When Inky the octopus escaped from his tank at New Zealand’s National Aquarium in April 2016, he squirmed through a six-inch-wide drainpipe and stole away into the Pacific. He stole more than a few human hearts along the way, too. Inky fans celebrated the animal who outwitted the aquarium: “Please watch out – he is heavily armed,” one commentator quipped.

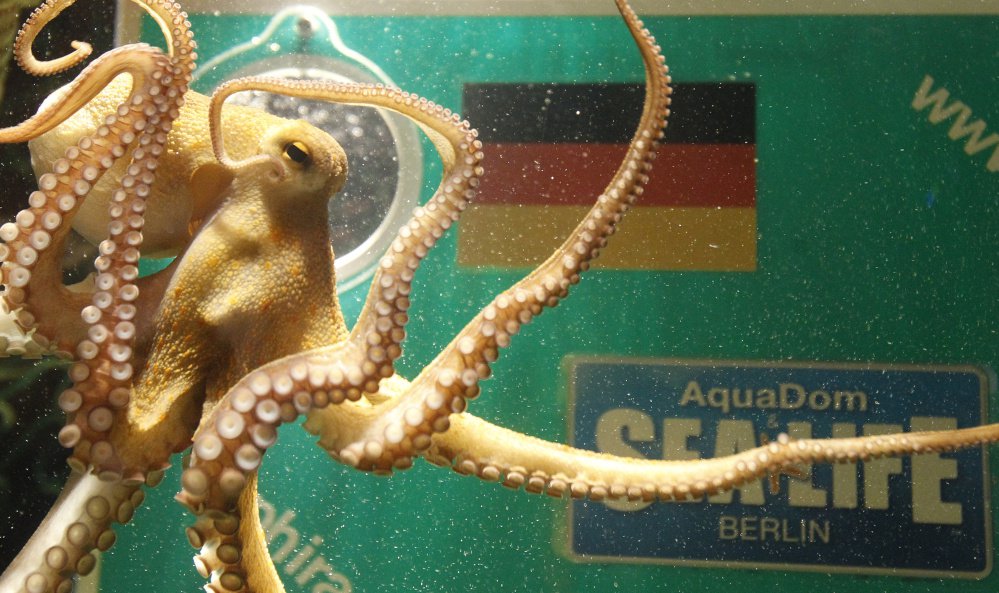

The intelligence of octopuses goes far beyond escape artistry. They can unscrew glass jars from the inside and solve other complex mechanical problems. They play. Some are capable of body-contorting mimicry. All of this is to say that cephalopods – the spineless, many-legged creatures including octopuses and cuttlefish – stand out among their fellow mollusks. Pity in comparison the oyster, a mollusk that, sadly, doesn’t even have a proper brain.

Cephalopods are unusual not only because they solve puzzles and clams cannot. Squids, cuttlefish and octopuses do not follow the normal rules of genetic information, according to research published Thursday in the journal Cell. Their RNA is extensively rewritten, particularly the codes for proteins found in the animals’ neurons.

Put simply, that’s very weird. According to the central dogma of molecular biology, cells convert DNA sequences to RNA, which then creates proteins.

Imagine a library full of cookbooks, where you’re not allowed to check anything out. But you are allowed to copy recipes as you need them. The copies must almost always be verbatim, as though done by a faithful scribe. RNA plays the role of scribe.

Very rarely, cells edit RNA, plucking out the molecule adenosine and inserting a molecule called inosine. University of Utah biochemist Brenda Bass discovered RNA editing three decades ago. “Everything we have learned in the 30 years since these were discovered says that these type of editing events usually don’t change codons,” Bass told The Post, meaning that the edits to RNA did not change what proteins are created.

“The general view was that editing sites are being ‘expelled’ from the coding part of the RNA molecules,” Eli Eisenberg, a co-author of the new study and an expert in RNA editing at Tel Aviv University, wrote in an email to The Washington Post.

But, far from expelling the edited sites, cephalopods use the tweaked RNA to generate new proteins. Rather than one gene producing one protein, this type of RNA editing, called recoding, could allow a single octopus gene to produce many different types of proteins from the same DNA.

“Recoding by editing effectively creates a new protein sequence, and thus it’s expanding the protein repertoire at the organism’s disposal,” Eisenberg said.

Joshua Rosenthal, a neurobiologist at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, and an author of the new study. says these RNA changes can have a dramatic impact on squid or octopus biology. In a study, Rosenthal discovered that octopuses living in the Antarctic used RNA editing to keep their nerves firing in frigid waters.

In the new report, scientists measured rates of RNA recoding in several cephalopod species. They found that squids, cuttlefish and octopuses – the smartest kinds of cephalopods – frequently edit RNA, in about one out of every two transcribed genes.

Could “massive RNA-level recoding,” as the scientists wrote in their new study, be related to the animals’ smarts?

The study did not provide conclusive evidence that RNA recoding was the reason for cephalopod smarts. But it offered “tantalizing hints toward the hypothesis that extensive recoding might have contributed to the exceptional intelligence,” Eisenberg said, of the squids, octopuses and cuttlefish.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.