“Exceptional Objects,” now on view at Grant Wahlquist Gallery in Portland, features the work of two Yale-educated artists. Kate Greene is a photographer who teaches at Maine College of Art. Bill Albertini is a New York-based sculptor.

Greene’s beautifully stark photographs take the form of black-and-white studio still lifes featuring installation-like images of plants, fabric, mirrors and paper, as well as images that appear to be constellations in the night sky. While they look like negative-based black-and-white photographs, some of which have not been “spotted” (cleaned up), a closer look reveals them to be digital images. That they are “archival inkjet images,” according to the object list, indicates at least one phase of digital handling, but it doesn’t mean that a given image isn’t, say, a collodion wet plate photograph that was scanned and then printed digitally.

We’re at the point where the source and possible digital manipulation of an image is not necessarily indicated on its object label. I certainly don’t see this as a problem; it’s been a fact of art for centuries. The camera obscura came into use in the 16th century. Tracings and rubbings were around long before that. And photography has been colorized and manipulated practically since it was invented almost 200 years ago. Maybe what we’re feeling now is simply the doubt we should have always felt.

Bill Albertini, “Braced Bracket,” 2017, mahogany, Plexiglas, polylactic acid plastic, laser-cured epoxy resin, 24 by 22 by 94 inches. Photos courtesy of Grant Wahlquist Gallery

Albertini’s sculptures and images approach digital phantasmagoria from the opposite path. Instead of beginning as objects, they are birthed (at least in terms of their key parts) as digital designs. His “Braced Bracket,” for example, is listed as a 94-inch work in “mahogany, Plexiglas, PLA plastic and laser-cured epoxy.” We see it as an 8-foot, 2-by-4-shaped mahogany board that nestles through a square, clear plastic window of Plexi. But the wood does not continue through the window. It is two lengths of mahogany joined by about a foot of 3D-printed armature.

A handsome grid of 25 framed digital renderings of hardware pairs reveals the story of Albertini’s process. He designs the hardware for his sculptures using 3D rendering software and then 3D prints them in polylactic acid (PLA) plastic. This is the new world of object art. To the quick glance, the gridded images could be photographs of his hardware objects, chromed in their metallic solidity. But they are (merely) digital renderings. The irony now is that such paperless designs can be made into real objects with a 3D printer.

Plato, I imagine, would be pleased.

As objects, however, they appear with a stunning sense of organic presence. The default color of Albertini’s PLA is like beeswax – the ultimate mathematical organic building material.

Bill Albertini, “Prop & Corner Brackets,” 2018, mahogany, polylactic acid plastic, laser-cured epoxy resin, 52 by 45 by 47 inches.

Albertini’s two other sculptures play more to the notion of the organic. Both actually look to the symmetry of the human body which, in turn, more easily relates them to the sculptural work of Joel Shapiro, one of America’s greatest sculptors, and an artist who managed to bridge minimalism with the symmetrical pulse of the human form. Albertini seems to channel both Shapiro’s figurative abstractions and Richard Serra’s work, made by forcing molten lead into the corner of a room with slick (however Frankensteinian) updates on their connective bolts. “Angle Bracket” connects two pieces of mahogany. This time, it acts asymmetrical, yet is a left and a right side held in place by three elements of hardware at the ends and in the middle. “Prop & Corner Brackets” looks like a combo of Shapiro and Brunswick sculptor Duane Paluska, but, again, it seeks to camouflage its conceptual symmetry. The gesture is like that of a dancing, bending body, but while its legibility as a subject might be hidden, its grace and human appeal is not.

While Albertini’s hardware studies appear as product photography – a place we expect the slick and perfectly presented – Greene’s unlikely objects appear in the traditional visual language of art: still life. Her camouflage consists of hiding in the open. Her “Scindapus pictus,” for example, features a sinewy tangle of the invasive silver vine hovering in a high focus over a studio light-feigned trapezoid. While clearly a still life, the structure of the image looks heavily to abstraction. “Studio Study No. 6” exudes the same formal presence, but with enough subtle marks that we begin to see them as large-format photography flaws: negative scratches and so on. With its center filled by a square of black velvet (with clear references to painters like Ad Reinhardt or Kasimir Malevich), “Studio Study No. 2 (black velvet, smoke)” is an even more direct reference to Modernist painting. The image is filled at the lower left with smoke-like (but fake) lens-flaring and marked with fake lens scratches, so that it feels like a period image. Still, it is somehow troubled by these theatrical invasions, but only after a longer look, and by then it’s clear Greene is going far deeper than pretending to make a painting.

Kate Greene, “Studio Study No. 6,” 2018, mirrors, plastic, paint, 14 by 11 inches.

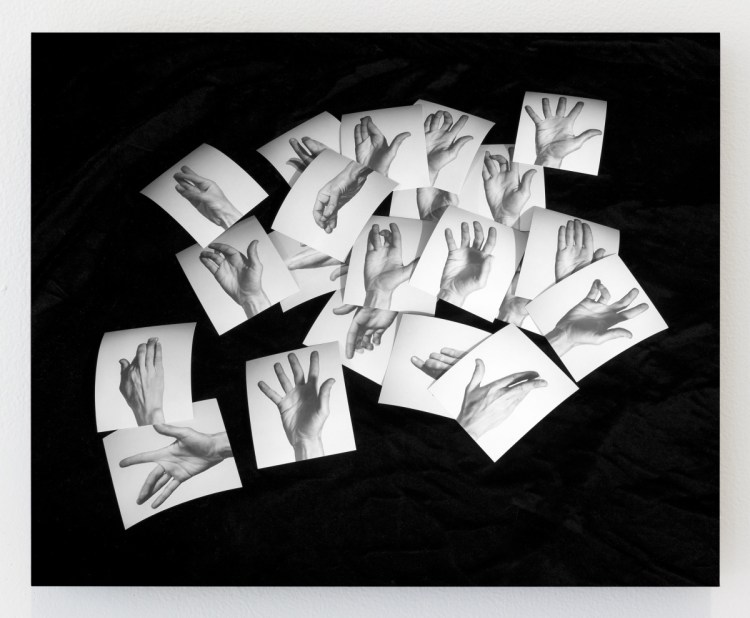

Greene’s range at first appears almost arbitrary. Her images include a set of pictures of hands and scenes of the starry night sky. But these come together as well on theatrical terms. The color of telescopic imagery is added later to help clarify differences in qualities of light. And Greene’s images are actually fireworks simply pretending to be telescopic pictures. The hand images in “Yvonne” directly reference the hand images from minimalist choreographer and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer’s 1966 “Hand Movie.”

The title “Exceptional Objects” might first appear as a merely aggrandizing shout of support for the work in the show, but it opens the conceptual basis of the show. An exception, after all, isn’t necessarily a good thing; it’s just something that falls outside of the norm, our expectations, the rules. To kick this consideration into play, Wahlquist quotes the journalist Ambrose Bierce, author of the “Devil’s Dictionary,” in which the writer correctly notes that the Latin phrase “Exceptio probat regulam” means that “the exception tests the rule, puts it to the proof, not confirms it.” Calling for testing is an unlikely philosophical idea to pull Albertini’s and Greene’s work together, but it does. In this light, Albertini’s work is primarily based in system logic, and Greene’s pursues the relationship between theatricality and reality.

“Exceptional Objects” is a beautifully installed show chock-full of elegant ideas.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.