Decades after surviving the Holocaust, Charles Rotmil often shared a simple but powerful message: “I don’t live in the past. The past lives in me.”

Rotmil, one of Maine’s most significant voices in Holocaust remembrance and human rights education, died Tuesday morning, his partner, Cathryn Wilson, confirmed. He was 93.

After emigrating to the United States and settling in Maine, Rotmil shared his story with thousands of students and pushed for schools to teach about the genocide committed against Jews by the Nazis in German-occupied Europe during World War II.

“We need to know what happened during this period so that it will never happen again,” Rotmil said during testimony before the Legislature in 2021.

Rotmil, of Portland, was remembered Wednesday as a storyteller, survivor, artist and teacher whose openness about his horrific experiences as a child impacted the lives of many Mainers.

“Through his stories, his art and his courage, he inspired countless students, educators and community members to stand against injustice and embrace compassion,” Tam Huynh, executive director of the Holocaust and Human Rights Center of Maine, said in a statement. “His presence will be deeply missed, and his legacy will live on in every student he taught and every life he touched.”

Secretary of State Shenna Bellows came to know Rotmil well while she was the director of the HHRC and said it was inspiring to see his courage, authenticity and resilience in action.

“It must have been difficult and painful for Charles to tell the stories of the Holocaust and his personal losses over and over again, but he recognized how important it was,” Bellows said. “He had seen the worst of the worst. He lost his parents, he lost everything, yet he survived to share the lessons of the Holocaust with the next generation.”

SURVIVING THE HOLOCAUST

Rotmil was born in Strasbourg, France, in 1932, six months before Adolf Hitler came to power. He would later tell people his childhood was normal until his family moved to Vienna.

After Nazis closed the synagogues, religion centered around the dinner table for Rotmil and his family, he told students during a 1994 school visit in Waterboro.

“To this day, I like to linger at the table,” he said.

During Kristallnacht — two nights of violent persecution of Jewish people across Germany and Austria in November 1938 — German soldiers smashed down the family’s door and arrested Rotmil’s father after beating his head against a table.

The next morning, Rotmil and his sister walked over shards of glass and past walls scrawled with antisemitic graffiti. The family fled to Belgium, where Jewish refugees were being accepted. Rotmil’s father carried him through the woods during their journey.

When Belgium was invaded in 1940, thousands of Jews were forced to walk into France while airplanes shot at them from above. The scene was “total chaos,” with fires burning on the horizon and dead bodies strewn across the road, Rotmil recounted decades later.

Rotmil’s father, Adi, left the road to find a wheelbarrow for their bags and disappeared, but the family continued on and boarded a train. His sister died when the train hit a car on the tracks, and his mother died a week later from her injuries.

Rotmil and his brother, Bernard, were eventually reunited with their father and went back to Austria. There, their father was turned in by a neighbor and arrested. He was executed upon arrival at the Auschwitz concentration camp.

With help from Father Bruno Reynders, a Belgian monk who hid over 350 children, Rotmil and his brother were sheltered in Christian homes. They often had to change their names and lived in constant danger, according to the HHRC.

On a foggy morning in December 1946, Rotmil and his brother arrived in the United States aboard the Ile de France and went to Peekskill, New York, to stay with their aunt and uncle.

A CREATIVE LIFE

After college, Rotmil worked as an assistant to a prominent photographer in New York City, where he was active in the downtown arts scene in the 1970s. He photographed artists Andy Warhol and Robert Indiana, said Wilson, Rotmil’s partner. His photographs of artist Bob Thompson were included in a retrospective at Colby College a few years ago.

Rotmil was also a painter and filmmaker. His short film “The Eternal Hat” was featured in the 1970s in the Ann Arbor Film Festival. Another short film, “Street Musicians,” won an award from Space Gallery in 2007, Wilson said.

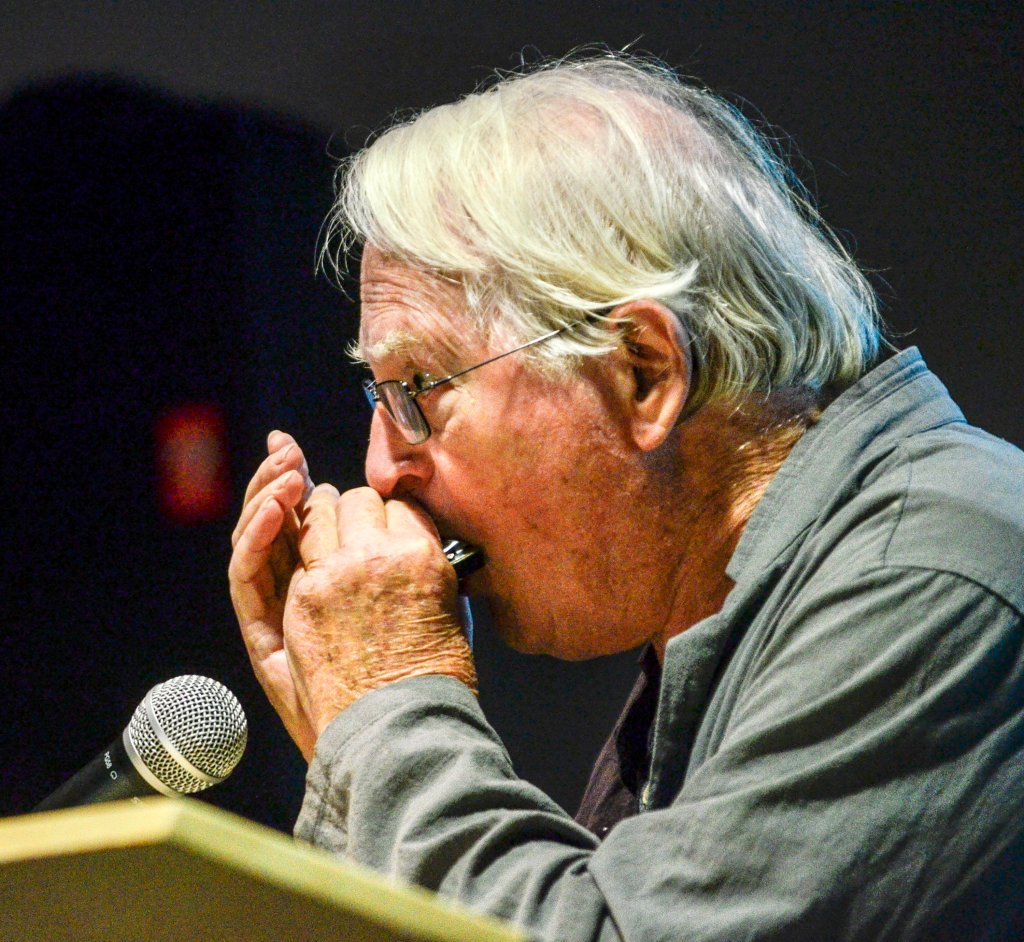

He played a variety of instruments, including guitar and Japanese flute. He often brought his harmonica to schools to play for students during his presentations. He enjoyed writing both fiction and nonfiction, and was working on a manuscript about his life before his death.

“He was a very gifted artist on many different levels,” Wilson said. “He was a very alive, creative person with a great sense of humor. People would be caught by surprise.”

Rotmil, who had four children, moved to Maine in 1982 and started a career teaching foreign languages to high school students. Wilson said he was somewhat of a teaching nomad, working at schools across the state — from the western mountains to the Midcoast to Aroostook County.

Wilson said Rotmil, like many Holocaust survivors, didn’t always speak openly about his experience in the decades after he came to the U.S. But by the 1980s, more people were interested in hearing from survivors about their experiences, she said.

“He was aware that hatred still exists. He thought there were very important lessons to be learned about what happened during the Holocaust so it wouldn’t happen again. He sensed a responsibility to share what had happened,” Wilson said.

Bellows said Rotmil was a charismatic and compelling speaker. When he was talking to students, it was sometimes the first time students were learning about the Holocaust. It was clear some students felt shock, anger and sadness, but he also “brought some light and hope for the future to his stories,” she said.

“He was always able to communicate the importance of human rights and standing up to evil,” Wilson said.