A new study questions the value of mammograms for breast cancer screening. It concludes that a woman is more likely to be diagnosed with a small tumor that is not destined to grow than she is to have a true problem spotted early.

The work could further shift the balance of whether screening’s harms outweigh its benefits. Screening is only worthwhile if it finds cancers that would kill, and if treating them early improves survival versus treating when or if they ever cause symptoms. Treatment has improved so much over the years that detecting cancer early has become less important.

Mammograms do catch some deadly cancers and save lives. But they also find many early cancers that are not destined to grow or spread and become a health threat. There is no good way to tell which ones will, so many women get treatments they don’t really need. It’s a twin problem: overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Whether to have a mammogram “is a close call, a value judgment,” said study leader Dr. H. Gilbert Welch of Dartmouth Medical School. “This is a choice and it’s really important that women understand both sides of the story, the benefits and harms.”

Welch has long argued that mammograms are overrated, and the study parallels work he published from the same data sources four years ago. This time, the authors include Dr. Barnett Kramer, a National Cancer Institute screening expert, although the conclusions are not an official position of the agency. The study was published Wednesday by the New England Journal of Medicine.

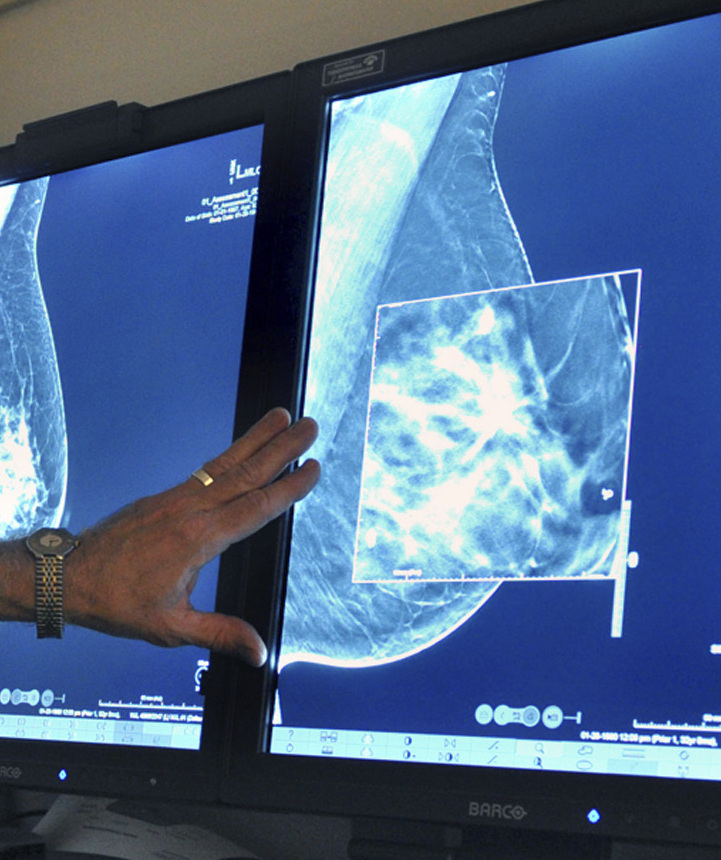

Researchers used decades of federal surveys on mammography and cancer registry statistics to track how many cancers were found when small, about three-fourths of an inch, versus large, when they are presumably more life-threatening.

They estimated death rates according to the size of tumors for two periods – 1975 through 1979, before mammograms were widely used, and for 2000 through 2002.

In the earlier period, one-third of cancers found were small. In the later period, two-thirds were small. But the change was mostly because screening led to so many more cancers being detected overall, and the vast majority of them were small – 162 more cases per 100,000 women, versus only 30 more cases of large tumors.

“The magnitude of the imbalance indicates that women were considerably more likely to have tumors that were overdiagnosed than to have earlier detection of a tumor that was destined to become large,” the authors write.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.