildlife and the environment.

For comparison, researchers estimate there were fewer than 30 breeding pairs of bald eagles in the entire state in the early 1970s.

The 2014 research was the first phase of a years-long effort to track the number of bald eagles on the Sebasticook and what effect the restored alewife fishery may have on the long-term survival of the species. The Maine wildlife department is sponsoring a long-term monitoring project on the Sebasticook with volunteer citizen scientists.

Specifically, researchers are focused on how the alewife run could contribute to the survival of young, nonbreeding eagles, regarded as a buffer population between adults and very young birds.

That reflects a paradigm shift in addressing the bald eagle population, said Chris DeSorbo, a wildlife biologist with the research institute. Early restoration efforts focused on protecting nesting sites and young chicks. With eagles’ strong recovery — the raptors were taken off the federal endangered species list in 2007 and de-listed in Maine in 2009 — the attention is shifting to protecting important habitats for eagles, not just nest sites, DeSorbo said.

“One of the overarching themes of this effort is that seasonally abundant food resources are important to these populations and their sustainability,” DeSorbo said. “That’s where the alewives come in.”

Although bald eagles have recovered nationwide, the Sebasticook is a unique resource, DeSorbo said. The annual run of alewives and blueback herring, believed to be the largest run on the East Coast, was the result of a decades-long restoration effort of its own. That included removing dams and installing a fish elevator at Benton Falls in 2006, allowing fish to travel up the river to spawning areas. As a result, the run of alewives has increased.

An immediate population rebound followed — now an estimated 3 million fish traveling up the waterway, up from fewer than 50,000 a decade ago. That’s had an environmental ripple effect: A commercial fishery has started to take advantage of the resource to use as bait, and alewives also might help improve water quality in impaired lakes and ponds.

Alewives also have a direct effect on biodiversity in the area. The little fish are near the bottom of the food chain and are preyed on by virtually every predator.

For bald eagles, the alewife run may present a uniquely valuable resource, DeSorbo said. The alewife run coincides with the eagle’s breeding season. The fish probably aren’t that important for nesting pairs, but it is important for young, nonbreeding eagles and sub-adults, which are eagles less than 5 years old, DeSorbo said.

Those young birds travel long distances but can be blocked out of habitat and food resources by nesting adults that fiercely defend their territory, he explained.

“There is a lot of areas in the state they can’t really go. If a sub-adult wanders into another eagle’s territory, especially a breeding eagle, they will be chased out,” DeSorbo said.

Areas with high food abundance, like the alewife run, may limit territorial impulses, simply because so much is food available. That means young adults can camp out in the area for months and eat their fill without infringing on the sensitive territory of a nesting pair, DeSorbo said.

Sub-adult eagles have a high mortality rate and are generally more vulnerable than mature adult eagles, so the alewives could give some young adults a leg up and improve their chances of survival. According to the results of the 2014 study, eagles frequented the alewife run from mid-May to early July.

“The daily counts of eagles using the Sebasticook River may translate to use by hundreds of eagles over the course of the year,” researchers said a report on the study released last year.

The concentration of eagles didn’t line up directly with the time of the gigantic upstream migration, but eagles were likely preying on the fish as they came downstream back to the ocean after spawning, DeSorbo said.

The connection between alewife restoration and a healthy, stable bald eagle population could bring attention to what an important resource the Sebasticook River is, and the need to preserve it, he added.

“They are related,” DeSorbo said. “People may not get excited to talk about fish. When you bring this kind of charismatic predator into the discussion, it really puts a face on the issue of environmental protection.

“Areas like this need to be studied and documented for the ecological resource they are, and then we need to talk about what we need to do to protect it.”

Peter McGuire — 861-9239

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.