Train to be a recovery coach. Consider being a foster parent to a drug-affected baby. Attend a community forum about opioid addiction and recovery. Help neighbors understand that addiction is a chronic disease and not a moral failing of the person affected.

Those are suggestions Gordon Smith, director of opioid response for Gov. Janet Mills’ office, offers to people who want to help stem the opioid epidemic in Maine.

“The most important thing is stigma,” Smith said Friday, “and there’s something that every citizen can do. Janet wants to put the message out there that there is hope for people, and we all need to use nonstigmatizing language.”

Smith was appointed by Mills last month to work with a new prevention and recovery cabinet, whose members will be from all state departments, including Health and Human Services, Public Safety, Corrections and Education. The cabinet will ensure coordination and communication across state agencies in combating the opioid crisis through law enforcement, prevention, treatment and recovery. The group expects to meet for the first time within the next couple of weeks.

Meanwhile, Smith has been talking to groups around Maine about the work being done and asking what communities need from the state to further their work on the opioid problem.

At 6:30 p.m. Feb. 28, Smith will be among the speakers at a community forum to be held in the Chace Community Forum room at Bill & Joan Alfond Main Street Commons, at 150 Main St. in downtown Waterville. Other scheduled speakers are Waterville police Chief Joseph Massey, whose department runs a HOPE program for those seeking treatment; Colby College Professor Winifred Tate; and Lisa Hallee, who lost a family member to the opioid crisis.

“It’s been a joy to speak on behalf of the governor to say, ‘I’m here for anyone who needs it,'” Smith said. “‘How can we help you be more successful in what you’re doing and how can we help you have a larger impact?'”

CONFRONTING THE OPIOID PROBLEM

“It’s complicated,” Smith said. “Everybody’s journey and recovery is different. Housing is important and transportation. We need counselors, recovery coaches. You need a whole army of support for that person.”

Smith, former executive vice president of the Maine Medical Association, has been working to make more of the overdose-reversing drug naloxone, or Narcan, available, increase reimbursement for treatment and lessen requirements for physicians prescribing medication. He is working on housing issues. There are 101 “recovery residences” in Maine, for instance, but only 18 will take a patient who is on Suboxone, a medication used to treat opioid addition. Transportation is important for patients in rural areas.

Mills’ executive order lists 23 steps to take in combating the opioid epidemic including the purchase of 35,000 doses of naloxone to be dispersed around the state; integrating medication-assisted treatment into the criminal justice system, including in jails and prisons; and creating a statewide network of 250 recovery coaches, including 10 full-time coaches assigned to hospital emergency rooms, who will help people as they navigate their struggles with substance use disorder.

While the needs are great, Smith points out that the Augusta and Waterville areas are fortunate because resources can be found at MaineGeneral Health, Kennebec Behavioral Health, HealthReach, Discovery House and other providers.

“We’ve had a robust program at MaineGeneral for a long time and it’s continuing to grow,” he said. “MaineGeneral has really done a terrific job at expanding the number of Suboxone providers they have. They’ve really been a leader. They’ve got grants to do harm reduction. I can’t tell you how impressed I am with what they’re doing.”

MaineGeneral has an emergency room program that offers Suboxone, coaching and other treatment and is one of four or five hospitals in the state to do so, Smith said. The goal is to have all 33 emergency rooms in the state offer such a program, he said.

Steve Diaz, chief medical officer for MaineGeneral Health, says that with Mills’ and Smith’s efforts, he believes there will be more opportunity to stabilize people with opioid addiction or dependency who come into the emergency room, to get them the right medicine and help them get into a treatment program.

“There’s no one thing here that helps everybody,” Diaz said. “Some people need more counseling than others.”

Opioid addiction or dependency treatment can typically be done on an outpatient basis, Diaz said. The current focus nationally is on Suboxone for treatment, but it is not the only medication available. Methadone also is used, though some patients, such as those with potential heart problems, have reasons not to use methadone.

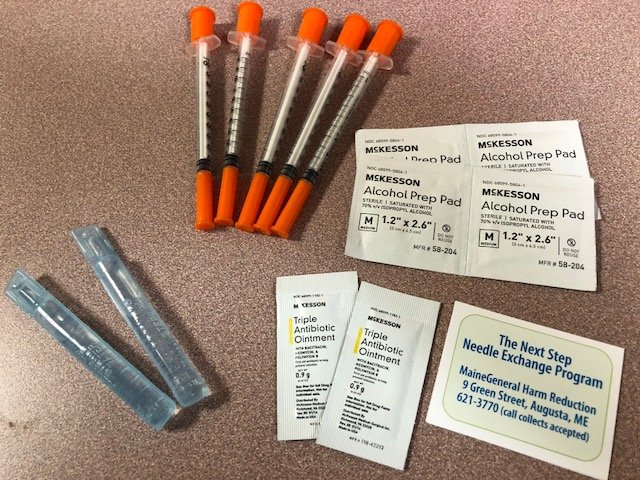

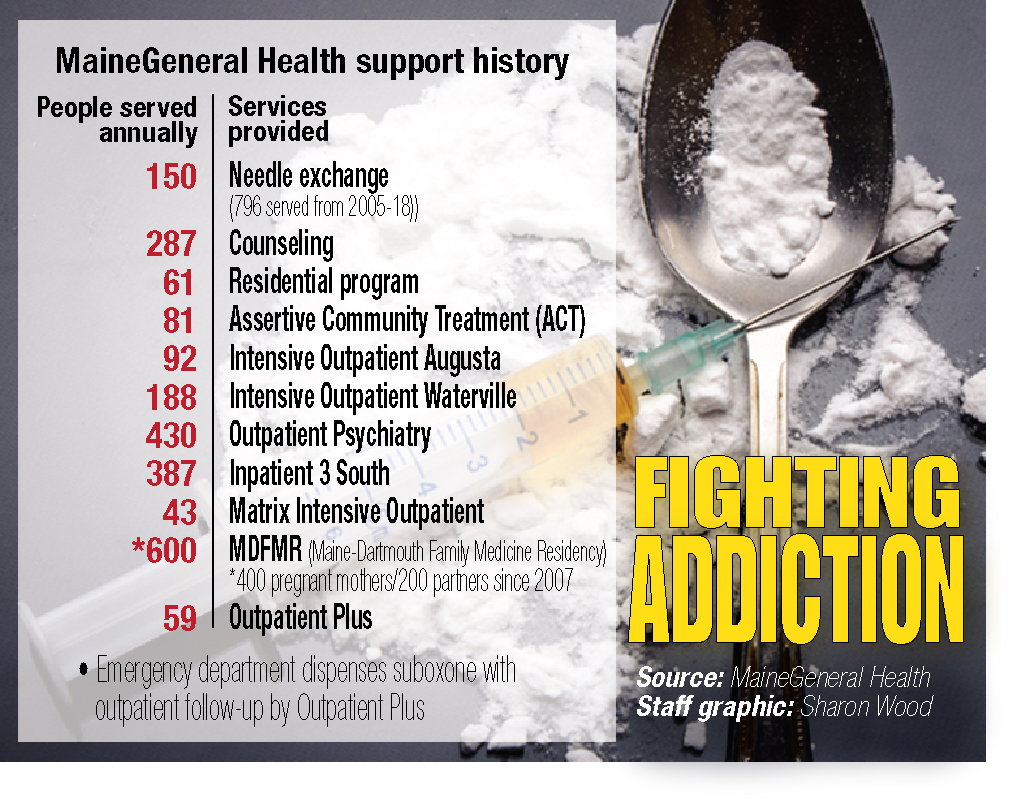

Only six needle exchange programs operate in Maine, and MaineGeneral has two at its Waterville and Augusta campuses. The hospital’s program has served 796 people from 2005 to 2018. MaineGeneral also offers counseling, a residential program, intensive outpatient services in both cities, outpatient psychiatry, a program at Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency that serves pregnant mothers, and an inpatient program in Augusta that serves 387 people a year.

People wanting to get treatment have options. They may go online to get numbers, call MaineGeneral or another provider or contact their primary care physician. A person who has no resources readily available should go to an emergency room, Smith said.

FUNDING TO ADDRESS CRISIS

Combatting the opioid epidemic costs money. Smith said $1.6 million is available in the Office of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services.

Of the $1.6 million, $600,000 is targeted to buy naloxone, $500,000 is earmarked for recovery coaches in emergency rooms and $500,000 is designated for training 250 or more recovery coaches.

“That’s just a down payment,” Smith said, adding that grants, federal money and private philanthropy are also available.

The governor asked Smith and others to find out what money the LePage administration did not spend or what was not applied for. “We found quite a bit,” Smith said, though he would not divulge how much.

Mills took a big step in helping people get services by expanding MaineCare, Smith said. It is more difficult to get people into recovery who are not insured.

“Every day, more people are qualifying,” Smith said, adding 70,000 to 80,000 will qualify for MaineCare, 10 to 15 percent of whom need treatment for substance use disorder. “This will help that gap.”

Smith said the state does not certify or license recovery houses, but it can provide incentives for them to pursue national certification. Currently, a person with low income who has a mental health diagnosis is entitled to a housing voucher; but a person who has only a substance use disorder is not eligible.

ORIGINS OF THE PROBLEM

Smith recalled the epidemic started around 1995 and culminated in 2000-2015. In 2002, he gave his first talk with a drug enforcement agent in Presque Isle about Oxycontin infiltrating Aroostook and Washington counties.

In the mid-1990s, pharmaceutical companies told the medical community that opioids, particularly Oxycontin, were safe for chronic pain, he said. “They said it was not addictive, and of course, it was very, very addictive.”

People who took opioids for pain then turned to heroin and then heroin became laced with fentanyl.

“There were 72,000 fatal overdoses in this country last year, and 46,000 were opioid-related,” Smith said. “We only lost 58,000 in the whole Vietnam War.”

At least 1,630 people in Maine died from overdoses in the last five years, he said. In 2017, 418 people in Maine died from drug overdoses, representing more than one a day. In 2017, 908 children born in Maine were affected by drugs.

Though the use of opioids will show a decrease when the numbers are tallied for the year, an increase in cocaine and methamphetamine use is occurring, he said.

“That is why prevention is so important. We have to have more people out there saying, ‘Why are there so many people in Maine abusing substances, opioids, alcohol?”

Trauma, adverse childhood events, poverty and other issues play into the equation, Smith said, and that is why a comprehensive approach is important.

“If we don’t fix the opioid problem, then it’s almost impossible for the state to be the kind of place we want it to be,” he said.

COMMUNICATION AND COORDINATION

No one has a master list of all the things happening around the state to combat the opioid epidemic, and that is one of the things the state is working on.

Both Smith and Diaz say education is an important part of the process and it should start with children — and their parents — when the children are young.

“We’re going to put a lot of prevention effort into the Department of Education to look at curriculum,” Smith said. “The health curriculum frequently is not mandated until high school.

“It’s shocking, but if you start teaching kids in high school, forget it. It’s way too late,” he said.

Diaz agrees. The opioid epidemic is worse now than five years ago, he said, though more is being done now than five years ago, but Maine has not turned a corner yet. It is important, Diaz said, for schools to educate children and for parents to become role models so children will not want to try substances in the first place.

“We need to go upstream,” Diaz said. “We need to get in front of kids from 9, 10 years old. This is a long-term problem. This will take a generation to get in front of.”

Community-based policing also is key, according to Smith.

A full-time social worker for the Portland Police Department, for example, responds to every overdose incident, goes into the emergency room or to the patient’s home if he or she does not want to go to the hospital, and helps the person through the process, Smith said.

“That’s how you’re going to save lives. When you really let people know when they’re ready for treatment, call this number and we’ll get you into treatment.”

Smith recalled being asked recently what the difference is between the Mills administration’s efforts and those of the LePage administration. He answered: “It’s the difference between day and night. This governor is reaching out to people who are actively using and saying, ‘We want to help you.'”

“There are so many things we haven’t done in Maine that other states are doing and we can borrow from them,” he said.

For instance, other states have emphasized the treatment of those in prison, Smith said. Randall Liberty, commissioner of the Department of Corrections, recently visited a prison in Rhode Island, a state that has been successful with its treatment programs.

AGENCIES SEE HOPE IN NEW PLANS

Carla Stockdale, clinical director for Kennebec Behavioral Health, and Pat McKenzie, administrator of outpatient and substance use disorder services for the agency, say Mills’ efforts to combat the issue provides a sense of hope.

Mills, they said, has done two critical things to expand access to treatment and prevention — opened an avenue to help fund health care costs and made naloxone more available.

“If we saved one person a day, that would be 50 percent of the death rate in Maine,” McKenzie said. “Not enough can be said about the governor’s approach.”

Kennebec Behavioral Health has offices in Waterville, Augusta, Skowhegan, Winthrop and Farmington that partner with primary care physicians who prescribe Suboxone and KBH provides addiction care.

The governor and Smith advocate for the development of models that support agencies such as KBH that look at the whole person being treated, according to McKenzie and Stockdale.

They said KBH is working closely with Redington-Fairview General Hospital in Skowhegan to explore the needs of the community and make plans to develop more addiction care and treatment, and that is the sort of thing the governor supports. Redington-Fairview has taken a “forward and assertive approach” to meeting the needs of the community and advocating to meet those needs, McKenzie and Stockdale said.

“Being able to get on the front line and stop an overdose — we have to do that simultaneously with increased treatment and prevention,” McKenzie said. “We can’t be either-or any longer.”

She and Stockdale said being able to address the crisis in a comprehensive way was on hold until Mills came onto the scene.

“This is an opportunity for us to really grapple with something that has affected people in Maine in many ways,” McKenzie said. “What we learn we’ll be able to apply to other substances people are struggling with.”

Amy Calder — 861-9247

acalder@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @AmyCalder17

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.