WATERVILLE — Ben Muniz thought his baseball career was over. He starred for two state championship-winning teams at Maranacook, gone on to play at St. Joseph’s College, and that was it. He was, as he described it, “5-foot-11, 180 pounds and with two bad shoulders.” Professional life awaited him, of course, but not more baseball.

That was until he found out about the Pine Tree Men’s Baseball League, a wood bat league based in the area surrounding the Central Maine area. Now Muniz is part of the Central Maine Green Wave, playing with and against older and younger players who, like himself, are just happy there’s an opportunity to keep playing the sport they love.

“It’s a chance to be a kid again,” said Muniz, now 33. “As we get older, we have more responsibilities. Mortgage, family, all that stuff, and we make so many decisions for other people.

“This is for us. We get to go out there, and I call it ‘baseball therapy.’ No matter what’s going on in your life, we’ve always got this to fall back on.”

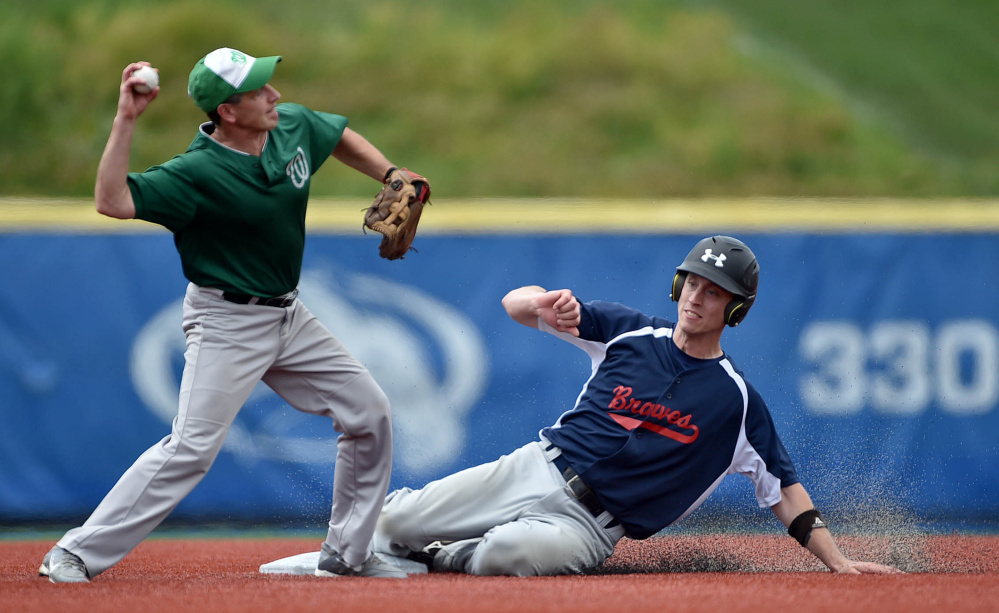

The league, which met Saturday at Colby College for its annual midseason round robin tournament, is a 10-team organization that runs from late May to early August, with roots that stretch back past the 1960s and a feel that’s reminiscent of those years, when towns had their own baseball teams made up of adults in the twilights of their playing days. Players range from 18-year-olds to men over the age of 60, from high schoolers to former major leaguers, all of whom just relish an opportunity to either resume, or resurrect, their careers on the diamond.

“It brings a love of the game for everybody,” said Kris Targett, 39, the league’s president and a teammate of Muniz’ on Central Maine. “We’ve still got the passion for it, we still love going out and playing. And that’s something that kind of satisfies that craving for us all.”

It isn’t a league of hacks. Talented players past and present dot the rosters of each of the teams, and most players were, at the very least, high-caliber players in high school. Augusta’s Rex Turner, listed in the top five for career home runs at the University of Maine, is on the Winthrop Red Sox, as is nephew Tavis Hasenfus, a former Winkin Award winner at Winthrop who eventually played for the Black Bears. Kyle Kennison, the all-time strikeout leader at the University of Southern Maine, is on the West Paris Westies. Waterville’s J.T. Whitten played at Husson College and now plays for Winthrop. West Paris’ Mike McBride played for the now-defunct Bangor Blue Ox.

Those aren’t even the most high-profile players. Matt Kinney, who played five years in the major leagues, plays for Central Maine, and Devern Hansack, who won the World Series with the Boston Red Sox in 2007, plays for the Farmington Hounds.

“You get some guys who were former D-I players, and there are even some former professional players, so you have some really good players on the team,” Hasenfus, 29, said. “And then you have a lot of guys who played in high school. So it’s pretty good. … It’s just all people that love the game.”

That includes — and is perhaps defined by — the players whose ages suggest they shouldn’t be finding ways to play competitive baseball once a week. Vassalboro’s Ken Walsh played semipro ball in the Stan Musial and Tri-State Leagues in New York before a knee injury forced him to stop at 29. At 55, however, Walsh heard of the league from Targett and couldn’t resist the temptation to go to a practice at Winslow High School and see if he could still play.

“It was like riding a bike again,” said Walsh, now 56. “The swing was there, and I was able to play the infield decent enough. The legs are not as quick as they used to be, of course.”

Walsh isn’t alone. In each game, men with gray hair and crow’s feet play alongside recent college grads who still have their fastballs and fit bodies from their playing days.

“We get guys in their 50s and 60s just looking to play another game, and we get guys right out of college throwing 90 miles an hour,” Muniz said. “It’s a really unique mixture of talent, and that’s one of the draws of this league. You never know what you’re going to see out there.”

The old-timers play with the youngsters, and more often than not, they keep up with them. It’s not rare to see a crisp 5-4-3 double play, or see a strong throw from the outfield cut down a runner trying to score from second on a single.

“It’s kind of funny. You watch these younger players come into the league from high school and college, and they’ve got the tools. They’ve got the physical tools, but they don’t have the mental tools,” Targett said. “Some of the hardest people to strike out in the league are the 40-, 50-, 60-year-old guys because they know to just put the bat on the ball. They slap it, they put it into play.”

“I’ve found that the older generation, they’re the ones more likely to run out that ground ball and get fired up,” Muniz said. “It’s a lot of fun all around.”

And it can get competitive. Most of the league’s participants, regardless of age, were serious players, and that fire — temporarily on hold for the good-natured tournament at Colby — can be difficult to put out.

“During the regular season, we have fun, we joke,” Targett said. “We have good camaraderie between the teams. But come playoff time, these guys get serious.”

The competitiveness is only part of the appeal, however. The opportunity to hang onto a game that was once a big part of each player’s life is the factor that trumps them all.

“I think the best part about it is it’s the same game you always played,” Hasenfus said. “Here, it’s the same game that you’ve always played growing up, so nothing really changes. … You get slower, your arm gets weaker, but the game doesn’t change.”

“The stuff in the dugouts, being part of a team, being a teammate, that’s kind of a nice break from the normal sort of 9-to-5 work life and the crazy things you get running around, being a parent, doing a job,” Turner said. “It’s a way to get back to your childhood for a little bit and reconnect with that element of life.”

And for some, it can be an opportunity to extend that passion for the game to another generation.

“Now my son, who’s 10 years old, he’s watching Dad at 56 playing ball,” Walsh said. “He’s watching Dad on the field, and now he wants to play ball. … I never thought in a million years he would even see that opportunity. “

Drew Bonifant — 621-5638

dbonifant@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @dbonifantMTM

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.