When 500 people swarmed Monument Square on the evening of July 8 to protest the fatal shooting of two black men by police in Louisiana and Minnesota, the young man at the head of the crowd holding the microphone was trying out a new life calling.

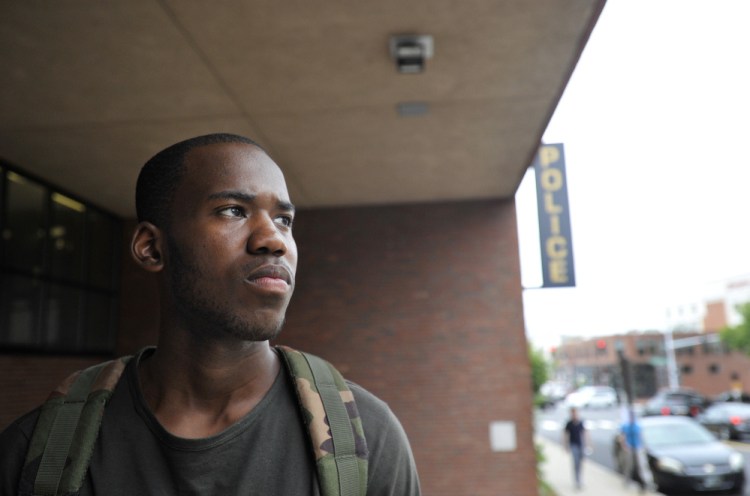

David Thete, 18, had never organized a public event in his life, but in the wake of those killings and the shooting deaths of five Dallas police officers just days later, Thete and the small organization for teenagers he founded were suddenly at the center of a public conversation about race and policing.

“It started out small,” Thete said of his fledgling group. “We just wanted it to be young kids. And then we made a Facebook page, and adults started sharing the page. It went from 50 people to 100 people to 300 people.”

Soon the Portland branch of the NAACP got involved in his planned march; permits were obtained, police were alerted. Thete, along with a representative from the NAACP, met with police for hours before the march, which then went off without a hitch.

Kesho Wazo, the loose affiliation of about 30 teenagers that Thete had founded in February, had made its first major public foray.

David Thete, 18, speaks during the vigil July 8 in Portland to remember Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, black men who were killed by police in Louisiana and Minnesota. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

“I thought it was a highly successful event,” said Portland Police Chief Michael Sauschuck. “Everyone was very passionate and engaged in the issue, and I think that speaks to the character of the people of Portland.”

The cooperative nature of Thete’s march contrasted with another protest held a week later, last Friday, by another group, the Portland Racial Justice Congress. Members of the group took to the streets to protest incidents of police brutality without first giving notice to police or city officials. They stood arm-in-arm across Commercial Street in the Old Port for hours until police arrested 18 people for blocking traffic.

The July 8 event was a coming-of-age moment for Thete, who graduated from Cheverus High School in June. Since he was a pre-teen, Thete thought basketball would be the key to his future. But after failing to make the starting lineup and spending most games on the bench, Thete re-evaluated his priorities. He started Kesho Wazo because he was frustrated that he was not living the values of public service that his family instilled in him.

SHARED IMMIGRANT EXPERIENCES

Kesho Wazo means “tomorrow’s ideas” in Swahili, and was designed to be an outlet for his peers to explore their creativity through art, music and social advocacy. The group, which is still in its infancy, is made up mainly of Thete’s friends. Its mission and goals are nebulous but admirable – give young people a platform all their own, and let them do with it what they want.

“Grown-ups don’t really talk to youth,” said Thete’s mother, Adele Masengo Ngoy, 51. “We want to tell them what to do, but we don’t want to listen to them.”

Although still loosely organized, the group has attracted other young immigrants, many from African nations, who are grappling with the same issues of race and identity as Thete, whose family fled civil war in the Congo in 2000. Like many African immigrants who resettled in Portland, Thete’s family came to Maine after spending time in a refugee camp. He was 2 years old when he arrived.

Thete and his sisters have been fortunate with their educations – they have always attended private schools. It was a financial burden for his mother, but a decision that gave him greater opportunities.

The private school setting also made Thete painfully aware of his blackness at times, more so perhaps than if he had attended Portland public schools, which have a greater percentage of non-white immigrants.

Since middle school, Thete said he has been one of a very small number of minority students in his class and grade level. He recalled that in seventh grade, he was one of only two black students, and felt people were always staring at him.

“I always felt like an alien, like I didn’t fit in,” Thete said. “That was a culture shock to me.”

He felt too white for his black friends, and too black for his white friends, he said.

AFTER FAILURES, A NEW DIRECTION

The cultural implications of his race, while always apparent to his mother, became clear for Thete in 2012 after the shooting of teenager Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida. Thete saw himself in Martin: A young man, strolling home, snacking on a bag of Skittles.

The prospect terrified his mother.

One night shortly after Martin’s death, Thete said he was walking home through East Bayside, a hood pulled over his head, when his mother pulled up next to him in her car. She scolded him for his dress and told him he needed to be more conscious of how the world sees him.

Representatives of Kesho Wazo and the Portland branch of the NAACP met with police for hours before the march, which then went off without a hitch. “I thought it was a highly successful event,” said Police Chief Michael Sauschuck. Photo by Dylan Greenlaw

Her instructions were clear: When he spent time with his white friends, he needed to be careful. When he was with his black friends, he had to be even more careful.

In middle school, his passion for basketball caught the attention of the Cheverus boys’ basketball coach, and after some last-minute financial aid wrangling, Thete was enrolled.

In his freshman year at Cheverus, he was elected class president. He was well-liked and won attention from upperclassmen, but his grades began to suffer.

A dream of playing varsity basketball for the private high school evaporated when he failed four classes that year. By his junior year, after spending more time on the bench, he realized that basketball would likely not be the avenue of opportunity for him.

He started to get serious about school, and attended two leadership conferences focused on social justice. Now he plans to take a gap year before college so he can do community service work in Brazil.

“My mistakes have definitely made me,” Thete said. “Without failing those classes I wouldn’t have been as motivated as I am now.”

In the future, Thete hopes to see Kesho Wazo grow and find a foothold in the city, so more young people can connect with each other and find their voice in the community.

“Our mission is to empower young minds to show that you don’t have to fit into society’s norms,” he said. “You have to be yourself.”

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.