They talked of being sent to the remote woods in below-freezing weather with little gear as punishment for their attitude, of being forced to shovel snow or build a road instead of going to class, to “confess” their sexual abuse, be confronted in group therapy sessions and told to report other students’ misbehavior.

Eight former students of the Hyde School recounted those experiences and more to the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram in interviews conducted over the past five months. They said they went through varying levels of physical, emotional or sexual abuse at the school’s campuses in Maine and Connecticut. They spoke of a culture of shame and blame and argued Hyde’s tactics had lasting negative effects on their mental health and the trajectory of their lives.

“I feel like it’s child abuse for hire,” said Emma Siegel-Reamer, who attended Hyde’s Connecticut campus in 2003.

Hyde was first established as a private boarding school nearly 60 years ago and markets itself as a college-preparatory, character-building program. Its mission, according to the school website, is to “develop character to discover unique potential.”

Most of those interviewed by the Press Herald have been working with attorneys to bring a civil complaint.

Jessica Fuller, a former student, filed a federal lawsuit Friday against the school and several of its leaders in U.S. District Court in Maine alleging they violated human trafficking, forced labor and negligence laws, while making millions of dollars in revenue.

Fuller is the only named plaintiff but her attorneys are asking the court to grant class action status, arguing more than 100 students had similar experiences and should be included.

“Our argument is that Hyde allowed and even encouraged and participated in, at times, abuse of children, whether that be emotional abuse, physical harm, sexual abuse, hard labor,” said Kelly Guagenty, an attorney with Justice Law Collaborative, a firm in Massachusetts that filed the lawsuit alongside the Maine-based Island Justice Law.

In a Friday letter to the Hyde community shared with the Press Herald, Board of Governors President Dana McAvity said many other students and families had positive experiences at the school and that the allegations “grossly mischaracterize Hyde’s policies and practices over time or are patently false.”

“Hyde vehemently denies these claims and intends to vigorously defend itself, its reputation, and the character education model that makes Hyde the special and effective school it is,” she wrote.

Over the past several years, advocates have been working to increase awareness of problems within the nationwide network of boarding schools and programs for troubled teens, sharing survivor stories from the largely unregulated billion-dollar industry. Celebrity heiress Paris Hilton, herself a survivor of a Utah-based program, has lobbied Congress to increase federal oversight of the private facilities.

The former students who spoke with the Press Herald attended Hyde’s two boarding campuses between 1996 and 2014. Most believed they were going to a traditional boarding school that was supposed to set them up for success. Instead, they each said, they walked away with formative experiences that changed the course of their lives for the worse.

· · ·

“We already have the criminal justice system and we have the mental health system. We don’t need these individual, privatized schools with no regulation doing whatever they want with minors in their custody.” – Rachel Deadman

· · ·

Not all of them are directly involved in the litigation. The lawsuit is seeking class action status for any students who experienced forced labor at the school since July 2015, and any who were minors who have not yet turned 28, due to statute of limitations. The attorneys are also asking the court to certify a bigger class that also includes anyone who attended the school but did not come to realize the extent of its harm until later in life, under a legal doctrine known as discovery rule.

The reasons students who spoke to the Press Herald were sent to Hyde varied. Some struggled academically, or needed more “structure.” Some were doing drugs, had fallen in with the “wrong crowd,” had run away from home, had gotten in fights with their parents. Others had experienced sexual assault, or had anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder or clinical depression.

Many former students interviewed argued places like Hyde shouldn’t exist. The lawsuit asks the court to immediately intervene to prevent the school from forcing any students to perform labor.

“We already have the criminal justice system and we have the mental health system,” said Rachel Deadman, who attended Hyde’s Connecticut campus starting in 2005. “We don’t need these individual, privatized schools with no regulation doing whatever they want with minors in their custody.”

‘The Hyde School Difference’

Hyde School was founded in 1966 by Joseph Gauld, a 1951 Bowdoin graduate who worked as a teacher and administrator at a boarding school in New Hampshire and at Berwick Academy in Maine before realizing he was “envisioning change beyond what the system could or would absorb,” according to his 1993 book, “Character First: The Hyde School Difference.”

He purchased the estate of a Bath Iron Works founding family and Hyde was born. The 145-acre wooded campus off High Street is centered around a 1913 brick Georgian mansion.

Concerned about an overemphasis on academic achievement and giftedness in other boarding schools, Gauld said he wanted his institution to concentrate instead on the character and unique potential of each student, with a core focus on parental involvement.

Gauld publicly wrote about his unorthodox methods, and in a 1973 column published in the Maine Sunday Telegram titled, “Slap May Be Just What a Child Needs,” he recounts hitting a prospective student three times and chasing her around campus during an interview.

A 1976 Time magazine story says Gauld “occasionally slaps and routinely humiliates the kids” and describes punishments like trench-digging and public paddling. Time reported that he liked to say: “The rod is only wrong in the wrong hands.”

In a Times Record article responding to the Time story, Gauld called it “cynical” and said it didn’t capture the full picture of the school, where he said for every act of discipline, there are several acts of affection.

Hyde attracted some notable names over the years. “Character First” features a foreword from the singer and actress Cher, whose youngest son Elijah Blue Allman attended the school in the early 1990s.

A later book written by Gauld’s son and daughter-in-law includes a foreword by the children’s book author Marc Brown, who created the popular PBS show, “Arthur.” His two sons went to Hyde. Former Press Herald owner Reade Brower told Down East magazine that his children also attended the school.

Gauld attempted to build on his early momentum and roll out a program following his philosophy at Gardiner Area High School in the 1990s, which quickly fell apart after meeting resistance from teachers. He founded partner charter day schools around the country, some of which have since closed. In 1997, the school opened a second campus in Woodstock, Connecticut, which sold in 2017.

The original campus in Bath currently enrolls about 135 students, according to a September 2024 filing with the state. Annual tuition costs $68,300.

It also is approved as a public tuition receiver, allowing it to enroll students who live in parts of the state that don’t have their own designated high school, and collect some tuition money. Only one student currently attends the school under that program, according to Maine Department of Education data.

Gauld died in 2023. His son, Malcolm Gauld, attended and later led the school.

Malcolm outlined some of the school’s philosophies in a 1992 essay titled “Discipline at Hyde School” that was published in a book alongside other writings about boarding school policies. In it, he described the school’s approach to rule-breakers: those students should be pulled out of classes, sports and activities and put on a work crew.

Many would resist.

“The fact that many students consider this cruel and unusual punishment says more about our society than it does about Hyde School,” Malcolm Gauld wrote. He now directs the Hyde Institute, while the school is run by his wife, Laura, herself a Hyde alumna.

One of the school’s core principles, the Gaulds wrote, called Brother’s Keeper, dictates that if one student witnesses another break a rule and doesn’t turn them in, they’ll receive the same punishment.

Students from the Bath campus recall having to chant a motto that hung on a plaque outside the dean’s office: “The truth will set you free, but first it will make you miserable.”

The lawsuit alleges that Hyde enticed parents and students under the premise of innovative education, and advertised itself as “fundamentally different from other boarding schools and therapeutic programs” but that that marketing downplayed the practices at the school.

“This lawsuit seeks justice for the hundreds of students who were trafficked, abused, and exploited by the Gauld family’s systematic child labor scheme operating under the false promise of character development and innovative education,” the complaint reads.

In her letter to the school community, McAvity said Hyde students harness their strengths in an “environment of remarkable support” and said the school’s “unique ingredients” have produced life-changing results for thousands of students.

In recent online reviews, dozens of parents and former students describe positive transformational experiences at the school, praising its character-based philosophy and parental involvement.

“As proud as we are of this history, we know that not all of our former students and families feel positively about Hyde. We pay attention to all feedback, whether positive or critical, which has contributed to our continuous improvement,” McAvity wrote.

The lawsuit alleges Hyde is a participant in the troubled teen industry, a label the school rejects.

Dr. Heather Mooney, a social scientist who studies troubled teen programs, said therapeutic private boarding schools can sometimes be mistaken for traditional boarding schools, especially in New England.

She pointed to the elite, college-prep John Dewey Academy in western Massachusetts, where allegations of shame-based therapy and sexual assault led to its closure and rebranding.

Mooney said these types of schools can be an appealing alternative to juvenile detention or inpatient programs for upper-middle-class parents, but “totalistic programs” have characteristics distinct from a traditional school, like a need to change the whole person, peer surveillance and group confrontation rituals.

“The lack of oversight and regulations has allowed this really harmful, snake oil industry to proliferate, and prey on scared families that are generally dealing with pretty normal (things),” said Olivia Stull, a doctor of counseling psychology in Arizona who wrote her dissertation on troubled teen programs.

Ineffective therapies

Frederic Reamer enrolled his daughter, Emma Siegel-Reamer, at Hyde in the early 2000s. Reamer, who taught social work at the Rhode Island College, thought she could use a bit of structure, and heard about the school thirdhand.

But when he visited the Connecticut campus during a parents’ weekend in the fall of 2003, he quickly decided to pull his daughter out (she opted to finish out the year before transferring to another school).

He was immediately off-put by what he described as a cult-like environment with unqualified staff. He was unnerved by what he saw as Joseph Gauld’s “narcissism” regarding his own educational tactics, and he was astonished that the school, which heavily enrolled students with mental health issues, substance use disorders and traumatic histories, did not have a therapist on staff.

Some students who came into Hyde needing services like therapy or drug rehab say they had limited options. The lawsuit alleges students were threatened with punishments for, “reporting medical conditions, asking for psychological help, running away, threatening to run away, asking for medicine, or refusing medicine.”

Siegel-Reamer said she was seeing a therapist off-campus until a teacher threatened to “make her life a living hell” for showing up late to class as a result.

Reamer and his wife, Deborah, also a social work professor, published a critical article in 2004 about their experience as Hyde parents. They wrote that they chose the school because of its promises of accountability, family involvement and integrity. But once their daughter was inside, they observed a lack of specialized support, shaming and name calling of students, poor handling of mental health issues and misleading engagement with parents.

“In our experience, many Hyde staffers were unfamiliar with, or dismissed, prevailing research-based theories and practices for helping struggling teens,” the article reads. “We found a dogmatic adherence to what’s called ‘the Hyde process,’ even when the process wasn’t working.”

Former Hyde students who were interviewed say central to that process was group “attack therapy” sessions.

They remember being split into small groups to frequently meet with a school staff member where they say they were required to confess their wrongdoings. The lawsuit alleges these sessions involved students admitting “traumatizing and embarrassing facts to their peers, often from a stage to a large group” after which “staff and peers scream verbal attacks at them.”

· · ·

“We found a dogmatic adherence to what’s called ‘the Hyde process,’ even when the process wasn’t working.” – Frederic Reamer

· · ·

Deadman, who attended Hyde’s Connecticut campus starting in 2005, talked about a time when a classmate confessed to sexually abusing his sister, after which he was praised for his honesty. Others said they felt forced to confess to misdeeds like smoking cigarettes or having sex just to satisfy the group leaders, even if they weren’t true.

After being pressured to disclose sensitive information, Reamer wrote in his article, students would be called “manipulative,” “drama queen,” or “quitter.”

Guagenty, the attorney, said some of her clients who had past sexual trauma were forced to disclose that they were sexually assaulted or abused by their parents. The lawsuit says Hyde would “punish any student who refused compliance. Punishment includes excessive exercise and forced labor.”

“Instead of working with that student to process and provide them proper mental health care, they were put in a room and attacked,” Guagenty said. “Meaning the group would be encouraged to tell that survivor, ‘This is what you could have done differently to not make that happen,’ or, ‘This is your fault.’”

During parents’ weekends, former students said, adults joined the group sessions and were bound by the same rules. Sometimes parents were pressured to reveal publicly to their children that they were having an affair, or to come out as transgender.

“If you didn’t self disclose, you were confronted,” Reamer said. “I mean, confronted. ‘What are you hiding? Why aren’t you willing?’ That kind of stuff. And this from people who, to be blunt, really didn’t know what they were doing.”

Reamer said he met parents who seemed all-in on the Hyde philosophy but also met plenty of skeptics.

In interviews with the Press Herald, several former students described continually strained relationships with their parents after leaving Hyde, decades-long disagreements about the value of the school and the severity of its impacts. Some argue their parents were misled, in various ways, about the school’s true nature.

“We’re not the school the kids want to go to,” Malcolm Gauld is quoted saying in a 2005 Education Next article. “We’re the school the parents want the kids to go to.”

‘Out to Work’

All of the former Hyde students interviewed said physical labor was a mainstay of life at the school, and what leaders characterized as discipline, the plaintiffs’ attorneys argue “was essentially hard labor and free labor.”

The lawsuit alleges that Hyde “profited from the forced labor of Plaintiff and Class Members.”

Students were often put on what was called “2-4” or “out to work,” where they were not allowed to make eye contact or socialize with other students. They shoveled snow, built roads, scrubbed toilets, washed cars, raked leaves, built structures, landscaped and cleaned dorms, the lawsuit alleges, and some of that work was performed at staff and Gauld family homes.

According to interviews and the court filing, students on 2-4 sat at a special table in the dining hall, segregated from the rest of the student body, and had to eat different food from their peers — some students recalled only being allowed peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.

While they were on 2-4, which sometimes lasted weeks, students said they didn’t go to class.

In his 1992 essay, Gauld wrote that when 2-4 doesn’t sink in, students will be taken to a wilderness site or island, given camping supplies and asked to fix their attitude.

“If you continue to exhibit the attitude which brought you here, you will remain out here indefinitely,” Gauld wrote, adding that the trips often lasted a week to 10 days, but could go longer based on the attitudes of the group.

Sometimes students were sent to Seguin Island off the coast of Popham Beach in Sagadahoc County.

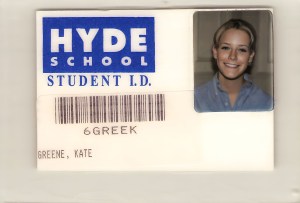

Former students like Kate Greene, who attended Hyde beginning in 1996, said they spent their time there clearing trails with hedge trimmers in total silence, or doing sprints.

Other times, the lawsuit states, students were sent to a remote camp in Eustis, a small town in the western part of the state where Hyde owns a piece of property now called the Lenox Outdoor Leadership Center.

Deadman, who was enrolled at the Connecticut campus but spent weeks at the Eustis outpost, said they were provided little winter weather gear despite blizzard conditions, and at night students were blindfolded, walked to different areas and left alone to pitch a tent.

During the day, she said, they mostly chopped wood in silence, still forbidden from speaking to one another.

There was limited food to sustain students during the manual labor, the suit alleges.

“It’s to break the human spirit, really,” Deadman said.

Some say they suffered physical harm as a result of 2-4, wilderness trips or required military-style workouts, and that injuries incurred through these activities — including severe frostbite, strained muscles and asthma attacks — weren’t taken seriously or treated in a hospital. Guagenty said many of her clients also cited improper restraint and physical abuse by staff.

A woman who attended Hyde’s Connecticut campus in 2005 said she was sent to Eustis in January in below-freezing temperatures after other students accused her of starting an argument. She said the school called her mom and described it as a character building trip, not mentioning that it was a punishment.

After two weeks, the woman, who asked not to be identified, said she got tendonitis in her Achilles tendon and was allowed to return to campus. She said that injury still troubles her today.

Sexual misconduct

Kate Greene was sent to Hyde’s Bath campus in 1996 after being sexually assaulted at her high school and entering a state of depression.

Greene got in trouble for running away with some of her classmates. After returning, she says she was called to the dean’s office, where an administrator called her a slut, and on her way out the door, he pushed her up against the door and choked her.

The lawsuit alleges administrators frequently called students sluts and other gender-based and racial slurs.

Former students interviewed described peer-on-peer abuse that resulted from poor supervision at the school, inappropriate relationships between adults and minors, and sexual relationships between students and staff, all of which was common because many employees were recent alumni of the school, barely older than students, they said. “In multiple instances, student proctors coerced Class Members into performing sexual acts by threatening continued forced labor and physical harm if they refused,” the suit alleges.

Those types of allegations have played out in other civil cases filed against the school.

In a pending lawsuit in Connecticut, a plaintiff identified as Jane Doe alleged that in 2005 during the school’s summer program two male students sexually and physically harassed her in the middle of the night and that school staff failed to prevent or intervene in the incident.

She accused the school of negligence and hiring of unfit staff. That case is set to go to trial in September.

Hyde settled a separate lawsuit in 2003 with a former student who accused a male teacher of sexual misconduct, in which she said the school ignored her mother’s requests to keep the teacher away from her daughter.

Some former students say their concerns about sexual harassment were ignored or downplayed by administrators.

Julie W. attended Hyde’s Bath campus in 1997 and asked to only be identified by her first name because of privacy concerns. She said that while at Hyde a male student approached her in a classroom where he exposed himself and sexually harassed her.

She told a female administrator, who pointed out that Julie had “messed around with a few boys” at the school. Julie said the administrator told her that if she were in a similar situation, she would have pushed the harasser away.

Julie said she was sent to the wilderness outpost in Eustis for five days for that incident.

“I’ve had way worse things happen to me since Hyde,” she said. “But it was just the way it was treated, the way she implied that it wasn’t that big of a deal because I was a slut anyway.”

Measuring academic success

According to Hyde’s website, 100% of students in the class of 2022 were admitted to a four-year university. But former students said getting into college and succeeding there are different matters, and the academic foundation they received at Hyde was severely lacking.

According to the 2005 Education Next story, Hyde students’ drop-out rate at the time was about 40% per class. Former students interviewed for this story describe lacking knowledge in foundational subjects like math, history and biology, and difficulty advancing in their chosen fields or in higher education.

They entered Hyde as academic overachievers, they said, and left underprepared, insecure and unmotivated.

For some of those interviewed, that’s the root of their involvement in the legal action.

“While Hyde marketed itself as an academic institution, its curriculum was secondary to its labor and disciplinary systems,” the suit alleges.

McAvity said Hyde’s philosophy and curriculum have been consistently accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges since 1970. “Of the 2,500 graduates of the Maine campus, 96 percent were admitted to accredited colleges,” she wrote.

Interviewed former students say they missed out on substantial learning because of 2-4 or discipline trips, that Hyde’s effort-based grading system inflated their report cards but left them underprepared for higher education, or that getting into college at all was a struggle because of a diploma withholding system called “senior evals.”

Some former students who were interviewed said their peers got to vote on whether they received an official diploma, or another paper called a “document.” Which distinction students received was decided purely on other students’ personal opinions of them following a “public airing out of what everyone hates about each other,” according to one student who attended Hyde’s Connecticut campus beginning in 2010 and asked not to be identified out of privacy concerns.

He said he was unable to get into any colleges after his classmates wouldn’t give him a diploma. More than a decade later, after threatening to sue, he said the school mailed him one, but the damage had already been done.

Hyde leaders did not answer specific questions about this diploma process, and pointed to McAvity’s statement.

‘Hyde cuts very deep’

In his book, “Character First,” Joseph Gauld quotes an anonymous Hyde graduate reflecting on the school.

“Any student who’s ever gone there ends up feeling strongly about it one way or the other,” the quote reads. “Hyde cuts very deep.”

Most of the former students interviewed for this story said they experience post-traumatic stress disorder, suicidal ideation or major lapses in memory. Many said their time at Hyde permanently altered their sense of self.

Emma Siegel-Reamer, the daughter of the social work professors, said most of the people she knows from Hyde are struggling in adulthood.

“I never thought of myself as a bad kid. And when I went there, that label was put on me, and it was just beaten into my brain that I was bad,” Siegel-Reamer said. “I deserved what I was getting. And I adopted that persona, because I truly believed that’s who I was.”

All of the former students who spoke with the Press Herald about Hyde recalled close friends from the school who died as young adults. Many describe times they considered or attempted suicide, or say they self-harmed for the first time at Hyde.

“I used to think, if I write a suicide note, Hyde will be my No. 1 thing I’m blaming,” said Julie W., the student at the Bath campus. She says she was struggling with her mental health at the time and was shamed and attacked by the school and her peers for being withdrawn. “Because that’s the thing that just never leaves me.”

In an online forum, survivors have compiled a list of more than 160 Hyde attendees who died after leaving the school, most of them under the age of 30. The list links to obituaries for most of the students, which show they often died of suicide or a drug overdose.

Greene, a thorough documenter of her experience at Hyde, keeps an annotated list of her classmates from 1997-98. She updates it each time another one passes away. Currently, she believes out of about 100 students, eight are dead and one is missing.

Angie G., who was at the Connecticut campus from 2011 to 2014, said she can think of 14 classmates who have died. That’s more than the number she said have died from her public high school student body of 2,000 students, she said, compared with Hyde, which enrolled less than 200.

Angie, who asked not to be fully identified, said she has a close friend who was visibly self-harming throughout his time at the school. He died by suicide three years after leaving.

“My biggest qualm with Hyde is that they were aware that people needed some serious treatment, and they would not do it because they wanted to collect their paychecks,” she said. “So much got overlooked, and once I left, people started dropping like flies.”

· · ·

“So much got overlooked, and once I left, people started dropping like flies.” — Angie G.

· · ·

McAvity called those accusations egregious and offensive. “This narrative is not only false, it preys upon vulnerable families,” she wrote, noting that only two students have ever died while enrolled at Hyde. “Our hearts go out to all families who have lost loved ones,” she wrote.

“Contrary to the allegations made in the lawsuit, Hyde considers its obligations to protect students to be paramount,” McAvity said. “We stand behind our school leaders and believe that they have worked tirelessly to do the right thing for our students.”

Many former students have been drawn to online communities — some after coming across documentaries like 2020’s “I Am Paris,” about Hilton’s experiences at therapeutic schools, or Netflix’s “The Program,” about a now-defunct troubled teen facility in upstate New York — where they’ve connected with other former students, traded stories and realized they aren’t alone.

“I was like, ‘I wonder if there’s other people out there who are still as fucked up about Hyde as I am,’” Julie said. “And I went looking for them and found a lot, and it gave me a lot of validation. Because you spend most of your life blaming yourself for the things you didn’t accomplish there, or all the criticism they gave you.”

The Press Herald obtained several records of recent complaints sent to the Maine Department of Education that suggest concerns persist at Hyde.

In 2022, a mom wrote that she was concerned her son was being retraumatized in attack therapy sessions, and being forced to do manual labor outside in freezing temperatures without sufficient winter clothing. She worried about him not being able to get his diploma and graduate early like he wanted. She could not be reached to discuss the allegations.

In October 2023, a Hyde student submitted an anonymous complaint to the Bath Police Department, concerned that the school was breaking laws and that faculty were not equipped to run a “mental aid boarding school” and asked police to send an investigator to “witness the atrocities that occur.”

“I am a fully sober, sane, and reasonable student, and I am helpless to watch as all the children around me are abused,” the student wrote.

Bath police said they reached out to the student, whose name is redacted in its records, but didn’t hear back, then forwarded the case to the state’s Education Department. A department spokesperson said private schools are out of the agency’s realm of authority and so it would not investigate, but would refer complaints to the state Department of Health and Human Services.

A DHHS spokesperson said they have no record of conducting any investigations, but did say the department has received a number of complaints about the school over the years.

The civil case could take years to resolve. Both Hyde leaders and the plaintiffs’ attorneys have acknowledged that pre-litigation talks were ultimately ineffective.

In the filing, the attorneys requested a jury trial and asked the court to immediately intervene in Hyde’s operations by seizing all of the defendant’s assets, preserving all documentation and ordering the school not to allow any students “to engage in forced labor or labor performed under threat or coercion.” They are also asking the court to award them compensatory and punitive damages.

As of Saturday, no hearings had been scheduled and Hyde’s legal team had not filed a full response.

If you are a former Hyde School student and would like to share your experiences with a reporter, please reach out to Riley Board at [email protected].

IF YOU NEED HELP

IF YOU or someone you know is in immediate danger, dial 911.

FOR ASSISTANCE during a mental health crisis, call or text 888-568-1112. To call the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, call 988 or chat online at 988lifeline.org.

FOR MORE information about mental health services in Maine, visit the website for the state’s chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, call the NAMI Maine Help Line at 800-464-5767 or email [email protected].

IF YOU or someone you know has experienced sexual violence, you can call 1-800-871-7741 for free and confidential help 24 hours a day.

OTHER Maine resources for mental health, substance use disorder and other services can be found by calling 211.