PORTLAND — In the hours and days after Maine’s deadliest mass shooting, Michelle Ames recalled watching press conferences and media coverage with frustration.

“There was no (American Sign Language) interpreter visible on screen,” she signed. “I was extremely upset. I couldn’t even focus on what was happening.”

A man had started shooting in Schemengees Bar & Grille in Lewiston, where a group of deaf and hard-of-hearing friends had gathered for a cornhole tournament. Four of the 18 people killed on Oct. 25, 2023, were deaf.

But Ames had to jump into action. She joined those gathered at the Armory in Lewiston to support survivors. She attended the first meeting at what is now the Maine Resiliency Center.

“I had the feeling that I needed to be strong, that I needed to mask some of those feelings I was having because of the position that I have as co-director of deaf services at Disability Rights Maine,” Ames said. “I needed to be there for the community.”

Right now, the University of New England Art Gallery in Portland is showing an exhibition of work by deaf artists and craftspeople, paired with color photographs of Lewiston by the artist Michael Kolster. The exhibit celebrates Maine’s Deaf community, recognizes the work of ASL interpreters and offers a place for healing, two years after the shooting.

Ames curated the exhibit with Meryl Troop, a longtime colleague and ASL interpreter. An artist herself, Ames also made a piece for the show. “Unwrapping” is a mixed media work with layers of paste paper, burlap, newspaper clippings from the shooting, fabric and other materials.

“It was an opportunity for me to take a moment, to take a step back and look inside of myself, all of these different layers I’ve built in myself over the past few years as a way of healing for myself as well,” Ames said.

‘A DEEPER WORLD’

Hilary Irons is the gallery and exhibitions director at the university’s art galleries in Biddeford and Portland. She has studied art history and worked in her field for years, but she had never learned about De’VIA, or Deaf View/Image Art.

“I had never encountered this term,” Irons said. ” I felt like there was a big gap in my learning.”

A group of deaf artists defined the term in 1989. Not every deaf artist makes work in this realm, and their work is not considered De’VIA by default. De’VIA specifically expresses the Deaf experience. The work might be characterized by high contrast in colors or values, intense colors and contrasting textures. It might also emphasize hands and facial features, especially eyes, mouths and ears. Certain symbols, such as butterflies and dandelions, might repeat.

One artist in the gallery is Nancy Rourke, an artist, activist and enrolled member of the Mesa Grande Band of Mission Indians. She has exhibited her work around the world, and her painting in this show is called “Reclaiming Cornhole (ala Guernica).” On her website, Rourke said she always works in the primary colors and assigns specific meanings to each one. Yellow, for example, symbolizes hope for the future and also the light needed by deaf people to access information.

“My paintings show both the truth of how we are oppressed and how our community celebrates our collective identity and culture,” Rourke wrote on her website.

Irons said she hopes the exhibit will celebrate De’VIA for those who know it and introduce it to those who don’t.

“It’s another way for viewers who may not have intersection with this community to recognize that there’s a deeper world of experience to learn about and to recognize and celebrate,” Irons said.

ASL AT THE FOREFRONT

The curators wanted to make sure that the Deaf community could fully engage with the exhibit. The walls are dotted with QR codes that link to videos of the artists or interpreters signing about the artworks.

In one video, Troop describes the piece she contributed to the exhibit. She made a mixed fiber work called “Cascade of Dandelions,” inspired by deaf poet Clayton Valli’s “Dandelions.” In the poem, the flowers represent the Deaf community’s tenacity in the face of being “mowed down.” Visitors can also watch a video of the poem on the second floor of the gallery.

“It’s an opportunity for deaf people to interact directly with the information, rather than going through the medium of what may be a poor second language,” Troop said.

Troop and Ames were thinking about the particular audience at the University of New England when they curated the show. Many students there will go on to work in health professions. Troop said she was on call for medical and legal emergencies through a statewide network of ASL interpreters on the night of the shooting but was never contacted.

“My goal in approaching UNE was to impact future medical providers because of the failures of the medical system and the police department to provide timely, in-person Sign Language interpreting at such a devastating time within the community,” Troop said.

PICKING UP THE PIECES

Many artists responded specifically to the tragedy that occurred in Lewiston nearly two years ago.

Miia Zellner, who lives in the town of Mexico, shared a work for the exhibit called “We Rise.” She made the piece for a vigil in Lewiston just days after the shooting, and in the painting, a hot air balloon containing the names of the 18 victims rises above a shining sun.

Toby R. Silver, who lives in Maryland, stitched the outline of the state for a piece called “Maine Mended.”

Roxane Baker, who teaches at the University of Southern Maine, created a cornhole game that can be played in the gallery. The bags are dyed in blue and yellow, the colors of the Maine Educational Center for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, which was formerly known as the Governor Baxter School for the Deaf.

The show also includes another artist — Michael Kolster, who teaches at Bowdoin College. Irons chose to include large color photographs Kolster recently made in the city. In these images, Lewiston is vibrant with art.

“He has the ability to bring to life some of the aspects of the city that he finds to be moving and beautiful and contemplative,” Irons said.

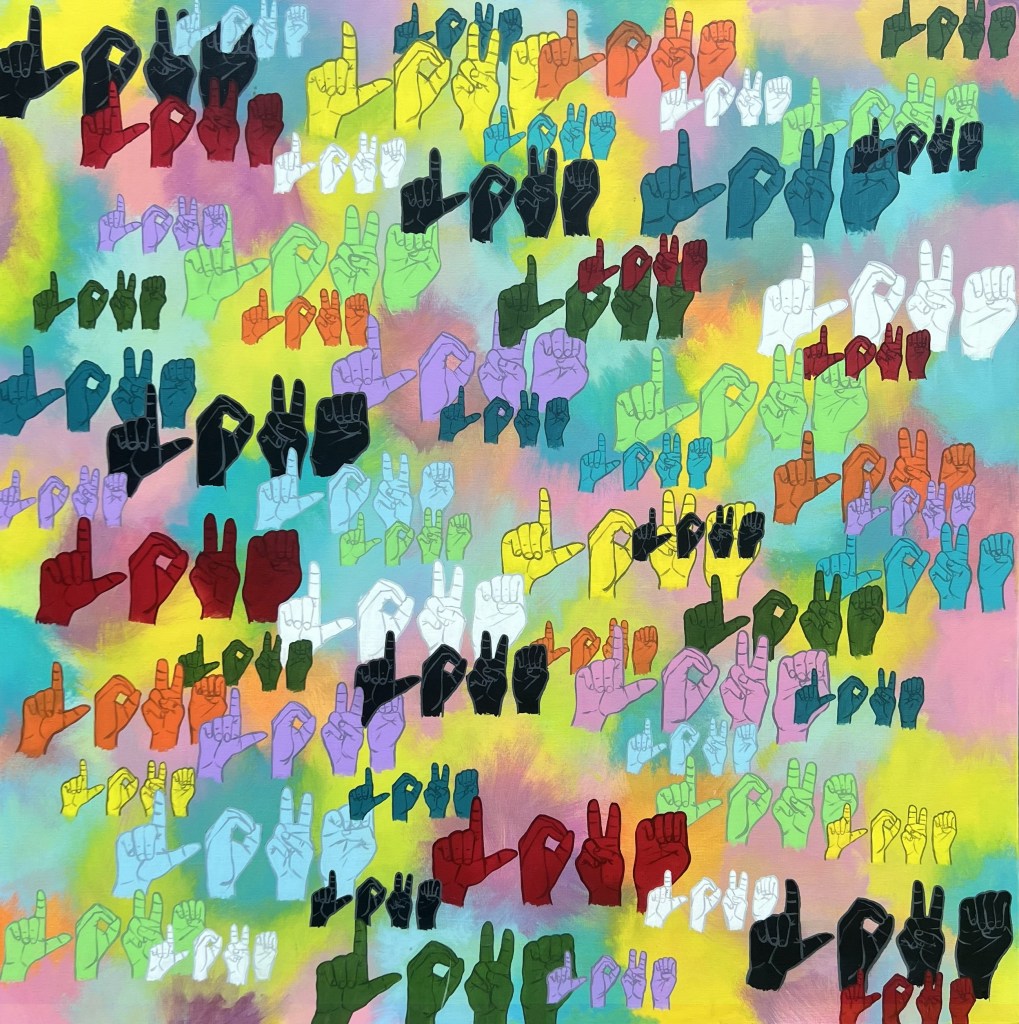

Last year, guests at Maine’s annual Deaf Culture Festival spent time painting individual squares of canvas. Some referenced the shooting as they made their designs. One says, “Healing Together.” Another says, “Lewiston Strong.” Others painted trees and rainbows and butterflies and hearts.

“It was unpredictable how it would turn out,” Ames said. “And it came out really beautifully.”

Now, the squares are sewn together. They greet visitors to the gallery with a sign in ASL: “I love you.”

IF YOU GO

WHAT: “Unspoken Resilience: Healing from the Lewiston Shooting Two Years In”

WHERE: University of New England Art Gallery, 716 Stevens Ave., Portland

WHEN: Through Feb. 7

HOURS: Open Thursday through Sunday 12 p.m. to 5 p.m. Closed Monday through Wednesday.

HOW MUCH: Free

INFO: For more information, visit library.une.edu/art-galleries/