One of the many North Vietnamese voices in Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s film history of the war in Vietnam speaks a hard truth. For all the talk of triumph and liberation after the fall of Saigon in 1975, the speaker says, the war had visited only death, misery and destruction on his country.

In a poor, ravaged land, this was the voice of victory.

Americans have long seen the Vietnam War as their own national tragedy, which it certainly was. “The Vietnam War,” whose 10 episodes begin on PBS at 8 p.m. Sunday, exposes how the war and the official lies behind it wrenched the United States into angry factions and reddened a distant landscape with the blood of young Americans. But if it gets the audience it should, it will also broaden public understanding of the human disaster that U.S. policy inflicted on the Vietnamese, north and south.

Calculating the Vietnamese death toll has long been a challenge, but most estimates reach into seven figures. The filmmakers put the number at 3 million. One virtue of the documentary is that on this question and others it introduces viewers to individual victims and their loved ones. This puts human faces on cold statistics.

Civilians huddle together after an attack by South Vietnamese forces at Dong Xoai in June 1965. Photo by Horst Faas/Courtesy of AP

The film is Burns and his team at their best. To attract viewers, his “The Civil War” employed sonorous voices speaking as the war’s main players and creative pans of photographs, a technique now known as the Burns effect. “The War,” his World War II film, followed people from four American cities to help focus a vast global story. “The Vietnam War” is different. It neither rises slowly from the mists of time nor needs a reductive frame for its sprawling narrative.

It is a straight-up, straight-on account of the combat, carnage, anger and excesses of the war years. Its purpose is not to settle longstanding controversies but to present the evidence and allow viewers to sift it for themselves. As Burns said in a recent interview, “We wanted to be umpires, calling balls and strikes.”

That said, in many cases, the evidence is powerful.

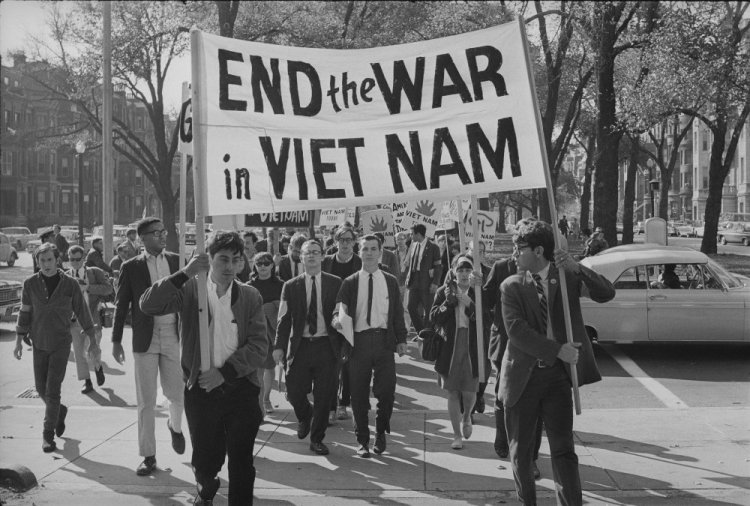

The documentary tells the political story, showing how a succession of U.S. presidents blundered into the war, escalated it and then could neither win nor escape it. While devastating Vietnam, the war fractured the United States, severing generation from generation and provoking bitter protest and lethal violence.

The war was never quite what the war presidents thought it was. They saw it through a Cold War prism, planting the American flag in Vietnam in the hope of checking the so-called domino theory. This idea, articulated by President Eisenhower in 1954, held that in the global ideological struggle after World War II, one country’s fall to communism would lead to another’s.

Ho Chi Minh, the leader of the North Vietnamese, was indeed a communist, but he was a nationalist, too. His driving ambition, pursued through decades of setbacks, was to throw off the yoke of colonialism and unite his country under self-rule. The film presents a balanced and revealing portrait of him.

American Marines on the march in Danang in March 1965. Photo courtesy of Associated Press

It also shows the lessons that might have been learned from the war the French fought to recapture their colony after World War II. U.S. policymakers had every reason to pay more attention to these lessons than they did. By the time the Vietnamese drove the French out at the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the United States was footing 80 percent of France’s military bill for the conflict.

Anyone with even a passing knowledge of the U.S. war in Vietnam will recognize its essential elements in the French failure: the futility of attempts to “pacify” villages, the night-fighting prowess of the nationalists, the demoralization of French soldiers, outrage back home over the use of napalm, even the shunning of returning French veterans of a “dirty war.” Americans would endure all the humiliations visited on the French and more.

To tell that story, Burns and Novick turned their cameras on people who lived the war. They also used archival footage – the wounded POW John McCain being interviewed, Jane Fonda in Hanoi. Their researchers found little-known clips from audiotapes that allow viewers to eavesdrop on the cynicism and hypocrisy – and worse – of presidents. But their focus through all 10 episodes is on the remarkable testimony of warriors, civilians, protesters, disillusioned veterans, the families of the dead.

Ken Burns sand Lynn Novick, co-directors of “The Vietnam War” Photo by Stephanie Berger

Viewers will catch a glimpse of some of these witnesses in the first episode. Speaking of the protests back home, one of them, Ron Ferrizzi, says, “I saw somebody who looked like my dad hitting somebody who looked like me. Oh, my God, whose side would I be on?” Like other such quotations, these words from a one-time helicopter pilot in Vietnam foreshadow the heart of the story.

The narrative power of the film rides on the journeys made by characters who return episode after episode. The girl whose brother died early in the war struggles for years to understand and accept the loss, only to have her grief transformed at the Vietnam Wall. The veteran and author Tim O’Brien dissects “the failure of conscience” that kept him from defecting. A veteran of cave warfare says after killing a man for the first time, “The other casualty was the civilized version of me.”

In the context of the painful truths uttered by these witnesses, the decisions, lies and evasions of American leaders sound even more contemptible than they did when the country first heard about them. They begin with the “body count” approach to measuring the war’s success, a policy that sanctioned indiscriminate killing. Then there is Lyndon Johnson saying in private in 1965 that “there ain’t no daylight in Vietnam, not a bit.” There is George Ball of the State Department warning Johnson, as he did President Kennedy before him, that the war can’t be won. There is the stream of public weasel words: “We’re better off than we thought we would be at this time.” “There is light at the end of the tunnel.” “We have reached an important point where the end begins to come into view.”

And then there is Richard Nixon, who, days before the 1968 election, scuttled LBJ’s efforts to initiate peace talks. Long denied by Nixon, the plot hinged on convincing President Nguyen Van Thieu of South Vietnam to block the peace initiative until after the election. Evidence discovered last year finally confirmed Nixon’s role. The Burns documentary tells the story in the context of its time.

In exchange for his cooperation, Thieu experienced the other side of Nixon in 1971 when the president told another lie. The way out to bring American troops home was to turn the fighting over to Thieu’s Army of the Republic of Vietnam. When Nixon assured the public that “Vietnamization is working,” he knew it wasn’t. “This little speech was a work of art,” he told Kissinger afterward. “No actor in Hollywood could have done that.”

From there, the war descended into American abandonment, fratricidal conflict and a Communist victory that led to 10 years of hunger, brutality and murder. Nixon resigned in disgrace nine months before the last helicopter left the roof of the U.S. embassy in Saigon. President Thieu went into exile and lived out his life in Foxborough, Massachusetts. The war veterans tried – struggled, many of them – to regain their equilibrium.

In a time when the internet has shortened attention spans, it is doubtful that an 18-hour documentary history of the Vietnam War will mesmerize the country as Burns’s “The Civil War” did in 1990. But “The Vietnam War” deserves an ample audience.

Unlike Burns’s other war films, it is not a story of human savagery redeemed by good triumphing over evil. The Vietnam War doesn’t end slavery or vanquish fascism. Possibly that is why so many Americans of the 1960s and ’70s averted their gaze years before it had played out. But Burns, Novick and their crew have transformed it into a gripping human story from beginning to end. Viewers will find no truer, fuller, more masterful telling of the war that requires so little time or effort on their part.

Mike Pride is editor emeritus of the Concord (N.H.) Monitor and retired administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.