SKOWHEGAN — A town employee whose farm land is used for the storage of treated sewer sludge from the town’s water pollution control plant is not in violation of the town’s code of ethics, despite getting paid more than $10,000 annually for the service.

That comes this week from Skowhegan Town Manager Christine Almand after a resident raised the issue Tuesday night at the annual Town Meeting. The resident, who Almand said was Sarah Tracy, rents a place near the Lily Pond Farm LLC holding facility and claims the land owner Jeff Hewett, Skowhegan’s economic and community development director, has a conflict of interest in the sludge agreement, which has been in place for 20 years.

“It is not a conflict of interest,” Almand said this week. “It’s not a conflict of interest because although Jeff Hewett may be a principal of Lily Pond LLC, he was not involved in approving this agreement in any way, shape or form. He’s not approving the land lease agreement that is continuing and has been in place for decades. We are receiving something for this contract, and he is receiving a monetary gain for their part of it.”

Almand said the town’s Code of Ethics is something that was adopted by the Board of Selectmen, not by ordinance or public policy by residents at a town meeting. The board made an agreement with Hewett’s late mother, Gloria Hewett, for use of the land and buildings for an annual fee 20 years ago.

Tracy pointed out that, as the town manager, Almand “shall endeavor” to ensure that all town employees adhere to the standards of the Code of Ethics. Almand said state statutes on codes of ethics also note that even with an elected town official, such as a selectman, that person would be able to remove himself or herself from any discussion or vote and avoid any suspicion of conflict of interest.

Almand said that has been done and that there is no conflict of interest or violation of any code of ethics.

“He is no way part of the authorization process,” she said.

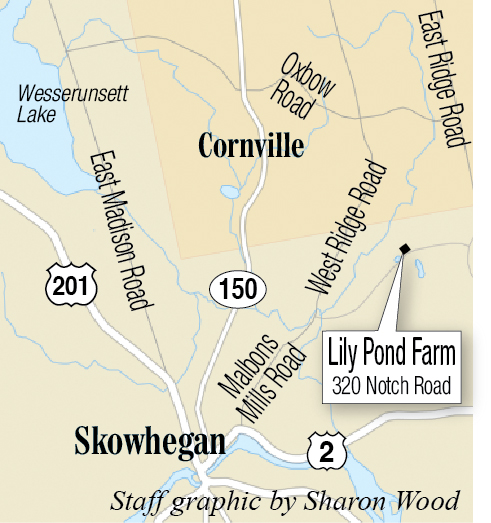

Skowhegan residents at the Town Meeting approved Tuesday a new 10-year lease agreement for the holding facility, located on Hewett property off Notch Road in Skowhegan, about 4 miles from downtown. There is a locked gate leading into the site, which is another quarter-mile off the road.

The total to be paid to the Hewett family for use of the property this year is $10,694. Payment is due in September.

Brent Dickey, the town’s pollution control supervisor, said this week that the storage building where sludge is mixed with sawdust is 130-by-60-feet in size.

The finished compost is being applied at a maximum of 5 wet tons per acre.

Dickey said all state Department of Environmental Protection permits are up to date.

In May, the Maine DEP began requiring wastewater treatment plants to test samples of treated sludge for so-called PFAS before the material could be spread on farms as fertilizer or used as compost.

The department ordered the testing in response to extremely high PFAS contamination found on an Arundel dairy farm that spread treated sludge, or biosolids, for decades as fertilizer. The farmer, Fred Stone, has said his multi-generation dairy business is ruined because PFAS are still present in his herd’s milk despite installing a costly water filter and trucking in feed from other states.

Gov. Janet Mills issued an executive order in March that created a task force to determine the scope of contamination in Maine from the chemical compound linked to cancer and other health problems.

The chemicals, known as perfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS, were used for decades in nonstick cookware, stain-resistant carpeting, food packaging and firefighting foam. While PFAS are no longer manufactured in the U.S., there is growing concern about drinking water contamination — particularly near military bases — from the long-lasting chemicals that accumulate in the body over time.

Maine has several known PFAS contamination sites, including the former Brunswick Naval Air Station and a source well for a York County water district. But there are likely other sites, given the prevalence of the chemical.

“That is why it is important for the state to identify any locations in Maine where PFAS are prevalent; examine its effects on drinking water, freshwater fish and marine organisms; and take steps to create and implement treatment and disposal options,” Mills said in a statement. “The EPA is dragging its feet on the issue, leaving states to take the lead.”

Almand said the town, as well as other towns in Maine, received a memo from the DEP in May saying that the town needs to test and get approval on use of the material as a fertilizer, which Skowhegan has done and has received approval for land use.

“This is new stuff that the state’s still trying to figure out,” she said. “Some of the information is very new, and they’re still researching. It’s more than just one compound. I’m sure we’re going to have to do a lot of testing in the future.”

Almand said $3,000 was added to the pollution control budget for the coming year for lab testing.

For his part in the discussion, Hewett said he has no role in the sludge composting or spreading on corn and hay fields.

“I have nothing to do with the operation, so I don’t have a clue. I know this is sawdust, and I know these (piles) are mixtures of the sludge, but what the process is, I don’t know anything about it,” he said. “I’m not involved in it and don’t know anything about it.”

Hewett, 61, said the mixture is “cooking” in piles in the holding facility, and air is pumped into the piles to move the process along.

There is an odor to the material, he said, but that diminishes as the piles ferment. He said it is not a regulated product once the composting process is complete and can be spread on fields.

He said the town contracts with his brother, Tim, to oversee the composting and the ultimate land use. The family owns about 500 acres on the farm. He said his father bought the property about 75 years ago.

The land is leased out for the spreading of the finished material.

Hewett said he doesn’t worry about using the mixture around the house, in flower gardens and on the lawn but would stop short of using it on a vegetable garden, just in case.

“Up to this point in time, the testing has always been good. DEP’s had no concern, but I’m not writing off the concerns that have come up,” he said. “My understanding is that most of that is in the heavy industrial (material) in the pollution control facility. I will become real concerned if we find that it’s in everybody’s septic, but up to this point in time, all the testing that’s been done, there’s no issue.”

Hewett said composting the sludge and mixing it with sawdust may be the safest way to handle the residue from the pollution control plant.

He said there is no conflict of interest for his family’s part in offering the land to the town, just a continuation of the agreement originally crafted by his mother in 1999.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.