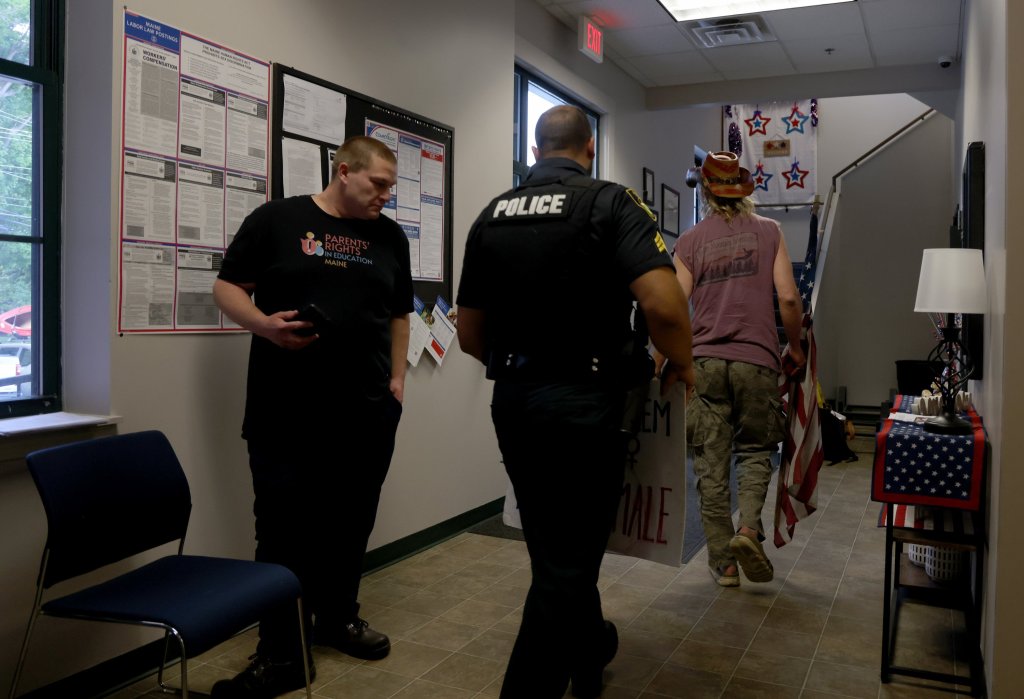

“We’re going to recess if this doesn’t stop,” Superintendent Patricia Hopkins says.

The man in the American flag cowboy hat continues to shout.

“You’re wrong, all of you!” he yells as a police officer leads him away. “Screw you all!”

At the front of the room, a school board member sits with her face in her hands. Another has joined in on the yelling.

Most wait in frustrated silence. It’s been a long year in Gardiner, Maine.

And it’s going to be another long night.

Maine School Administrative District 11 board meetings used to be sleepy affairs. At the June 5 meeting, some of the teachers, parents and community members that looked on were horrified, but most sat unfazed by the now-routine chaos.

School boards have become one of the nation’s fiercest political and cultural battlegrounds. That’s no accident.

Parental rights organizations, which experts estimate number in the hundreds, are at the heart of the movement. They want parents to have more say over what is being taught in the classroom and when — often pushing conservative values.

Leaders of these groups say they are simply advocating for their beliefs, just like those who support LGBTQ+ rights and other progressive ideas in schools. The strategy is deliberate: create delays and disrupt public meetings as a way to make their views known.

Last year, as MSAD 11 officials considered accepting grant money to open a general health clinic at the high school, parents’ rights groups spread false information that it would provide puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to trans students. The proposal soon became a flashpoint for both locals and out-of-state conservative activists. Some took to harassing school board members and anyone else who supported the clinic.

A loose network of organizations and individuals associated with the parents’ rights movement have recently made headlines across Maine. In nearby Augusta, police arrested a man at a school board meeting in January for refusing to give up the floor after using his allotted time for public comment, although he was never charged. After that, a local conservative activist placed a communist China flag on the chairperson’s desk.

Then last month some meeting attendees stripped down to their underwear to protest the Augusta district’s transgender sports policy.

A six-month Kennebec Journal/Centralmaine.com investigation found that this pattern is part of a larger, widespread effort to remake public education by funneling millions of dollars from prominent Republican donors to conservative influencers, activists and local politicians in towns around the country.

After conducting dozens of interviews, viewing hundreds of hours of school board testimony and sorting through thousands of pages of records, we found:

- National groups have aided a coordinated effort to stack Maine school boards with conservative candidates who support religious learning and oppose pro-LGBTQ+ and diversity policies. Some of these groups are linked to major conservative donors and policymakers, including the architects of Project 2025 and others who openly espouse Christian Nationalist views.

- Because Maine law does not require financial disclosures in most school board elections, it’s impossible to trace exactly how much money is flowing directly to these candidates and from where. But experts say even small amounts can have major impacts in these races.

- An active network of conservative outlets, social media groups and influencers draw outsized attention to hot-button issues like diversity and transgender rights, encouraging local resistance and amplifying the fights until they reach the national level.

- Once conservative candidates win seats on school boards, they are instructed to intentionally stir up chaos and disrupt the district’s work in order to call attention to their chosen issues. Community members who oppose their agenda may face online harassment.

Experts say this is a part of a nationwide effort to undermine trust in the public education system and that a clear link exists between Christian nationalism and parents’ rights organizations.

While some organizations have openly stated they are Christian nationalist, espousing the idea that the United States was founded as a Christian nation and should continue to be one, others are tied through donations made by known Christian nationalist organizations or individuals.

In Oklahoma public schools, the state’s former superintendent of public instruction has required the Ten Commandments and the Bible be incorporated in their school lessons.

However, it can start with book banning and anti-transgender policy, as Mainers have seen at fiery school board meetings across the state.

“If you attack the public schools, disrupt the board meetings and cause chaos and badmouth the district and teachers, low-information parents, or parents working multiple jobs start to fear what is going on in schools,” said Scott Hottenstein, who has helped run several school board campaigns in Florida against parents’ rights candidates.

In Gardiner, a small city in central Maine that makes up the largest share of MSAD 11, what was supposed to be a simple vote to open a health clinic at the high school drew the ire of conservatives across the state and country and pulled the district into an ugly fight spanning an entire school year.

THE PARENTS MOVEMENT

HealthReach, a local nonprofit, wanted to open a school health center in Gardiner. To some, it seemed like a no-brainer.

About 40% of high schoolers in the district are “economically disadvantaged,” according to U.S. News and World Report. Many have limited access to health care or insurance.

Supporters said the new clinic, funded entirely through grants, would make it far easier for students to get checkups and basic care.

Others saw a more sinister force at work.

In October 2024 during the district’s preliminary meetings on the proposal, Michelle Tucker wanted to know whether the health center would keep secrets from parents about transgender treatments for students.

Tucker moved to town in April; her daughter was not enrolled in the district. (She had previously pulled her daughter out of another public school.) Her actions reflected a core tenet of the growing parents’ rights movement: the public education system has quietly been indoctrinating students with liberal ideology while shutting out conservative voices.

Parental rights organizations gained momentum during the COVID-19 pandemic by focusing on mask and vaccine policies in schools. As the issue became political, school board meetings became fertile ground for conflict.

“Around COVID was when I think they really saw an opportunity,” said Ryan Jayne, an attorney from the Freedom from Religion Foundation, a nonprofit that aims to maintain the separation of religion from public entities. “People were angry at school boards for how they handled COVID and remote learning and saw a big opportunity for them to swoop in and say we need to install people on the board who are going to run the things the way we want.”

Perhaps the largest such group in the United States is Moms for Liberty, which reports having over 300 chapters nationwide, including several in Maine. The group calls itself a right-wing organization and has gained the support of President Donald Trump and his allies.

“The path to save the nation is very simple: It’s going through the school boards,” Steve Bannon, Trump’s former chief strategist said on his podcast when he interviewed the Moms for Liberty founders in 2021 as reported by The Nation.

So that’s the path conservatives followed.

As the movement has grown, parents’ rights organizations have leveraged other culture war issues in schools, like the display of pride flags, LGBTQ+ representation in children’s books and trans bathroom policies.

To them, the proposed health center in Gardiner was a Trojan horse — one more way for liberal educators to insert themselves into children’s lives without involving parents.

Tucker and other opponents warned the clinic would provide antidepressants, birth control and gender-affirming care, including hormone treatments, behind parents’ backs.

And to her, it felt personal. When a state law passed in 2021 removed the religious exemptions for vaccine mandates in public schools, her daughter was still in high school. Tucker joined a parents’ rights group on Facebook and found a community. She said she didn’t understand how anyone could make medical decisions for her and her daughter.

So it mattered little that officials from HealthReach said the Gardiner clinic would not provide hormone treatments for gender-affirming care.

After Tucker announced a run for school board that November, parents’ rights groups rushed to promote her candidacy.

The Maine First Project, a Brewer-based nonprofit led by former state Rep. Larry Lockman, sent out a batch of flyers supporting her campaign and asking residents if they wanted to “Make Maine schools Safe again.”

Tucker denied working with the group and said she didn’t know about the flyers until after she got one in the mail herself, but said she endorses its message. Nearly identical flyers also promoted school board members Barry Manning and Sean Focht (who is no longer on the board). Tucker said Focht encouraged her to run for the position.

Tucker was elected by a 100-vote margin, beating out three other candidates, two of whom had experience serving on the school board and another who had attended Gardiner Area High School and worked for most of his life at the city’s Boys & Girls Clubs.

Having graduated from attendee to board member, Tucker was now well-positioned to stall progress on the health center. She spent months making it the focus of nearly every school board meeting she attended.

As opposition built, the district had to spend nearly $150,000 on an attorney to respond to the wave of public records requests about the proposal and on a police officer to provide security at meetings. School board members started to face protracted online harassment for supporting what many saw as a straightforward solution for the community.

Tucker was perhaps the most visible leader of the opposition, but she was not alone. Public records show that throughout the debate, conservative members of the board coordinated closely with Allen Sarvinas, an activist who sits at the heart of Maine’s parents’ rights movement.

FOLLOW THE MONEY

Sarvinas said he is not paid for the work he does to support parents in places like Gardiner, about 24 miles from his hometown of Topsham.

As director of the Maine chapter of Parents’ Rights in Education, the state’s most prominent parents’ rights group, he said he usually gets involved after a parent contacts him with concerns about transgender girls playing on girls sports teams, literacy levels, test scores or teachers sharing their political views.

That’s when Sarvinas will begin to show up to board meetings, lobby school administrators and coordinate strategies with allies on the board — all on his own dime.

But it’s not quite that simple.

Sarvinas is just one part of a complicated ecosystem that connects billionaire conservative donors to politicians and local activists.

Many parental rights groups in Maine have links to powerful national organizations. Most, if not all of them, use the same messaging and are tied to one another through training, monetary donations and members.

How these groups made their way to Maine is murky, but at least two far-right megadonors have connections to the state: Thomas Klingenstein, a hedge fund manager and head of The Claremont Institute, grew up in Portland and has a home in Belgrade; and Leonard Leo, a conservative legal activist and co-chairman of The Federalist Society, has had a house on Mount Desert Island for years.

It’s easy to get lost in their overlapping string of donations, but Klingenstein’s money has a pretty clear line to MSAD 11.

He donated $10 million to right-leaning organizations in the 2024 election cycle, according to reporting from The Guardian. Some of that fortune went to Alvin Lui, a former magician turned political pundit who runs a group called Courage is a Habit.

In 2023, Lui’s group raised just over $200,000 — $175,000 of which was donated by Klingenstein — recent tax records show. Nearly all of it went to Lui’s salary.

It’s unclear why Klingenstein supports Courage is a Habit. Although his political donations have ramped up in recent years, public records indicate he is selective about which groups he supports. Klingenstein did not respond to multiple requests for comment about his donations, nor did Lui when asked about the funding.

Lui, who lives in Indiana, has more than 38,000 followers on X. After learning about the health center controversy, he was quick to unleash them on Maine, a state he said he first set foot in earlier this year.

In June, Lui broadcasted himself watching the livestream of the MSAD 11 board meeting. About 1,000 people joined.

“We’re here to stream the transgender cultists’ school board MSAD 11 to see how they’re voting for the health clinic,” said Lui, wearing a hat that read “Embrace Exclusion.”

Seven months earlier, he had become transfixed by Gardiner’s proposed school health clinic and started regularly posting about it on social media.

“This is a school board in Maine, but ANY American across the country can help stop them. It’ll take 30 seconds,” Lui wrote to his followers, urging them to message MSAD 11 leaders about the health clinic. By June, Lui said they had sent 13,000 emails, according to a video he posted on Facebook.

Lui has appeared on several conservative Maine influencer’s podcasts, including Muddy Waters, hosted by Chuck Ellis, and The Robinson Report, hosted by Steve Robinson, editor-in-chief of The Maine Wire. Tucker, too, appeared on Muddy Waters and on Lui’s show.

Sarvinas has connections to Klingenstein, too. Although he said he does not take a salary from Parents Rights in Education, Sarvinas spends his days working as the outreach director for Maine Civic Action, a nonprofit wing of a conservative think tank called The Maine Policy Institute, which received nearly $600,000 from Klingenstein between 2021 and 2023.

The Maine Policy Institute also runs and funds the far-right news outlet The Maine Wire, which often writes about these issues in highly charged language and amplifies the message of activists like Lui and Sarvinas. The group also started The Maine Education Initiative, a similar organization to Parents Rights in Education, run by former Maine state Rep. Heidi Sampson. Sarvinas is an adviser to the organization. It was recently featured in an article on Klingenstein’s website.

Leo, through his role as the co-chairman of The Federalist Society, played a major part in shaping the current ideological makeup of the U.S. Supreme Court. He’s also donated $50,000 to For Our Future, another political nonprofit that is run by Alex Titcomb, who is head of The Dinner Table political action committee that has given money to school board candidates in Maine.

SMALL INVESTMENTS, BIG RESULTS

School board candidates in Maine are required to file campaign finance reports in municipalities with populations larger than 15,000 people.

Only 15 cities meet that criteria, according to 2024 U.S. Census data. That leaves around 250 Maine school boards with no record of the source of campaign funds, including MSAD 11.

Once the money is funneled into local groups, it’s often difficult to track where it goes next.

Tucker didn’t have to file any campaign finance reports when she ran for the MSAD 11 board, but several public transactions are linked to her account on Venmo, an app for transferring money. A user can choose to make those payments private, but several sent to Tucker’s account from “PRE Maine” and Sarvinas’ personal account are public, although the amount is hidden. Tucker said the payment was for “envelope stuffing” for a campaign letter that she sent out.

The app shows Sarvinas also paid several other known school board members tied to Parents Rights in Education through his personal account.

A little money can go a long way in these races.

Gardiner residents received text messages from Parents Rights in Education about the “dangers” of the health clinic. Many reported that they never signed up for blasts, but their contact information can easily be obtained through public voter registration records, said Hottenstein, the campaign manager in Florida who helps organize left-leaning school board races.

Those texting efforts often don’t cost much because of the size of the town, Hottenstein said.

In smaller races, any amount of money can really elevate the name recognition and infrastructure of a particular candidate, said Maurice Cunningham, a former political science professor at The University of Massachusetts at Boston.

Cunningham, who now lives in Damariscotta, has followed parents’ rights organizations for over a decade and traces their donations.

“These races have become much more high profile, much more expensive, more high stakes. School boards usually are kind of those meetings where setting a budget is sort of kind of dry business. Well, now these places have become as explosive as they get,” Cunningham said.

What used to be the type of race where a few donations from family could end in a win, he said, has now become a highly complicated, calculated effort that teeters the line of not being so overly chaotic that their agenda can’t pass.

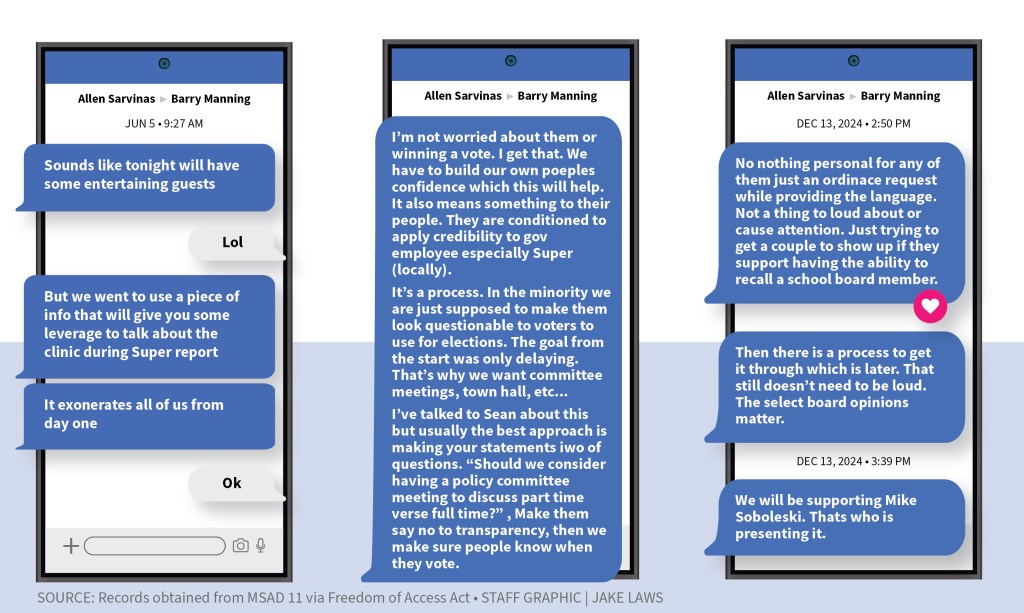

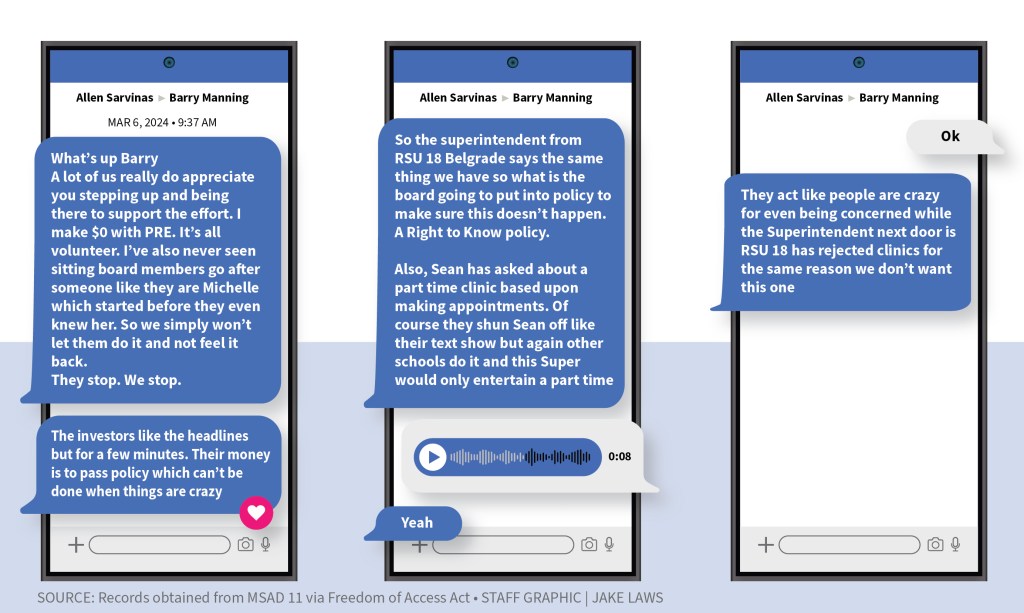

“The investors like the headlines for a few minutes,” Sarvinas said in a Facebook message to a school board member, but, “their money is used to pass policy, which can’t be done when things are crazy.”

COORDINATED STRATEGY

On June 5, Manning raised his hand at the very end of the MSAD 11 board meeting.

“Could we have a discussion about that, a part-time school based health center?”

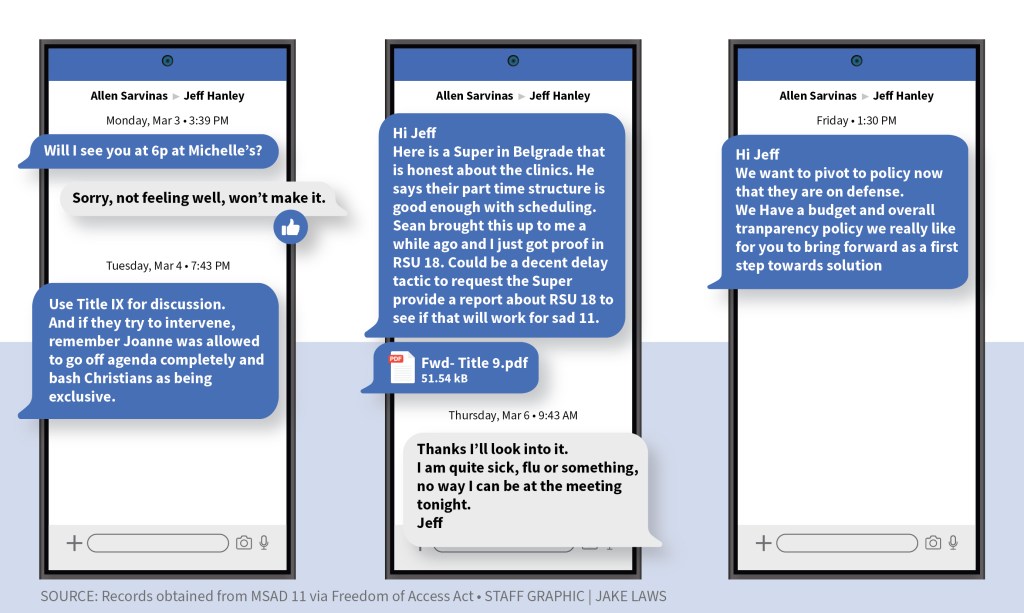

By that point, after early mayhem led to a three-hour meeting, other board members were ready to move on. They weren’t aware that the question was part of a strategy Sarvinas outlined to Manning through Facebook messages, according to copies obtained through thousands of pages of records.

The documents show they talked often about the clinic vote and how Manning and others could stall it.

“It’s a process,” said Sarvinas in one message to Manning on June 5. “In the minority, we are just supposed to make them look questionable to voters to use for elections.”

“The goal from the start was only delaying (the vote),” he said.

Aided by Sarvinas, the conservative block found ways to make that happen.

In December, Tucker had asked if the superintendent of HealthReach, the nonprofit proposing to run the clinic, could provide a memorandum of understanding with the district.

Clinic officials said that’s not part of the usual approval process, but Tucker insisted on having it, creating a blockade that led to a seven-month standoff.

During that time, the clinic’s opponents made life difficult for students, parents and board members who supported the plan.

Freedom of Access Act requests and form emails flooded the district. Public comment periods at school board meetings devolved into shouting matches between protestors like Timothy Bodnar — the man in the star-spangled cowboy hat who goes by the name Truth Slinger on social media — and liberal counterprotesters.

Home addresses of people in the community who spoke out in support of the health clinic were posted online.

Lui, the activist from Indiana, helped pull board members who supported the clinic into the national spotlight; in February, the prominent conservative social media account Libs of TikTok, which has more than 4 million followers on X, posted a photo of school board member Joanne O’Brien along with a screenshot of a Facebook post she made in 2023 before she was elected to the board in which she called for “MAGA’s loud obnoxious parents” to be “forcibly shut down.”

The Libs of TikTok post, which read, “This person is in charge of your children’s education,” was viewed more than 380,000 times.

Three people, including O’Brien, filed for protection from harassment orders against Lui in an attempt to stop his repeated social media posts. Judges rejected all three.

“It’s got to be one of the first cases in Maine where an elected official attempted to silence a citizen,” Lui said later. He did not say why he has involved himself with Maine politics.

Sage Sculli, one of two student representatives on the school board, said in April she learned members of parental rights organizations reached out to her prospective colleges seeking her admission materials. It’s unclear what they were after, but school protection laws prohibited them from receiving anything.

At the same time, Lui posted Sculli’s mother’s work email and phone number online. Jen Sculli said he sent her employer a threatening email over her support of the health clinic.

In June, police escorted two people out of the crowded meeting room because of their disruptive behavior. One of them was Bodnar, who refused to stop hovering directly behind others while holding signs bearing slogans like “No more trans kids.”

Community members shouted over each other as the board finally inched toward a vote.

When it started to look like the clinic would be approved, Sarvinas texted his allies on the school board, including Jeff Hanley, and asked them to start talking about specifics.

“We want to pivot to policy now that they are on the defense. We have a budget and overall transparency policy that we really like for you to bring forward as a step towards a solution,” Sarvinas wrote to Hanley in June.

Hanley did not bring up the health clinic, but did ask the board chairperson to discuss the Title IX policy. The board voted against bringing it up.

After spending nearly an hour discussing the project in executive session on June 12, the board narrowly approved the clinic, six months after the chaos started. The vote was 6-5, with one abstention.

“Don’t worry,” Tucker said when it passed. “We’ll be moving to rescind it in another month.”

THE BIGGER FIGHT

In the last few months, two more candidates with ties to parental rights organizations won seats on the 12-member MSAD 11 board. That brings the total to five.

In other districts across the state, more and more board members have joined Parents Rights in Education. The movement’s messaging has spilled over into other elections, including the upcoming gubernatorial race.

Manning denies that Sarvinas feeds him information to bring up at meetings, but said Sarvinas makes him aware of certain topics and helps him strategize on occasion.

“I feel like you are attempting to paint me as a puppet of Mr. Sarvinas,” he said in response to a reporter’s questions last week. “I assure you, I am no person or organization’s puppet.”

He said he has attended one meeting for Parents Rights in Education but denies being a member of the organization. He said he might join in the future.

Tucker, who recently took over as Maine chairwoman for a parents’ rights organization called the National School Boards Coalition, has not yet followed up on her promise to renew her attempts to kill the health clinic, which is set to open during the next school year.

National conservative donors have made it clear that their end goal is for more students to be enrolled in private or charter schools, where the state and federal government have no say in the curriculum.

Klingenstein, who is the chair of The Claremont Institute, funds Lui’s salary. The Claremont Institute is on the board of directors for Project 2025, a conservative blueprint created by the Heritage Foundation for Trump’s second term. It has strong ties to Christian nationalism, the belief that America was founded as a Christian nation and that it should remain that way in all orders of government, including schools.

The education section of Project 2025 aims to establish a parental bill of rights, strengthen a voucher program for private schools and dismantle the U.S. Department of Education.

A voucher system is a long way off for Maine, which has a relatively small number of private schools. The state does have a tuition reimbursement program, where students who live in a town that does not have a high school can choose to attend any public or private school approved by the state, but there have been significant legal battles, some of which went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, over which schools qualify because of their compliance with human rights issues, including gender and sexuality.

The bigger fight in Maine right now, and the one getting the most traction, is over transgender sports policies.

On Election Day, a group called “Protect Girls’ Sports in Maine” set up tables at polling places across the state. According to a social media post, they collected 53,000 signatures in support of putting a referendum on next year’s ballot that would bar trans girls from competing on girls sports teams.

Five school districts have adopted the version of Title IX that excludes transgender students on recommendation from the parents’ rights organization. It’s not clear that those decisions will stand, as they conflict with Maine’s human rights law that allows students to compete on the sports team of their preferred gender.

On Monday, the Maine Human Rights Commission filed suit against the five school districts, citing “hostile” policies on trans students.

If recent debates in St. George, Windham and Livermore Falls are any indication, the issue seems poised to become the next front in the school board culture wars.

“Dismantle the transgender cult,” Lui wrote in a Facebook post promoting the referendum. “Bury it deep.”

Staff Writer John Terhune contributed to this report.

This project was made possible in part through a grant from the Poynter Institute with support from the Joyce Foundation.

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.