Fred Beckey, an American alpinist who helped establish the sport of modern rock climbing and who developed a dual reputation as an irascible “dirtbag” mountaineer and unmatched chronicler of North American peaks, died Oct. 30 at a friend’s home in Seattle. He was 94.

The cause was congestive heart failure, said Megan Bond, his friend and biographer.

Although little-known outside of climbing circles, Beckey was considered the finest mountaineer of his generation and one of the most prolific alpinists in history, recording hundreds of first ascents across the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest and in mountains as far afield as China and Tanzania.

“People talk about young climbers today and how prolific a person might be. But there’s just no comparison with Fred,” Phil Powers, executive director of the American Alpine Club, told Outside magazine in 2010. “I mean, it’s not one level, but 10 levels of magnitude more than the second-place guy. If you travel the American West, open any guidebook, try to do any route, try to do any mountain, you’ll likely come across Fred’s name.”

Beckey possessed a gecko-like talent for scaling vertical rock walls and a wanderlust that scarcely dimmed over eight decades of alpine exploration. Born in Germany, he settled in Seattle as a boy, learned to climb while in the Boy Scouts and scaled the 5,700-foot Boulder Peak in the Olympic Mountains by himself at age 13.

In part, climbing offered Beckey an escape from the schoolyard taunts that led him to change his given name, Wolfgang, to Fred. There were also more elemental concerns: “a longing to escape from the artificial civilized order, a need for self-rejuvenation, a desire to restore my sense of proportion,” he once said.

Beckey never married, never had children and never kept a full-time job that would prevent him from striking out on a whim for the Gunks of New York or the Bugaboos of British Columbia. By all accounts, the sole rival for his interest and affection was women. His only major fall, friends said, was one he took off a bar stool at the sight of a lady.

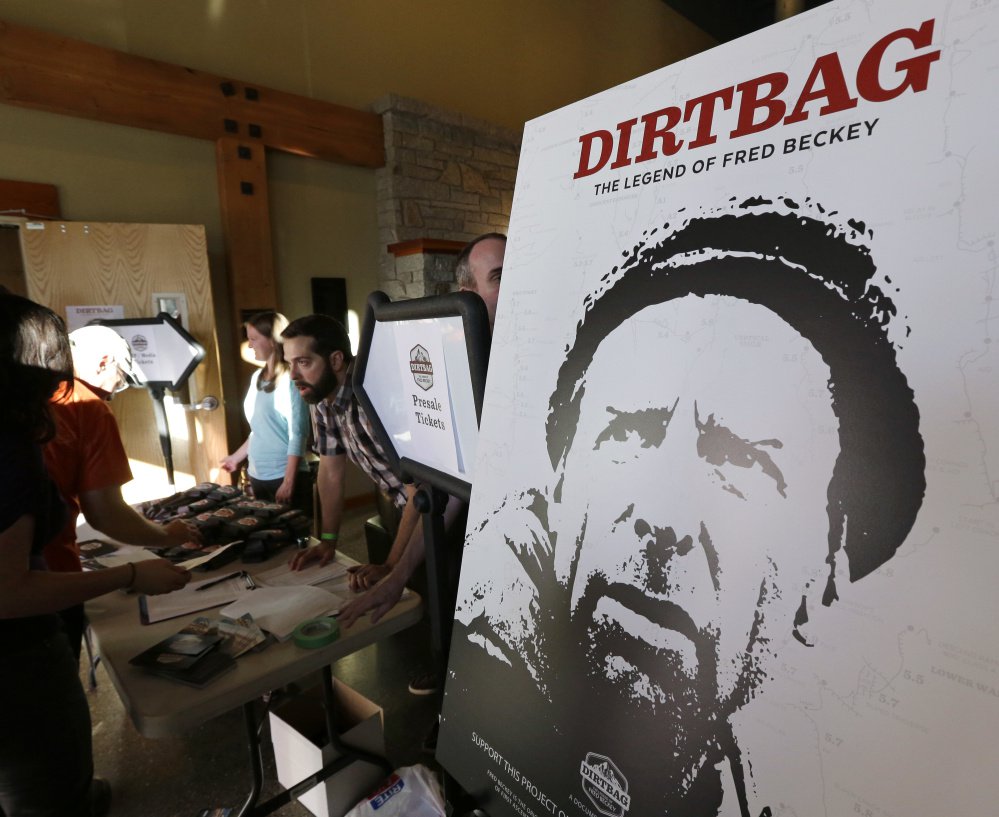

In climbing parlance, Beckey was the ultimate mountain-minded nomad, or “dirtbag,” a term used as the title of a 2017 documentary about his life. He used a weathered McDonald’s coffee cup to receive free refills on the road, and maintained a makeshift Rolodex in the trunk of his station wagon, a collection of cardboard scraps that listed potential climbing partners – some of them one-third his age – whose couches he could crash on in his travels.

Gleefully embracing his dirtbag image, he staged a photograph, later used as a Patagonia advertisement, in which he appeared as a disheveled hitchhiker on the side of the road, decked out in climbing gear and carrying a cardboard sign that read, “Will Belay For Food!!!”

Yet Beckey worked far more than most climbers knew, Bond said, spending years in the printing and marketing industries while writing a dozen books that mixed scholarship with hard-won wisdom. His three-volume “Cascade Alpine Guide,” first published in 1973, became an indispensable reference work known to climbers as the “Beckey Bible.” One of his final books, “Range of Glaciers” (2003), was a sweeping piece of scholarship that detailed the 19th-century exploration of the North Cascades. Beckey reportedly spent 15 years researching the book.

“If Thoreau and Emerson describe the transcendental American theme, then Beckey – after Ahab, akin to Kerouac – describes the oddly manic drive to scale and map and detail the wilderness in a modern way,” Steve Costie, executive director of the Mountaineers climbing club, told The New York Times in 2008. “Almost adversarial; never transcendental.”

Wolfgang Paul Gottfried Beckey was born in Zulpich, near the German city of Dusseldorf, on Jan. 14, 1923. His father was a surgeon and his mother was an opera singer.

Described by many climbers as fiery and single-minded on the mountain, Beckey spent many of his early years in tense association with the Seattle-based Mountaineers group, climbing peaks that other members said were unclimbable, including Mount Waddington.

The 13,200-foot peak in British Columbia had been ascended just once before. Beckey climbed it at 19. Climbing with his younger brother Helmut Beckey, who survives him, he sported tennis shoes that he covered in wool stockings when the terrain became slippery.

The climb established Beckey as something of a daredevil, and whether through bad luck or poor leadership, members of several of his early expeditions were severely injured or killed, including on a disastrous 1955 trip to the Himalayas.

Beckey had by then graduated from the University of Washington, receiving a bachelor’s degree of arts in economics and business in 1949, and performed what some climbers described as his “Triple Crown”: The 1954 ascent of Mount McKinley and the previously unscaled mounts Hunter and Deborah in Alaska.

The following year, however, Beckey’s reputation in American climbing cratered during an international expedition on Lhotse, an unconquered peak in the Himalayas. Forced to stop during a storm, Beckey “left a weakened climber on the mountain,” according to a 2010 account in Outside magazine, destroying his relationship with expedition leader Norman Dyhrenfurth, who died in September.

When Dyhrenfurth led the first American expedition to Mount Everest, resulting in fellow Seattle climber Jim Whittaker’s reaching the summit in 1963, Beckey was not invited. “It was a big thing,” Beckey told Outside. “But I didn’t take it too hard.”

He responded instead by notching an astonishing 26 first ascents in 1963, climbing more than 40 peaks in all.

Beckey was planning to return to the Himalayas before he died, Bond said, although not to climb. His strength had finally dissipated, and he was to be carried by porters into the mountains of Garhwal, in India.

“You’re putting yourself on the line,” he told the Times, describing the appeal that climbing maintained for him, even in old age. “Man used to put himself on the line all the time. Nowadays we’re protected by the police, fire, everything. There’s not much adventure left. Unless you look for it.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.