This is a speech that my great grandfather, Walter, wrote around 1966 or 1967 when he was 90 years old. In it, he captures what life in Maine was like more than 100 years ago, from working log jams on the Kennebec River to selling the first Model T Fords ($440!) and Buicks in the community. There’s also an eyebrow-raiser about him evading arrest during World War I.

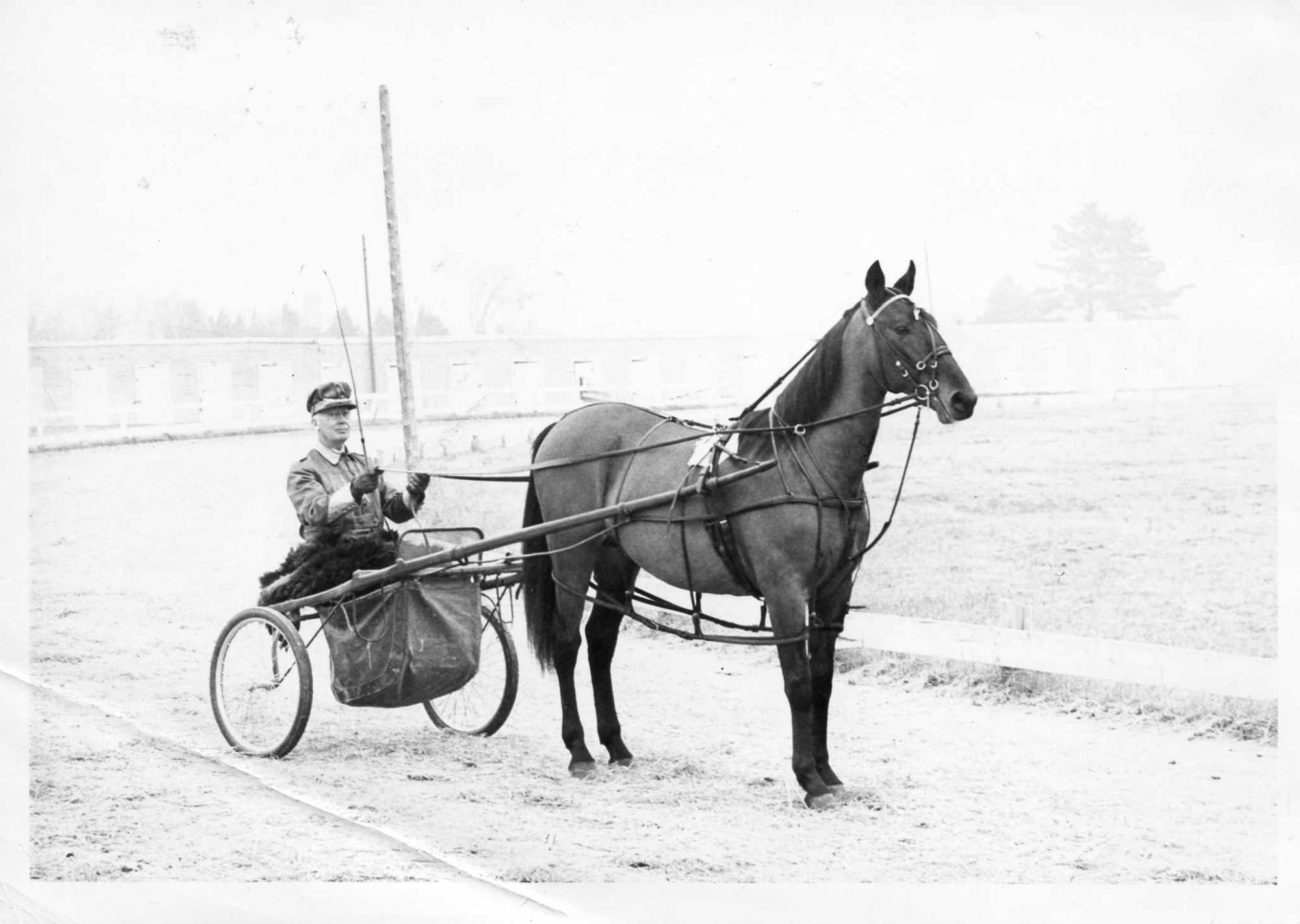

To me, this is a fascinating ride through both the Hight family’s history and local history. We see how quickly technology changed—Walter grew up in the late 1800s with water pipes in the home made of wood, which was a luxury itself, and also describes having an early electric car model in 1910 or 1911. I also couldn’t help but be reminded of the COVID-19 pandemic when Walter describes contracting smallpox and the small (though inconsequential!) public health scare he caused. You’ll also find some details about the racehorses Walter brought home from Kentucky, part of our family’s long involvement as boosters of the Skowhegan State Fair. My great grandfather kept his stable on the fairgrounds.

We’ve edited it here for length, but it’s otherwise as Walter wrote it. If his stories bring up your own memories, I invite you to share them with us, or visit our Hight Chevrolet Skowhegan Showroom, which has walls of old photos, newspaper articles and advertising. Hight Ford also has old photos and there are antique cars in the showroom.

I was born (December 12 1887) on a farm in Norridgewock, and lived there until I was 20. It was a good farm home. We had about 350 acres of land which was crossed by the Somerset Railroad. Father sold them 100 cords of four-foot wood each winter, as the engines in those days burned wood to make steam. It was not the day of the diesels.

Water for our house, our barn, and our stable was piped from a spring about a third of a mile away. The pipe was of fir logs joined with oak couplings. It had a two inch hole through it and worked for years. Very few homes had such a good water supply.

Naturally, in those days I walked to school, which was a mile from the farm. They were the country schools of Norridgewock. We got along pretty well in the spring and fall, but it was some task in winter. In those days we had four times as much snow as we do now. After a while, we went by team to the school in Norridgewock, but there were two weeks every spring when the roads would be impassable on account of mud. Then we walked on the railroad track for two-and-a-half miles. After my graduation from high school, I went to Business College in Augusta.

Mr. Sam Philbrick, Bill’s (William Philbrick) father, gave me my first job. He was Treasurer of the Kennebec Log Driving Company and had charge of the log drive from Moosehead Lake and Dead River to Augusta. The river was divided into sections each ten miles long. I worked on the Madison sections as Timekeeper and Cookee. In addition to keeping the men’s time, I also had to arrange four meals a day for them: breakfast at 4 a.m., luncheon at 10 a.m., dinner at 2 a.m., and supper at 7 a.m. I didn’t have much social life that summer.

Old timers will remember that in those days, logs were driven in lengths of 15 to 30 feet, and sometimes they piled up in a jam. That year, there was a 15 million foot log jam just above Madison. It took a month to clear it, and that year we ran 125 million felt of logs down the Kennebec.

When the log drive was over, Mr. Philbrick helped me get a job in Charles Ward’s Clothing Store. It was located on Madison Ave. and I was paid $2.50 a week. Later, Mr. Ward took me into the business and I stayed until 1910. The store had a bad fire in 1904.

In 1911, Carl Holt and I went into the potato and hay business. We shipped about 150 carloads of potatoes a year, and a carload would hold from 600 to 1,000 bushels. These were sold by telegraph to brokers in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

We bought hay in the farmer’s barn and pressed it. One winter, we operated 10 presses, each having a crew of seven men and a team. Each press could handle seven to 10 tons a day, making bales of about 200 pounds each.

Mr. Ward had the first automobile that came to town and I had the second. I bought it in 1906 from Roland Patten after he had had it a year. It was a Locomobile with tilt steering and steam driven, and we were as much of a curiosity in those days as would be an atomic powered car today.

In 1911, Hight started doing quite a business selling model T Fords. They were shipped to us knocked down, six in a car. The bodies were lined up on the sides of the freight car, and the other parts were pinned down all over the place. They had no starters, carbon lamps, brass horn with bulb, small tires, and sold for as low as $440 delivered, and that was for a brand new car. Our mechanics put them together.

The roads were so bad that driving was limited to the summer months, from June through October. But we received cars all winter, assembled them, and put them in stables and barns waiting to be sold. They were not hard to sell, even in those days.

The first one I sold, I picked up in Lewiston. I didn’t get out of the city before it stopped. I had to walk back and get them to start it for me. They showed me what I might have to do if it stopped again and when I got to Greene, it did. There was no screwdriver in the kit, but a nice lady sold me one from her sewing machine. Then I took out three little screws under the floor board and cleaned the timer of lint. I did this half a dozen times coming home. To this day, that is all I really ever have learned about the mechanical parts of an automobile.

In 1914, we took the Buick agency along with the Ford. During the war, it was hard to get freight delivery of cars, so we sent men to the factory to drive them home.

At one time, we sent 13 men to the Buick factory at Flint, Michigan. Myron Smith went on that trip and the cars at that time were all open models. What a sight those cars were when they arrived here, mud from end to end, and the tires in bad shape. One driver ruined the motor on the car he was driving and left it in New York. We had trouble with the people who bought those cars.

About every man we had a car sold to swore he would not take such a looking car and I didn’t blame them. They said that they were second hand. We locked the cars into a building, kept the lookers out, put on a crew of men and cleaned and polished them. Finally we delivered them to our customers.

In the war years, Fords were assembled in New York. We sent men there and they would drive one home, towing another. From about 1917 to 1925, we bought our Ford parts in carload lots. After the war, the business began to boom. In 1921, we sold 334 new Fords and 121 new Buicks, besides 151 used cars.

Since my days on the farm, I had always liked horses, and the work of selling automobiles never has changed that. In the fall of 1947, I went to the Lexington Trots, in Kentucky. While there, I bought two colts, a pacer and a trotter. The pacer, I raced for two years and then sold her. The trotter, Cynical Way, gained considerable prominence as a two-year old at Roosevelt Raceway. The next year, as a three-year old, we won a number of races with him. We kept him paid up in the

Hambletonian those two years, and in August, started him in this race for a purse of $60,000. There were 125 colts named in this stake the winter before, but only 21 came out to start the day of the race. Cynical Way landed 6th. Didn’t get much of the money, but was racing with the best colts in the country.

At Lexington that fall, I bought two more colts, both of which went lame. Next year, I bought Brewaway, which some of you have seen. For him and a halter, I paid $5,000. The first time we started him at Goshen, he won a $4,000 stake as a two-year old.

Looking back over my young business career, I remember after I had been in the (Charles Ward’s) store two or three years, in December just before Christmas, I came down with smallpox. I doubt if many of you realize what a contagious disease smallpox used to be. At that time, there were a few cases in town and many more in the county.

When I was first taken, the doctor treated me for what I thought was a bad cold with quite a temperature. I was in my room about a week, seemed better and the doctor let me out on Sunday. I went to the Milburn Club, had dinner at the Oxford Hotel, and called on friends in the afternoon. I went to work in the store Monday morning.

About 10 a.m., the doctor came in, called me to one side, and looked me over. He said, “You had better go up to the farm. I am not sure, but I am afraid that you have smallpox.” I called up my brother Ed and asked him to meet me at the electric car. When I told mother what the doctor had told me, she was wild. She called our family doctor and he pronounced it smallpox.

Next came the Health Officer with a red flag that put me in quarantine for 21 days. If any of you have ever been confined in a room alone for three weeks, you know what I went through. The fever had really left me at the end of the first week and I felt perfectly well, but I could do nothing but stay there. I resolved then and there never to do anything to get into jail and I led a virtuous life.

It wouldn’t have been quite so bad if I hadn’t been working in a clothing store and just before Christmas at that. As soon as it became known I had small pox, they began to fumigate every place I had been on Sunday: the home where I roomed, Milburn Club, Hotel Oxford, and where I had called on Sunday evening. Charles Ward had his store fumigated three times. It cut his Christmas business to almost a cipher.

After the quarantine period of 21 days was up, the Health Officer came and gave me a bath in formaldehyde. I didn’t mind the bath so much, but the fumes killed every plant in mother’s house. I then came back to Skowhegan and as soon as Dr. Stinchfield found I was in town, he ordered me to his office and gave me another formaldehyde bath!

During the war period, we were on high tension as to just what we could sell legally, as there were stamps and ceilings, regulations of all kinds. A man from Greenville that owed us on a car came in and said he did not have the money, but would have to give his note. So I made out the note and he signed it. As he went out of the office, he said to me, “I want five gallons of gas, is that stamp all right?” I told him I did not know, but would ask the clerk. He said he thought it was all OK, so he put in five gallons of gas and the man paid. Then he came to me and said, “You are under arrest,” and showed his badge. “You are selling gas illegally,” he said. “That stamp is not good.”

As you can imagine, I was quite excited. The next thing I did was go out into the garage and walk the floor thinking what to do. As it was about 12 o’clock, I thought I would go to lunch and leave him in the office. Over at Gene’s, I found Bill Philbrick and Lawyer Weeks from Waterville sitting at a table, so I sat down with them and said, “I am in trouble, can’t you help me out?”

I told them my story and we discussed it pro and con. Weeks said if I could get the gas out of his tank, give him his stamp and money back, he would not have any evidence against me. So, I went back to the garage, told the men the story and we organized. When the man found I had left him, he told the boys he would be right back.

When he came into the yard, I took the gas cap off his car, one of the men reached in and took the keys out of his switch, another put a piece of hose in his gas tank and siphoned out the gas. We gave him his money and stamp back and he left, as he said, for the jail to have us all arrested, but I never saw him afterwards and he never paid the note!