Three big takeaways:

- With this final approval, Central Maine Power’s controversial transmission line eight years in the making can complete construction and connect to a Canadian hydropower plant.

- Environmental groups argued the conservation plan does not sufficiently protect mature forest land and maintain habitat connectivity, but state regulators disagreed.

- The connection to Hydro-Québec’s plant will introduce 1,200 megawatts to the New England grid — a move that NECEC says could lower electrical utility costs across Maine by more than $14 million per year.

State regulators approved a 50,000-acre conservation plan this week for the New England Clean Energy Connect transmission line through rural northwestern Maine, clearing a final hurdle for the project’s completion.

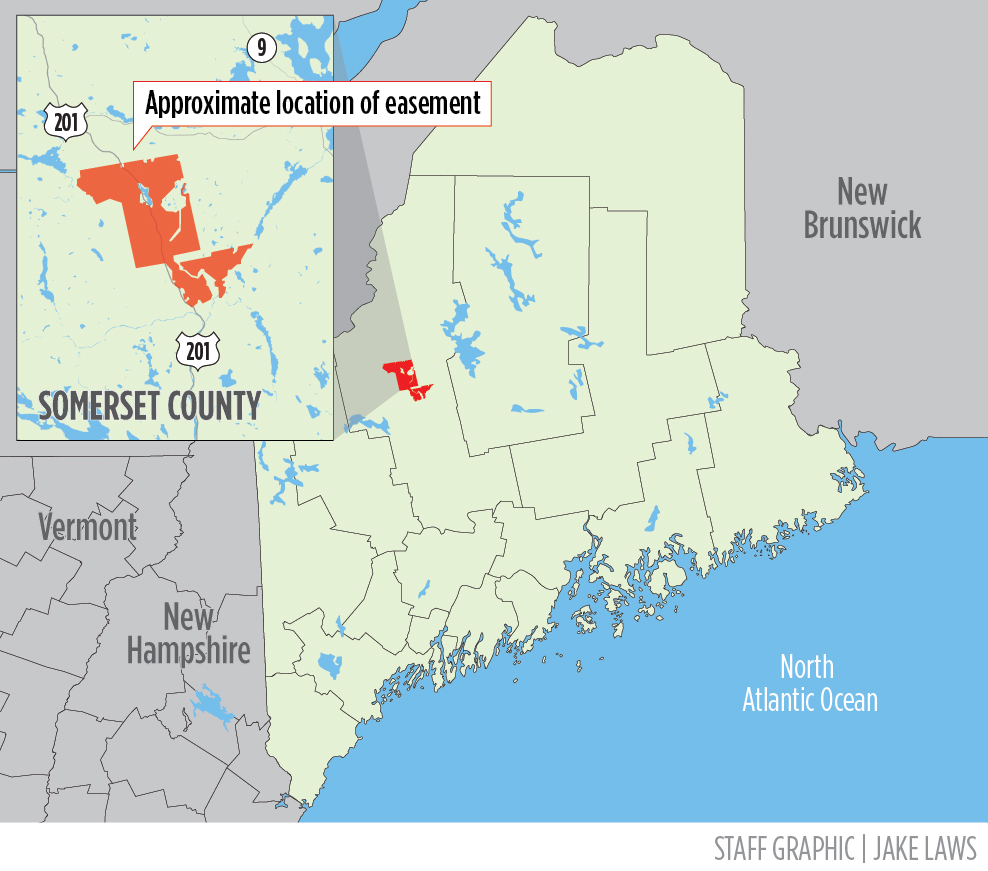

The Maine Department of Environmental Protection’s approval Wednesday marked the end of an eight-year saga to authorize the 53-mile line and connect a Canadian hydroelectric plant to a converter station in Lewiston through remote portions of Franklin and Somerset counties. Construction is expected to be finished by the end of the year.

NECEC, a partner of Central Maine Power Co. and a subsidiary of CMP parent Avangrid, began planning the project in 2017 and faced immediate opposition from Maine-based environmental groups, who said the project would have serious impacts on habitats, scenery and natural resources.

State environmental regulators required the permanent conservation of about 78 square miles near the line earlier this year as mitigation for those environmental and ecological concerns.

NECEC submitted its conservation plan in May. Regulators at the Maine Department of Environmental Protection determined that plan satisfied their requirements.

“This achievement is the culmination of years of hard work, collaboration, and perseverance,” Avangrid CEO Jose Antonio Miranda said in a news release Wednesday. “We have secured every permit, met every regulatory requirement, and overcome significant challenges because we believe we must address the urgent need for reliable energy at a time of rising demand. Today, we stand ready to deliver on that promise.”

Environmental groups argued the proposal didn’t go far enough and should have been rejected. Forests in the area have been heavily harvested, the groups argued, and the value of the conserved land didn’t meet habitat connectivity standards, given that it is split by U.S. Route 201 and other roads and transmission lines. The NECEC transmission line itself requires a 150-foot-wide swath of cleared land.

The groups were especially frustrated with NECEC’s proposals for conserving “mature forest.”

“NECEC came up with their own definition of what constitutes a mature forest and told regulators to wait nearly half a century for trees to just barely meet that flawed definition,” the Appalachian Mountain Club, Maine Audubon, Natural Resources Council of Maine and Trout Unlimited said in a joint statement. “The DEP has wrongly accepted this approach, setting an unacceptable precedent that Maine’s other natural resources agencies urged against.”

WHAT’S IN THE CONSERVATION PLAN?

Following a 29-month permitting process, the Maine DEP required NECEC to develop a plan to conserve land near the transmission line, saying the project would have “substantial impacts” that required extensive mitigation measures to “avoid or minimize those impacts.”

State regulators set a high bar for the conservation area, including promoting habitat connectivity, conserving “mature forest” areas and providing wildlife travel corridors.

Regulators, though, allowed substantial flexibility in which land NECEC proposed to conserve, and how.

NECEC chose a 50,000-acre area owned by Weyerhaeuser Co. — a lumber company and one of the largest private landowners in the United States — which it plans to acquire for an unspecified fee. The parcel is made up of several stretches of forest and wetland that are separated by U.S. Route 201, the transmission line itself and other power lines.

Public access to the land will be guaranteed in perpetuity, even beyond the decommissioning of the NECEC project.

The land will be administered as a working forest conservation easement by the Maine Bureau of Lands and Parks. It connects to 400,000 other permanently conserved acres, creating one of the largest contiguous conservation areas in the state.

As a working forest, the land will be open for logging, except for no-cut buffers around streams and wetlands. NECEC proposed operating the land as a “shifting mosaic” — meaning the location of mature forest to shift over time, as long as at least half of the working forest is mature after 2065.

This was a big sticking point for critics of the project. Habitat connectivity was a central part of the state’s requirements, given the impact of the transmission line cutting through the rural Maine woods.

Environmental groups said maintaining “mature forest” would be nearly impossible if most of the land was open for logging.

The groups also argued that the area doesn’t actually include much mature forest at all. Using remote sensing techology LiDAR, John Hagan, a leading ecologist in Maine, determined that the tree canopy over nearly 80% of the area is less than 35 feet tall and only 7% of the area has trees greater than 50 feet tall.

“The biggest problem with the NECEC proposal is that the 50,000 acres that NECEC selected contains almost no mature forest as typically recognized by both forest and wildlife ecologists – a fundamental requirement for the mitigation plan,” Sally Stockwell, then director of conservation for Maine Audubon, said in a Thursday news release.

But regulators said this week that the proposed land had enough “conservation value” to meet its standards. The DEP cited direct connections to 400,000 acres of conserved land, a lack of specific definitions for mature forest.

Opposition to the NECEC project is not new.

In 2021, Maine voters approved a referendum backed by environmental advocates to kill the project by making such transmission lines subject to approval by the state Legislature.

Combined, the sides spent more than $100 million during the campaign — setting a new spending record for a ballot question in Maine.

Years of legal challenges ensued.

First, CMP challenged the referendum itself, arguing retroactive application was unconstitutional and violated its due process and vested rights. The Maine Supreme Judicial Court agreed and allowed the project to move forward.

Then, environmental groups challenged a lease of about a mile of public land for the project, saying it constituted a substantial change to the land and therefore required a two-thirds majority of the Legislature. Maine’s high court again sided with Avangrid and allowed the lease.

Environmental groups also sued federal permitters over their environmental analysis of the transmission line. That challenge was rejected in April.

WHAT HAPPENS NOW?

With the final hurdle cleared, CMP plans to complete construction, testing and commissioning in the next month and a half.

The line is expected to begin operating by the end of the year.

CMP claims the project will lower energy costs for consumers in Maine by more than $14 million per year, and by more than $150 million in Massachusetts — where most of the energy will end up.

Environmental groups expressed concerns that Wednesday’s approval will set a dangerous precedent for future developments. The DEP’s decision to use specific species as indicators and adopt the “shifting mosaic” approach will harm species that need mature forests not just along this corridor, but in other areas, too, the groups said.

“For one of the highest-profile development projects in years, the DEP is saying for the purposes of compliance for this project — and this project only — we will define ‘mature forest habitat’ in a way that future regulators can ignore,” said Luke Frankel, a staff scientist at the Natural Resources Council of Maine. “This is not the way a state regulatory agency should operate. The way to avoid bad precedent is simple: don’t set it.”

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.