Joe McCarthy turns 30 on Saturday.

He doesn’t remember the day he was born, but the arrival of the flood baby is part of McCarthy family lore.

Five days earlier and nearly 2,000 miles away, a storm system whipped up over the Oklahoma panhandle that brought heavy snow to a large swath of the Midwest. It moved northeast, a cold front trailing behind. As the front passed over Virginia, an area of low pressure formed.

By the time the slow-moving system arrived in Maine, it was fat with rain.

The southeast wind that had been blowing pinned the system against the western mountains. The rain started early on Tuesday, March 31, and it didn’t end until sometime during the next day.

Joe McCarthy’s family lived on the west side of Augusta, and many of them could not get across the flooded Kennebec River to see him at the former Kennebec Valley Medical Center on Augusta’s east side.

With his personal connection to the 1987 flood, he chose that as a topic for a middle school presentation. That’s when his grandmother, Mary McCarthy to the world and Hully to friends and family, reminded him that she had been born during the 1936 flood.

Although no one could have planned it that way, two generations of the McCarthy family are linked by the two worst floods in Maine’s recorded history.

Technology and the ability to understand weather systems have improved immeasurably since 1987, as has the ability to issue warnings earlier.

But all the technology in the world cannot prevent another epic flood in the Kennebec River system. Experts say it’s not a question of if; it’s a question of when.

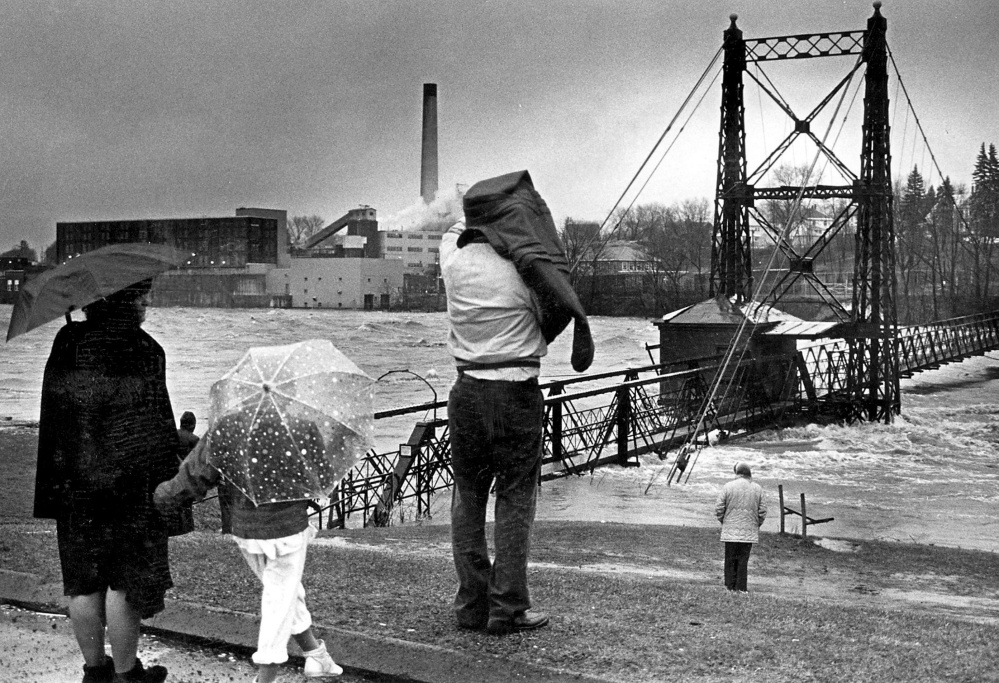

This file photo from the April 1987 flood shows Kennebec River running high at the Two Cent foot bridge between Waterville and Winslow.

THE BEGINNING

Don Hallenbeck walked his usual route from the apartment he shared with his mother at Westbranch Terrace along Main Street in Pittsfield to his volunteer job at the Pittsfield Public Library on Tuesday, March 31.

Pittsfield, like many Maine cities and towns, established itself on the banks of a river. For centuries, rivers have been used for transportation and trade, and when European settlement started in this part of New England, it followed the same pattern. As industry developed, rivers became a source of power for mills.

The Kennebec River, with a drainage area that spans nearly 6,000 square miles north of Merrymeeting Bay south of Richmond, has been the backbone of central Maine. It’s part of a system of rivers that links Somerset, Franklin and Kennebec counties by water.

The Sebasticook River, one of the Kennebec’s tributaries, flows through Pittsfield.

On that day, it was rising. By lunchtime, Hallenbeck detoured to Hartland Avenue to go home and return to the library, because Main Street wasn’t accessible.

The rain, he said, wasn’t so much hard as it was continuous.

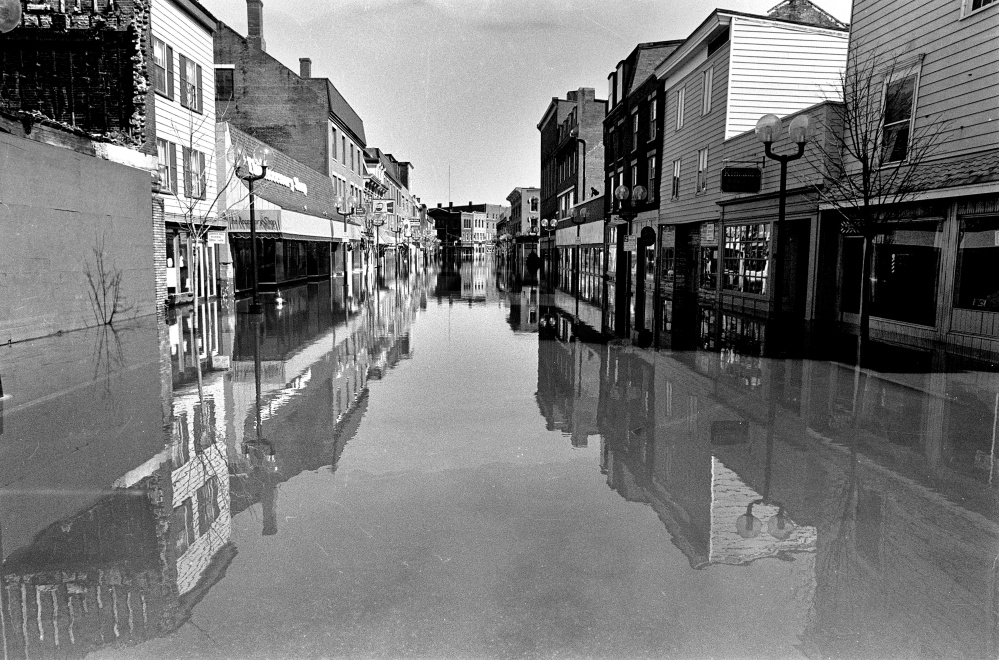

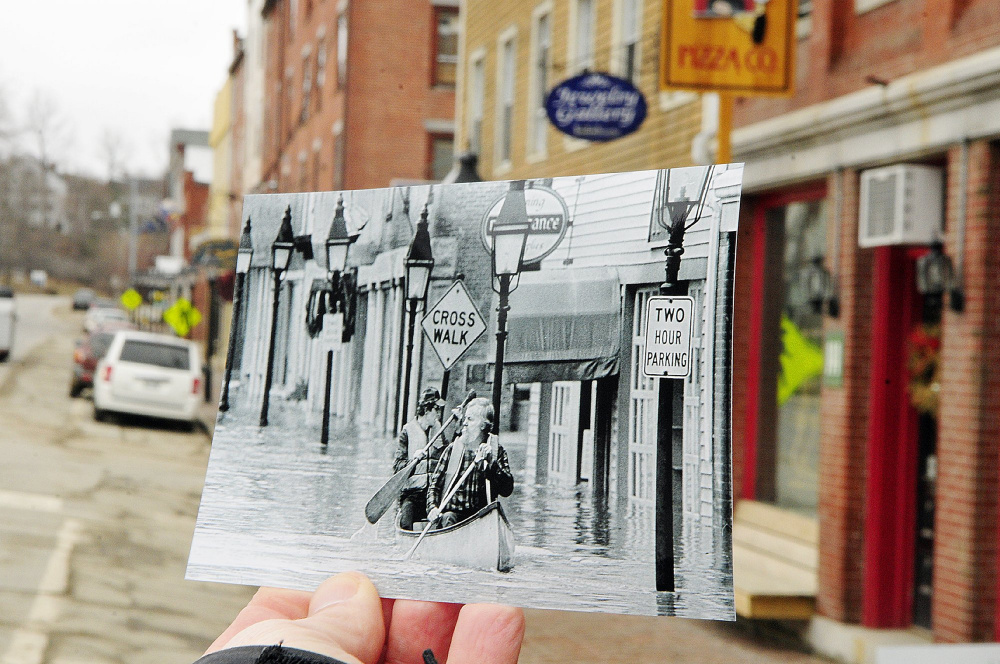

This April 1987 file photo Sumner “Sam” Webber, left, and John Jacques paddling a canoe on Water Street just past Central Street after the Kennebec River flooded downtown Hallowell.

“It was a spring freshet, like we had every year,” he said from his home in Pittsfield.

About 50 miles south in Gardiner, Logan Johnston was watching the rain and the Kennebec River. He had heard it was raining hard in the Carrabassett Valley, where the Dead River originates before it joins the Kennebec.

“I don’t know how water management works up there,” Logan Johnston said, “but the water was coming up hard the morning of the 31st.”

At the time, Johnston was in the Water Street building that housed Tilbury House Publishers, the business he founded. It was clear a flood was imminent, but no one knew how big a flood it would be.

Tilbury House offices were on the lower part of the sloping lot just south of the Gardiner Public Library, and the warehouse was on the upper part.

“The water was coming up fast enough that we moved our books from the first level of the warehouse to the upper level,” he said.

The rain continued to fall and the river continued to rise.

Things got a little crazy as people started to realize that conditions were worsening.

In a scene that was repeated along the river, store owners, business people, high school students and workers started to do what they could do — shift merchandise, equipment and belongings above the water’s reach.

THE MIDDLE

River floods in Maine tend to happen in the spring — usually because of some combination of ice break-up on the rivers, snowmelt and rain — and sometimes in the fall, when hurricanes roar up the East Coast.

Seasonal rises in river levels are common, and in some years, flood-prone areas in riverfront communities get wet.

By 1987, 51 years and two generations had passed since the last major flood.

In mid-March 1936, rain started falling as ice was breaking up on the Kennebec, and when it all started flowing, chunks of ice scoured everything they touched. Historic photos capture in black and white the damage to bridges in the Kennebec River system, including the bridge that linked Dresden and Richmond, torqued and twisted off its supports and carried downriver.

As the storm approached Maine in 1987, the National Weather Service issued its first weather statement at 2:30 p.m. March 30 for the St. John River in northern Aroostook County.

Tom Hawley arrived in Maine in 1989 to work as a National Weather Service hydrologist, when the weather service was still using Radio Shack TRS 80 computers.

“If you came here now, you’d wonder how we could ever get a forecast right before,” he said.

While Hawley didn’t witness the flood, the weather service’s files show how it unfolded.

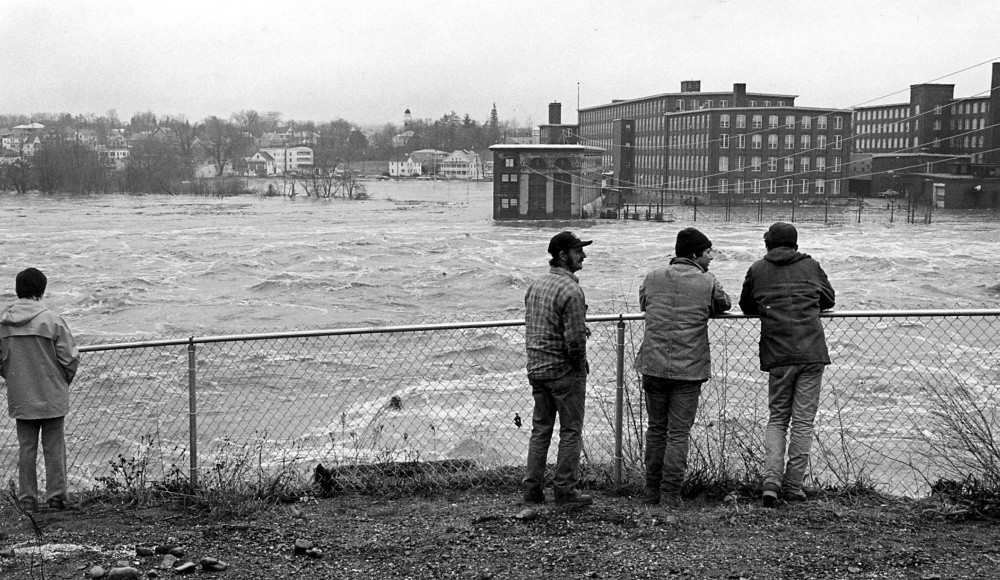

This file photo from April 1987 shows flooding in Skowhegan.

Observations included in reports completed by different agencies show the ice was already out on the Kennebec, and south of Skowhegan the snow had essentially disappeared, leaving the ground bare. The winter had been drier than usual with no January thaw.

The levels of the Moosehead, Flagstaff and Brassua lakes in the headwaters region of the Kennebec and its tributaries were at a seasonal low above their impoundment dams, leaving plenty of room for seasonal runoff that could be released over the course of the year for hydroelectric generation.

When the snowpack in the Kennebec headwaters area was measured in mid-March, Hawley said the snow-water equivalent was 6 to 8 inches. If all the snow were to melt in one day, it would produce as much water as 6 to 8 inches of rain.

The snowpack would have been deeper in the woods.

No measurement data is available for the end of March, but judging by the weather, Hawley said, the snowpack would have shrunk.

“The rivers would have been running higher than normal because of the snowmelt,” he said, “but there was not much ice, no ice jams.”

At 8:30 a.m. March 30, the National Weather Service issued a statewide flood watch. In National Weather Service parlance, a flood watch indicates conditions are favorable for a flood.

When the rain started falling early on March 31, it hadn’t reached the lakes and their available storage, and it was never going to.

It fell on a ripe snowpack, one that was ready to release its water. With spring only about 10 days old, the ground was still frozen, leaving runoff no place to go but into the channels of streams and rivers.

A flood warning, a notice that flooding is imminent, was issued at 2 p.m. March 31 for the St. John, Androscoggin, Piscataquis, Presumpscot and Kennebec rivers.

In Winslow, not far from where the Sebasticook met the Kennebec at Fort Halifax, a 9-year-old Tobias Parkhurst watched from the Oakes and Parkhurst building on Cushman Road.

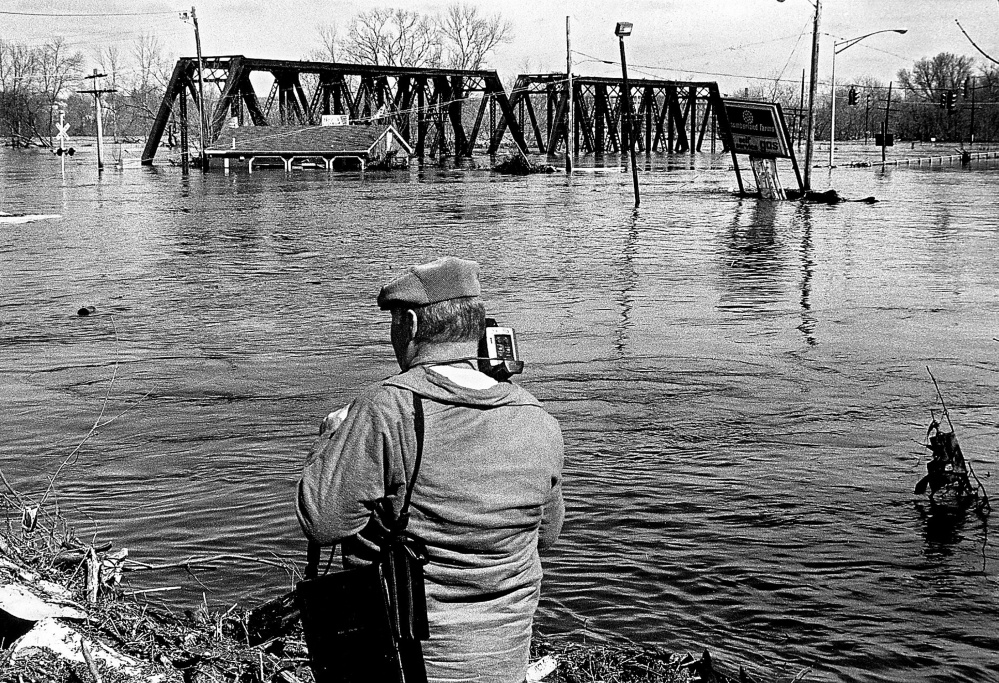

This photograph was taken of Bee’s Snack Bar in Winslow at the height of floodwater during the flood of 1987. The business survived the flood that swept away seven nearby homes on Lithgow Street.

“We were so high up on the hill, it felt like we were on a mountain,” Parkhurst said.

From that vantage point, he saw windows of the grocery store across the way shatter under the pressure of the water and the store’s stock start to float away.

“I have a very clear picture in my head of Bee’s diner disappearing. That’s the thing that struck me,” he said.

Bee’s Snack Bar sat 30 feet above the Sebasticook at the end of Lithgow Street. At the height of the flood, water reached the eaves of the restaurant.

The Parkhursts lived in Fairfield at the time and tried a number of bridges before they found one they could cross to get home that night.

By late afternoon, evacuations started.

In Pittsfield, Don Hallenbeck and his mother, Hazel, vacated their apartment with no time to pack. He stayed with a former landlord; she stayed with people she knew from her church.

The original Fort Halifax in Winslow was washed away in the flood of 1987. The fort was located just beyond the bridge next to Bee’s Diner, which survived the rising waters.

By Tuesday night, Gardiner residents were monitoring the rise of the Kennebec. That’s when the coal shed that had stood for years at the river’s edge behind the former railway station was lifted off its foundations and floated away.

“It was a classic coal shed. It was very long … and on the gable end someone had painted a Snoopy dog,” Johnston said. “I was standing with Donnie Cromwell, the recently retired public works guy, and it came over the radio that Snoopy was leaving the building.”

The Kennebec carried it to Richmond, where it broke apart against the bridge.

“The thing that was amazing about that night was that you could hear the Pearl Harbor Remembrance Bridge was humming,” he said. The force of the water caused it to vibrate.

At the height of the flood, an immense volume of water flowed through the river system. The U.S. Geological Survey maintains a river gauge at north Sidney in cooperation with the Maine Emergency Management Agency and the Maine River Flow Advisory Commission.

Two days ago, following a couple of days of light rain and snow flurries, the discharge rate was about 14,000 cubic feet per second.

Thirty years ago at the flood’s height, the discharge rate was 232,000 cubic feet per second.

“A basketball is about a cubic square foot,” Greg Stewart said. Stewart is the surface water hydrologic investigation chief for the USGS’s New England Water Science Center’s Maine office.

Imagine 232,000 basketballs passing that point every second; that’s how much water flowed.

Once the water started flowing, it was hard for the National Weather Service to catch up.

Hawley said at Augusta, the depth determined to be the start of flood stage was 13 feet.

“We forecast the flood at 17 feet, and it was twice that,” he said. “As time goes on and statements came out, we were chasing the flood.”

For every forecast, it seemed the river already had exceeded the prediction.

This file photo from the April 1987 flood shows an unidentified woman looking toward Water Street from the corner of Central and Second streets in Hallowell.

THE END

By sunrise on April 1, the rain was tapering off. In western Maine, Hawley said, it had turned to snow. The heaviest rain had fallen across New Hampshire’s White Mountains (8.3 inches) and in Maine around Blanchard (7.3 inches), but across the region, some areas received only a couple of inches.

“People probably woke up on the 31st not thinking there would be much of a problem,” Hawley said, “and woke up the following morning floating in water.”

In Augusta, then-Gov. John McKernan signed a disaster declaration that included all of Maine’s counties except Washington and Aroostook, where at the end of March the flood potential had been the highest.

The river crested at 34 feet in Augusta the following day, April 2, at 5 a.m., 17 feet about flood stage.

A week later, a second major storm pushed through the area, swelling the rivers in southern Maine, New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

In the end, the flood of 1987 was the largest in the state’s history to date.

Shawn Beckwith shovels out his grandmother’s mobile home during the 1987 flood.

The bill for damages was estimated at $100 million. Factoring in inflation, that would be more than $210 million today.

In Pittsfield, Don Hallenbeck was reunited with his mother. They landed with a relative in Clinton, while their belongings were stashed in several locations across town while work started on the ground-floor apartments in the complex. Hallenbeck said only a couple of inches of water got in, but the wallboard, insulation and carpeting had to be replaced just the same.

Their losses were minimal. They lost some kitchen supplies, the food in their freezer and a couple of books that had been knocked to the floor.

Other losses were broader.

The damage extended beyond the impact of the high-water levels. In its report, the USGS noted that water quality suffered throughout much of central Maine. Sewage treatment plants in the Anson-Madison area, Augusta, Farmington and Skowhegan were seriously damaged. For up to three months in some places, untreated sewage was discharged straight into the river.

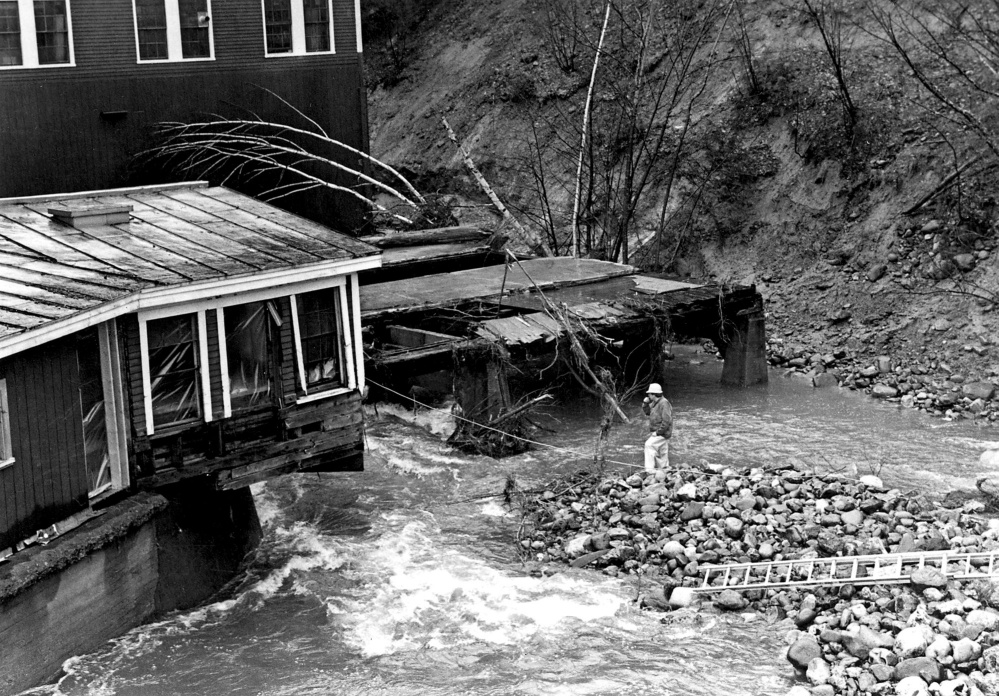

The Maine Emergency Management Agency reported that 2,100 homes were flooded; 240 sustained heavy damage and 215 were destroyed. Four hundred small businesses were affected. Roads were washed out and bridges were damaged or destroyed.

In Winslow, where dozens of houses were damaged, historic Fort Halifax, at the junction of the Sebasticook and Kennebec rivers, was swept away.

Also factored into the damage reports were the run-of-the-river dams that spanned the Kennebec to generate hydroelectric power.

Three decades ago, Peter Bragdon worked for Central Maine Power Co., when it owned the dams. He now works as the Kennebec River supervisor for Brookfield Renewable, which has acquired many of those dams.

Bragdon was dispatched from his duties on the Androscoggin River to complete a damage assessment of the dams in the Kennebec. It was, he said, millions of dollars.

“Mostly, the ’87 flood impacted the lower end of the river due to the unregulated Carrabassett and Sandy rivers,” Bragdon said. Those two rivers discharge into the Kennebec in the Madison area, and they brought flows up above the dams’ flood capacities.

Peter Bragdon, Kennebec River supervisor for Brookfield Renewable, shows how high the water came up inside the power house in Skowhegan during the 1987 flood.

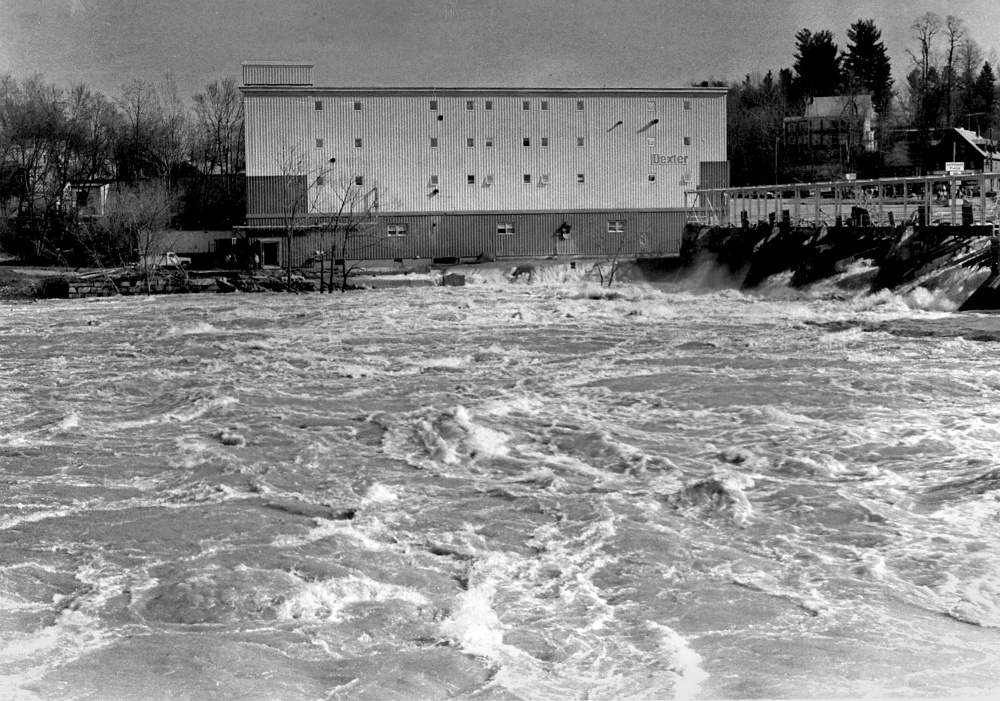

In Skowhegan, where the water crashed through town like storm-driven ocean surf, the Weston Station was nearly destroyed. Floodwater pounded against anything in its way — bridges, roads, buildings and the dam. It pushed through the facility’s upstream windows and pushed out the downstream windows. The station’s four-person crew and daily operator had been forced to evacuate after tripping the stanchion bays — essentially an abandon-ship protocol for dams.

“It’s a controlled means of passing water through the spillway,” he said. “You trip the beams and the wood that fills in the areas between the beams discharges into the river.”

That dam was breached, although the others were not. The dam structure had to be rebuilt where the embankments had washed out. In all the dams, the generators were out of commission, and it was months and millions of dollars before they were up and running again.

“It was quite the April Fool’s Day joke on us,” Bragdon said.

These dams, he said, were never meant for flood control, and they couldn’t have controlled the 1987 flood.

It was the flood of record for the Kennebec River.

The U.S. Geological survey calculates the size of floods based on the probability of a flood that size occurring within a time period, and it’s often misunderstood.

Many have branded the 1987 flood as a 500-year flood. That doesn’t mean the Kennebec region is safe for the next 470 years. Instead, it’s an expression of statistical probability that a flood of that magnitude will occur in any year.

Stewart, at the U.S. Geological Survey, said Richard Fontaine and Joseph Nielsen, who completed the report on the 1987 flood for the agency, calculated the annual exceedance probability at 0.01.

That, Stewart said, would be a 1,000-year flood.

THE NEW BEGINNING

“We missed it 30 years ago,” Hawley said.

This 2012 file photo shows Ryan Willette, left, and her mother Evelyn Willette standing outside their restaurant Bee’s Snack Bar beside the Sebasticook River in Winslow. The business narrowly escaped being swept away during the flood of 1987.

Sean Goodwin, now the Kennebec County Emergency Management Agency director, was a full-time firefighter in Augusta 30 years ago, and a part-time firefighter in Hallowell.

People knew the river would rise, he said, but there was less of a warning.

“The old-timers scoffed, and the new people thought, ‘If it doesn’t affect me, who cares?'” Goodwin said.

In the three decades since the flood, technology improvements have brought Doppler radar, vastly improved satellite imagery and supercomputing systems to run forecasting models with a high and ever increasing degree of resolution.

“We would not be caught flat-footed,” Hawley said.

From his office in Hill House, the Kennebec County government building, Goodwin concurred. Because neither the Internet nor cellphones were in common use then, word went out by fax.

Now, even if the internet and the cellphone network failed, Goodwin would put his faith in another form of communication. “We could turn off all the public safety radios tomorrow and have a completely redundant system in the county with the ham radios,” he said.

Communication between agencies has improved vastly, and so has data collection and the understanding of what that data means.

But perhaps most importantly, he said, when forecasts call for more than 3 inches of rain, people now know to take note and start preparing.

No one will miss the next one, and no one doubts there will be another flood.

“It’s just a matter of when,” Hawley said.

Jessica Lowell — 621-5632

Twitter: @JLowellKJ

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.