Jeff Pidot remembers the terrible beauty of trees bowed under the weight of thick, glistening ice. He can still hear the sharp ricochet of branches splitting and cracking, like gunshots rifling through his Hallowell neighborhood.

“I will never forget the sound and the horrible sense of being in a war zone, especially at night,” said Pidot, 75, recalling the historic Ice Storm of 1998. “Huge tree limbs and even entire trees crashed to the ground in explosions of sound all around our home.”

In the morning, when Pidot and his family ventured into their front yard, they found two towering tulip trees had been stripped of their branches. An avid gardener and environmentalist, Pidot was devastated.

“It took four of us all day to remove the debris,” said Pidot, a retired attorney who now lives in Brunswick. “It was an astounding experience.” An arborist told him the trees would have to be cut down, like thousands of others across Maine that were destroyed by the storm.

Twenty-five years after the Ice Storm of 1998, which peaked Jan. 7-9, Pidot and other Mainers harbor a mix of hard and happy memories from one of the state’s most destructive natural disasters. More than 100 people from across the state shared often detailed memories of the storm in response to a request posted by the Portland Press Herald, Sun Journal, Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel.

Downed utility lines blocked roads and cut electrical service to 80% of Maine’s 1.2 million residents at one point or another, according to the National Weather Service. Some lost power for more than two weeks in frigid temperatures.

Then-Gov. Angus King mobilized the Maine National Guard, and about 3,000 out-of-state utility workers rolled in to help restore electrical power. All 16 counties were declared federal disaster areas and 11 million acres of forest were decimated.

In total, the storm cost the state $320 million – more than $584 million today – and resulted in eight deaths: three from hypothermia, three from carbon monoxide poisoning, one in a roof collapse and one during tree cleanup, NWS reported.

A Farmingdale town official inspects ice damage to trees and power lines along Sheldon Street. Gordon Chibroski/Press Herald

Amid widespread school shutdowns, business closures and other interruptions of daily life, many struggled to stay warm and fed, stave off loneliness and overcome isolation. Some moved in with family or friends, others booked hotel rooms or stayed in one of 130 emergency shelters that opened across the state, often staffed by volunteers.

Gas-powered generators came to symbolize the best and worst in people in the wake of the storm. Many who had one shared their good fortune. Some who didn’t stole what suddenly had become a precious commodity. Bell Atlantic, the state’s largest phone company at the time, reported about a dozen generators were stolen from switching stations between Cumberland and Bucksport, cutting service to some customers until they could be replaced.

“I for one had a portable generator,” recalled Steve Martin of Arundel. “It was passed along among friends and acquaintances and neighbors just long enough to get their houses warmed up and keep the cold at bay. Everybody was good about refilling it and paying it forward. It worked out to about two to three hours for each house.”

Some relished going skating or ice fishing, taking photos of the icy landscape and “camping indoors,” where they cooked on wood stoves, read by candlelight and played board games with family and friends. Valamica LaBreck of Waterville was 11 years old at the time.

“I don’t remember how long we lost power for, but our friends had a wood stove, so we practically lived with that family,” LaBreck remembered. “Me and my friend played hours and hours of Monopoly by candlelight and I ate soup till it came out of my ears. I know that the ice storm was one of the worst storms in our state’s history, but for me it was a time of laughter, togetherness, games and talking all night under the covers.”

ICE STORM SLIPS INTO MAINE

Freezing drizzle started falling in southern and central Maine late Monday, Jan. 5, 1998, when Christmas lights still decorated many homes and businesses. On Tuesday, the weather service predicted more was on the way. When the rain finally cleared out on Saturday, 1.5 to 3 inches had fallen across the state, glazing every surface with at least 2 inches of ice and plunging more than 700,000 people into darkness.

For many, that also meant furnaces, appliances and well pumps didn’t work, so no heat, no cook stove, no refrigerator or freezer, no running water, no toilet. In freezing temperatures, finding someplace warm to stay became imperative, often with family members or friends.

Jewel McHale of Route 115 in Yarmouth cuts up one of the many trees that broke under the weight of the ice at her home. Although beautiful to look at, the ice storm caused a lot of damage to trees, wires and homes in the state. Gordon Chibroski/Press Herald

John Voyer lost power for four days in Portland’s North Deering neighborhood. He and his wife and their two teenagers drove to York to spend a couple nights with his sister-in-law, who had given birth recently. When it began to feel like they were imposing, they called a friend in Portland to see if they could stay with her for a while.

“She already had a house full of relatives from iced-in areas,” Voyer recalled. “(But) she was office manager at a primary care medical office and offered us the floor of the waiting room for shelter. We took her up on it and were grateful for a warm place to sleep.” They returned home the next day when power was restored at their house.

Drew Masterman and his wife hosted several of her relatives from the Augusta area for a week. That meant six people living in a one-bedroom apartment in Portland’s Parkside neighborhood.

“They arrived looking like refugees – scared eyes, with small children in tow,” recalled Masterman, who lives in Richmond. “Parking was difficult because the population of Parkside had doubled. All of Augusta was staying with their Portland friends.”

The sound of crashing trees kept Edna Swain awake Jan. 8 in Pumpkinville, an independent-living village in Cornish. Swain and other residents lost power at 2 a.m. Friday and Swain opted to stay in her apartment. Gregory Rec/Press Herald

Some ice storm escapees found more unusual accommodations.

Allisa Glasscock of Lewiston was a high school senior when classes were cancelled for about two weeks after the storm. When her older sister lost power at her home in Greene, she and her two young sons moved in with Allisa and their mother, who also had lost power but had a kerosene heater.

“I was working at Shaw’s in the bakery and they kept regular hours throughout,” Glasscock remembered. “I had my license and a car, so I worked, went ice fishing, stayed in an ice fishing shack on a lake and washed at friends’ houses.”

Debi Minton’s family “roughed it” for a couple of days after their electricity went out in Standish, then spent one night at a hotel in South Portland.

“Then, we packed up all our semi-frozen food and headed to family in Massachusetts,” said Minton. “On our way there, we saw all the out-of-state electric company trucks coming into Maine to help restore power. It was a good sight to see.”

DANGEROUS WALKING ON ICE

Icy ground made getting around difficult for everyone. Falling and crawling were common. So was seeing humor in the struggle.

On a farm in Freeport, Ann Brandt was without power for several days while her husband was traveling out of state and their two kids went to stay in Southport with her parents, who didn’t lose power.

She stoked the wood stove and drove around town, searching for water to fill 5-gallon buckets for their horse, pig, several sheep and chickens. Walking across the ice-covered farmyard was impossible.

“One of my strongest memories (is) crawling across the farmyard, dragging one bucket of water at a time over to the barn,” said Brandt, who lives in Portland. “Our house was up on a little rise from the farmyard, (so) I would just sit and slide down the little hill on my butt. Even at the time I had to laugh about how silly I must have looked.”

Brenda Buchanan lived on Peaks Island at the time. She remembers “shoe-skating” from her law office in Portland’s Old Port to the Casco Bay ferry terminal. She reeled from street signs to parking meters to utility poles.

“The brick sidewalks were crazy treacherous with thick, wet ice, and my route was downhill,” said Buchanan, who now lives in Westbrook. “I recall laughter bubbling inside me as I slid along. I was so lucky to make it to the boat, and eventually to my island home, without falling.”

Averyl Hill of Scarborough was one of about 4,000 Mainers who sought refuge in emergency shelters. She had recently moved back to Maine and was living in an apartment in Freeport’s village center. When her power went out, she heard that the First Parish Congregational Church was open.

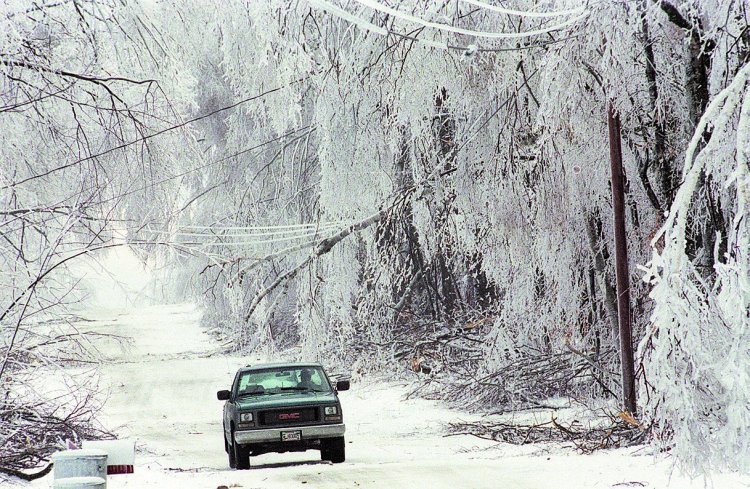

A car travels down Turner Street in Auburn flanked by broken trees and utility poles. Russ Dillingham/Sun Journal

“The sidewalks and steps leading down to the church were so icy that I had to crawl,” Hill recalled. “A lady with a big smile welcomed me and then went into the kitchen to stir a pot. Not long after we all sat down family style and shared a meal of hot soup. Everyone was so kind and warm.”

She spent the night in the church’s library, wrapped in a blanket donated by L.L.Bean, and read most of Harold Kushner’s “When Bad Things Happen to Good People” by candlelight.

Connie Hoffman, foreground, and Rita Darling, both of Fairfield, try to rest at the emergency shelter at the Colby College Field House on Jan. 9 during the ice storm. David Leaming/Morning Sentinel

RESPONDING DAY AND NIGHT

While thousands of utility workers were dispatched to repair downed poles and lines, the storm response enlisted help from other fields, including public safety, public works, home health and hospitality.

John Levesque of Waterville was on duty for 72 hours at Delta Ambulance in Augusta.

“We had ambulances off the roads and very limited ability to get far,” Levesque recalled. “It was the only time in my career that I ever was unable to reach a patient who called for help. After 30 minutes and only about 2 miles traveled, we had to turn around.”

Motorists had to take their chances driving under a tree that was resting on power lines on Route 5 in Limerick. Gregory Rec/Press Herald

Russ Lunt of South Portland worked for the city’s public works department, and cleared streets of ice and fallen trees for at least five days straight.

“We would sand and salt the streets, then try to scrape the excess ice buildup, over and over,” Lunt remembered. “Tree branches and trees were coming down at a never-ending pace. When we got a little ahead, myself and four other men and equipment were sent over to the city of Portland for two weeks to assist in their tree cleanup operation.”

Wil Whalen of South Portland was a dispatcher for a road service company. He worked long shifts, dispatching tow trucks across central Maine and taking naps in the break room. He was glad not to be driving a tow truck.

“When the tow truck drivers would stop by the main building to take a break, they looked like soldiers walking off the battlefield,” said Whalen, a combat veteran. “I may have worked 36 hours straight, but I did so in a building with power, heat and hot water. The drivers worked those long hours driving in the worst conditions possible helping everyone they could.”

Holly Lord of Portland was part of a team at VNA Homecare of South Portland that made sure nurses, physical therapists and social workers were able to visit patients living in storm-affected areas.

“We covered all of Cumberland County and knowing what roads were open and which were closed was vital,” Lord remembered. “We had a big board in our lobby listing all the closed roads as we heard about them.”

Even restaurant and hotel workers put in extra effort for people in need of food and shelter. When power went out in Orono, Pat’s Pizza kept churning out pies for hungry people thanks to a generator and several large propane tanks, recalled Bill Jeffrey of Wells and Scottsdale, Arizona.

Maureen LaSalle of Portland was working at a hotel that lost power. “All of the managers had to pitch in to bring buckets of water from the pool to guest rooms to flush toilets,” she remembered. “And we had nine floors without elevators. Talk about getting your steps in.”

HOSPITALS FILL UP

Hospitals were crowded with people needing treatment for hypothermia, falls and carbon monoxide poisoning. Some people were there because their oxygen pumps and other medically necessary equipment ran on electricity.

Gil Fraser of New Gloucester lost power at home for 11 days, yet he felt compelled to get to work as a pharmacist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

“I went prepared for any contingency,” Fraser recalled. “My car was packed with a chainsaw and crampons in case I needed to clear a path on a slick road. Fortunately neither tool was necessary as I made my way to the hospital.”

Tom Gyger of South Bridgton works with his tractor to clear a path down Route 107 as he spearheads a rescue effort to help Mac Gillet get out of his remote home at Moose Cove on Jan. 9. David A. Rodgers/Press Herald

Millie McDonough of Brunswick brought a sleeping bag to work at Southern Maine Medical Center in Biddeford and put in extra hours to keep up with medical transcription services. Johanna Dumas of Lewiston was working as a radiologic technologist in 1998 and remembers using portable X-ray machines and developing X-rays by hand.

“Many long days, for sure,” Dumas said.

Sara Orbeton of South Portland was a nurse at Mercy Hospital in Portland and filled a few shifts for others who couldn’t get to work. Between shifts, she found an empty room to catch some sleep.

“I was able to get clean scrubs from the hospital, so I didn’t have to wear the same clothes for three shifts,” Orbeton recalled. “By the time I finished that last shift, most of the ice was melting and I could get home.”

OLD-FASHIONED COMMUNICATION

Without electricity, modern means of communication and home entertainment fell silent for many.

Maine Public Television and Radio were unavailable to most viewers and listeners for more than a week, according to the Maine Emergency Management Agency. Other commercial radio and television stations in southern and central Maine lost communication towers or electrical power and were unable to broadcast. Even the Emergency Alert System failed.

Doris Cram gets a helping hand from Vinal Goss as she walks back to her apartment after power was restored to Pumpkinville, an independent-living village in Cornish. Gregory Rec/Press Herald

It also was the early days of the internet, so Facebook and other social media weren’t available yet. People used newspaper classified listings to offer or ask for assistance and items greatly needed after the storm.

“We had two wood stoves that we had removed from active use when our children were little,” recalled Leslie Nicoll of Westbrook. “We listed them in the paper and they were snapped up in hours.”

Radio stations that were broadcasting provided a lifeline for many, who listened on battery-powered equipment. Some stations aired messages from people who had run out of firewood or needed help clearing icy steps.

“The radio was our connection with the outside world,” said Constance McCarthy of Northport. “There were stations that ‘talked to us’ all night, which was helpful and let us know help was coming from other states.”

People who lost power for long periods posted desperate hand-written signs such as, “Please Help CMP, No Power.”

Listen to Gov. King’s 1998 State of the State address:

Reading to each other was no longer reserved for parents and their kids.

“Our widowed neighbor came across the road and spent time sitting around the stove with us as we read to each other in the evenings after a shared meal,” recalled John Clark of Waterville.

FENDING FOR FOOD, WATER AND POWER

For those roughing it at home, hauling water, preparing meals and accessing power became priorities.

People who lived near a lake or stream would lug buckets of water to flush toilets. Potable water was available at fire departments and other public buildings. Many businesses encouraged employees to fill water jugs and wash up at work. Family members and friends opened their homes to those in need of a shower.

Toby Winkler, 13, gets water from a hole in the ice of Pettingill Pond. Winkler takes the water back to his home on Angler Road in North Windham to use when flushing the family toilet. John Ewing/Press Herald

“I was a junior at Jay High School at the time and after a few days of not showering, I put on my old cross-country skis and skied across town to my girlfriend’s house,” Justin Easter of Vienna recalled. “They had a generator and hot water. That was one of my most memorable skis, with the sound of the trees cracking and being able to ski down the middle of roads.”

Anthony Winslow of Gray cooked on an outdoor grill for 12 days. He and his wife lived in Durham at the time.

“You run out of things to create on a small gas grill at around Day 5,” Winslow said. “I also remember the contents of our fridge and freezer being on our small back deck.”

Diana Nadeau and her husband had a half-side of beef in the freezer when the power went out. They had saved up for the purchase and didn’t want to lose it.

“We put some outside in coolers to save our investment,” said Nadeau of Andover. “We had a kerosene lantern and a Coleman camping stove. We had some great meals of T-bone steaks and ribeyes for supper by the light of that kerosene lantern. We lost power for five days but managed to keep all that expensive meat.”

Many people throughout Washington County lost the meat stored in their deep freezers after the power went out. Adam Thompson of Cape Split in South Addison resorted to storing his meat outside under chunks of ice, which was in plentiful supply. Gregory Rec/Press Herald

Alison Jacobs of Lewiston remembers sharing meals with neighbors.

“Whoever had something thawing that needed to be eaten, we would add that to the meal and share all around,” she said. “Those of us with a wood stove were able to cook basic meals and then those with a generator would brew the always important coffee and share.”

Sharing or buying scarce generators was a solution for many Mainers.

Jennifer Jones was a newlywed living in a renovated farmhouse in Vassalboro. After three days without power, she drove to the Home Depot in Bangor, stood in line for three hours and paid budget-challenging $329 for a generator.

“Nothing sounded better than the whir of that generator and the joy we felt to have heat and electricity,” Jones recalled.

When the power went out recently at their current home in Falmouth, her husband fired up the same generator.

“We have used it nearly every winter since that dreadful ice storm in ‘98,” Jones said. “It still brings amazing comfort when everything goes dark.”

While some shared generators, others ran extension cords from house to house.

Steve Wanzer allowed two neighbors share an outlet in his garage in Portland. During the day, one neighbor would plug in his chest freezer to keep food from thawing. At night, the other neighbor would plug in his furnace to warm his house.

“The next morning the process (repeated) itself,” Wanzer recalled. “It brought all us neighbors closer.”

KIDS STILL HAD FUN

Many who were kids at the time have fond memories of school being canceled, skating on icy lawns or driveways and playing games for hours on end. Some families ventured out to see the now-classic film “Titanic,” which had opened just before Christmas.

Roger Pelletier was 11 when he woke up in a freezing cold house in Auburn. For the next 12 days, his family of five moved in with an aunt who lived across town and never lost power. An uncle’s family of five joined them.

“We spent day after day watching her endless supply of Disney VHS tapes,” said Pelletier, who lives in Caribou. “On the 12th day of no power, I went with my parents to check out our home. I remember going into the basement and them flipping the furnace on, and it actually turned on. I can remember the sound of it churning up, and I remember everyone being so happy the power had been restored.”

Barrett Littlefield of Bath remembers his whole family sleeping in one room and cooking dinner on a wood stove. He was 12 at the time.

“When the electricity still wasn’t on after a few days, my siblings and I were shipped off to the homes of relatives who did have power,” he recalled. “Board games, cribbage tournaments and cable TV were much better than school. I had no awareness that, for many, the ice storm was a traumatic event.”

Gina Campbell was 9 when the storm cut power to her family’s home in West Falmouth. She remembers worrying that her newborn sister might die from exposure and going to stay in Portland with her grandmother, who didn’t lose power.

“When I found out my cousins were staying at the DoubleTree Hotel on Sewall Street, I begged my parents to let me stay with them,” said Campbell, who lives in Portland. “I ended up living the high life with an indoor pool and room service for five days before we got our power back.”

LIFE GOES ON

Under all the layers of ice, some aspects of life went on as usual. Families went ahead with concert plans and birthday parties, despite treacherous travel conditions and lack of heat and lights.

The storm didn’t stop Brianna Harger and her stepmother from attending an Aerosmith concert on Jan. 7 at the Cumberland County Civic Center in Portland. They drove down from Readfield that day in a 1992 Toyota Corolla.

“Steven Tyler did not disappoint and I’ll remember it forever,” Harger said. “At the end of the concert Steven said, ‘I hear it’s getting quite nasty out – you all be safe out there.’ It took us over four hours to get home.”

Henry and B.J. Kennedy of Cumberland hosted a pizza party sleepover for their daughter’s 9th birthday. The kids made a giant nest of comforters and stuffed animals in the living room heated by a wood stove. The party continued for five days.

“Everyone was having a blast even though the power went out,” Henry Kennedy recalled. “The kids were warm and safe, so the party continued when school kept being canceled. The girls are still great buddies.”

Eric and Polly Bartlett read by the light of a Coleman lantern in their home in Casco during the Ice Storm of 1998. Photo courtesy of Eric Bartlett

Rita Thompson of South Portland served at a funeral at Holy Cross Church while the power was out. “I couldn’t get out because a tree blocked our dead-end street,” she recalled. “The woman that was serving with me picked me up on the next street.”

Ivy Frignoca’s son took his first steps during the ice storm. Their home in New Gloucester was without power for nearly two weeks.

“I will never forget stoking the wood stove and turning around to see my baby stand and walk over to me,” said Frignoca, who lives in Cumberland Center.

THE END IS NEAR

Recovery from the storm came in stages. Power was restored neighborhood by neighborhood, town by town.

People celebrated each step toward normal life. Frank Heller of Brunswick described the storm’s end as “an almost Biblical event.”

“The sun came out and melted inches of ice on trees covering the outdoors with a coating of diamonds,” Heller said. “We cheered with the neighbors in amazement.”

Eric and Polly Bartlett of Casco got their power back after three days of keeping warm with a kerosene heater, storing food outside in coolers, listening to news on a small transistor radio and reading by Coleman lantern.

“Never were we so glad to hear the fridge humming again, be able to watch TV, and go about our normal lives,” Eric Bartlett recalled.

Barbara Alexander of Hallowell remembers when utility workers from Nova Scotia rolled down her street.

“The entire neighborhood came out to offer them coffee and treats,” she said.

Jeff Pidot is a retired lawyer who lived through the great Ice Storm of 1998, which devastated two massive tulip trees in the yard of his former home in Hallowell. Ben McCanna/Staff Photographer

In Hallowell, Jeff Pidot took the arborist’s assessment to heart but decided to delay cutting down his stripped tulip trees.

In June, both trees exploded with branches and leaves.

“I was shocked and so happy that I cried,” Pidot said. “The arborist returned and was awed. Within three years, the trees were fully restored. The resilience of nature is miraculous.”

So too is the resilience of Mainers.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.