It is, to use a trite but wholly appropriate term, a teachable moment.

When the University of Southern Maine removed three pieces of art from a gallery at its Lewiston-Auburn campus, it raised tough questions about punishment, redemption, the First Amendment, and art itself. Just the kind of questions college students should be asked to grapple with.

The pieces of art were by Bruce Habowski of Waterville, a highly regarded painter whose works have hung in prestigious galleries.

But Habowski also spent six months in jail for a 1999 conviction for felony unlawful sexual contact, and had two other sex-related misdemeanors.

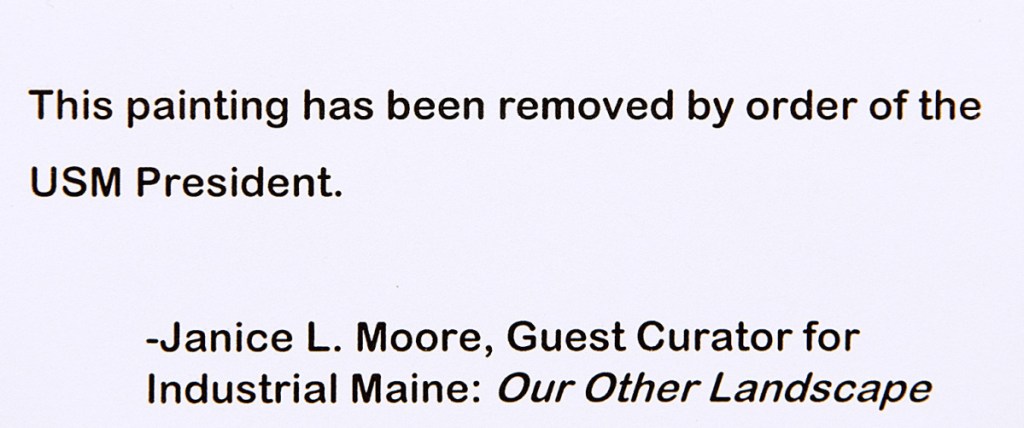

After a relative of a victim of Habowski’s called the university, USM President Glenn Cummings had the paintings removed, prompting the show’s curator to accuse him of censorship.

This is not an issue of free speech. An artist has a constitutional right to create art, but no right to show that art at the University of Southern Maine.

Likewise, the university has a clear right to display what they like, and they have a particular obligation to police that in this case, as the art is displayed in a central entryway and commons area that cannot be avoided by students going to class. That is, once the art is on the wall, students have no real choice but to see it, even if that student was a victim of the artist.

In this moment of #MeToo awareness, as well, there would be no excuse for the university to stand behind an artist convicted of criminal sexual activity. Not when there are so many artists who haven’t, and there is such a regrettable history of artists getting away with inappropriate and even criminal behavior just because of the power of their work. Not when so many college students are themselves victims of sexual trauma.

(It should be noted that Cummings has a solid record on free speech, having allowed controversial speakers at the university over the objections of student groups. The difference, the president said, is that students can decide whether or not to attend such a speech.)

But there are other questions raised by the paintings’ removal, ones similar to those being raised in the larger culture.

How much should an artist’s behavior factor in our enjoyment of their art? Is it possible to separate the two?

And when does an artist — or any other public figure — forfeit their ability to participate in the culture? Certainly the severity of the crime and the level of remorse matter. What do they have to do to be allowed back in, if they should be at all? How do we balance that with the rights of their victims, which of course are paramount?

These are challenging questions with no easy answers, and they are perfect for a generation of students coming along in a culture that seems primed to confront the hypocrises of the past. When we dismiss the transgressions of people who otherwise have attributes to admire, from the Founding Fathers to the imperfect writers and moviemakers whose work moves us, we miss precious context, and fail to move forward.

We can argue over the fate of the removed paintings, but there’s no doubt that these tough questions deserve a spot at the university.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.