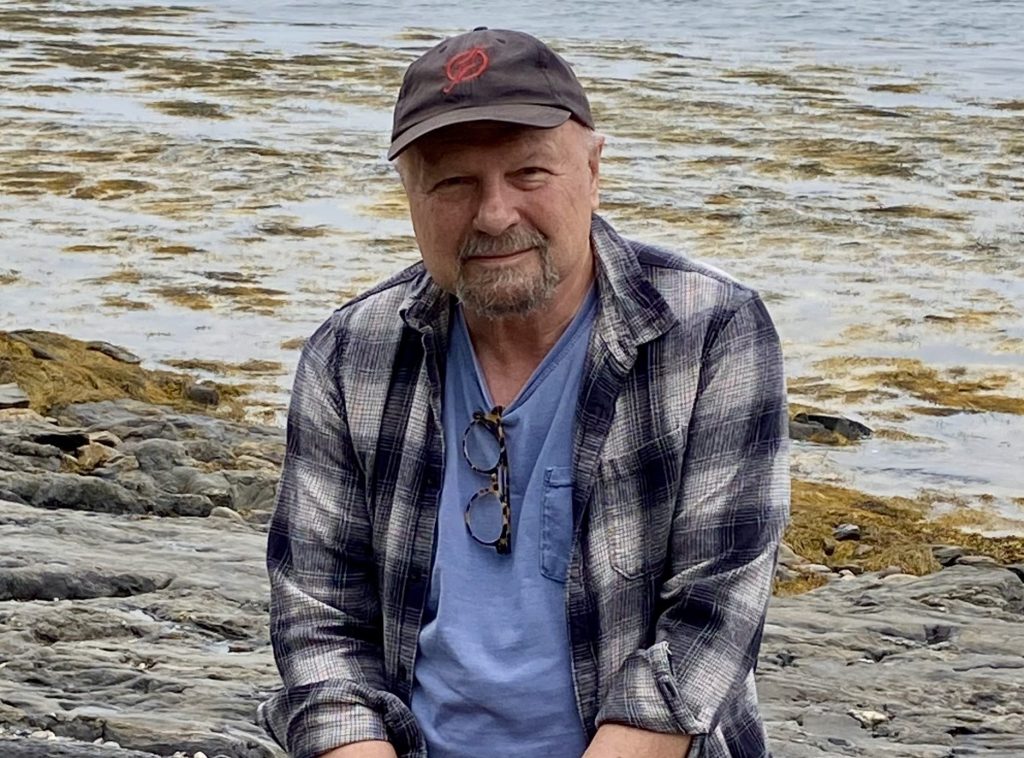

Bau Graves had a boundless optimism, especially when it came to music.

Whether it was putting together a touring band with more than 30 mandolin players, bringing Mongolian throat singers to Maine audiences, or recruiting performers for some of the state’s biggest annual cultural events, Graves never doubted everything would be all right.

“He always felt everything was going to work out fine, and I think that optimism and his creativity made him really good at what he did,” said Joel Eckhaus, of South Portland, a string instrument maker and bandmate of Graves. “He knew good music, he was incredibly creative and he was willing to try anything.”

James “Bau” Graves, who died Sept. 24 at home in Harpswell at the age of 73, used his can-do spirit and deep passion to impact and expand Maine’s music and cultural scene, from the 1980s into the mid-2000s.

He was artistic director of the Maine Festival, which was the state’s showcase summer arts and music event for decades. With his wife, Phyllis O’Neill, he started the beloved New Year’s Portland celebration in the early 1980s, where dozens of musicians performed each year at venues all over downtown. The event ran into the early 2000s.

Also with O’Neill, he created a performance series called Big Sounds From All Over, bringing music from around the world to Maine. The couple continued that mission from the late 1990s to the mid-2000s by running a Portland venue called the Center for Cultural Exchange in the music and performance space One Longfellow Square occupies today.

O’Neill said her husband’s passion for a wide variety of music and different cultures was a constant in his life, not something he pushed to one side when not working.

“It was his life. He didn’t really separate the work from who he was,” said O’Neill. “If you came to our house, you’d find instruments all over the place and music all over the place. There was a creative place inside him, where he could see the way things could come together.”

Graves and O’Neill moved around 2008 to Chicago, where Graves was executive director of the Old Town School of Folk Music. He held a master’s degree in ethnomusicology from Tufts University in Massachusetts. He and O’Neill returned to Maine about seven years ago, and Graves continued to write, play music and raise money for causes he believed in. He worked recently as development officer for the Greater Portland Immigrant Welcome Center.

As a musician, he played guitar, button accordion and mandolin, among other instruments. In a duo with Eckhaus called the Neverly Brothers, they played about six or seven instruments between them. He also was involved in a group called The Howitzers that eventually included more than 30 mandolins playing together. Sometimes tap dancers joined the group.

Jim Pinfold, a longtime music store manager and buyer who worked at the Maine Festival, remembered that even when Graves was really focused, deep into the minute details of a giant music event, he would get positively giddy once the performers began playing.

“I remember him being frazzled, moving really quickly across the Bowdoin campus (where the Maine Festival was first held). But then when any of the artists took the stage, he was just thrilled,” said Pinfold, of South Portland. “All of it was exciting to him, every performance. That is so rare for someone who does that sort of job.”

The Maine Festival was founded in the mid-1970s by Maine humorist Marshall Dodge, known for the “Bert and I” humor records, and for years it focused on Maine performers and artists. After Graves became artistic director in 1987, he and O’Neill expanded the lineups to include performers from all over the country and the world. O’Neill served as director of the Maine Festival at the time.

Besides bringing world music to Maine, Graves also brought accomplished pop music stars like Ray Charles and Tony Bennett and all sorts of blues, folk and jazz artists to play at festivals, events and venues.

Raised outside Detroit, Graves had come to Maine in 1976 and opened Welcome Home Music in Brunswick, according to an obituary written by his family. His store sold instruments but was also a gathering place for professional and aspiring musicians. From there he started presenting small concerts and playing in and organizing bands.

Pinfold said the performers Graves and O’Neill brought to Maine at festivals or other venues helped expand his musical taste, and probably did the same for lots of other people.

“I was sort of a music snob. I was a jazz guy. But then I started to see the people they (Graves and O’Neill) were bringing in and it knocked my socks off,” Pinfold said. “Nobody else was bringing in the kind of performers he was then. To have this fire hose of Cajun music and Zydeco and African bands and fiddlers and Scandinavian ensembles and throat singers was very exciting.”

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can update your screen name on the member's center.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.