A new book is making its way into classrooms and libraries across the state, detailing the stories of Holocaust survivors living in Maine.

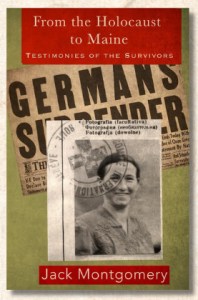

Freeport-based photographer Jack Montgomery will speak at the Freeport Community Library at 5:30 p.m. Tuesday, Jan. 20, sharing the stories of Jewish survivors of the Holocaust who moved to Maine from his book, “From the Holocaust to Maine: Testimonies of the Survivors.”

The Maine Jewish Museum will also hold a book launch for “From the Holocaust to Maine” at 5:30 p.m. Thursday, Jan. 22.

Ahead of the event, Montgomery told The Times Record about his research efforts, providing new angles on the Holocaust and its aftermath.

Why did you decide to pursue this type of work with Holocaust survivors?

I became aware of the Holocaust when I was 9 years old; I saw a Life magazine [article] about Anne Frank. I knew nothing about it — I grew up in a very Episcopal household and community — but I was stunned and appalled even at 9 years old, and that has never left me.

So, when I progressed in my photography 35 years later, and got interested in portraiture, I was looking for a project to give me some structure in what I was doing. It occurred to me that photographing the Holocaust survivors would be the project in keeping with something that I am going to focus on my whole life.

I was a lawyer at the time, and one of my partners, named Sumner Bernstein, was very active in the Jewish community. I went to him asking for help in setting this up, and he put me in touch with the Holocaust and Human Rights Center of Maine. This was about 1993-1994, and so I completed the portraits of all the Holocaust survivors in Maine I could find.

It became an exhibition at the State House and libraries, and is now a permanent exhibit at the Maine Jewish Museum and at the Holocaust and Human Rights Center. [The Holocaust survivors] were 19 to begin with, and then one more was added later.

When I was doing these pictures, I would talk to folks and hear their stories, which were remarkable. I was impressed not only with their courage and persistence, but with their ability to rebuild their lives here in Maine.

At the beginning of the pandemic, it occurred to me that if anybody was going to write the book, it was going to have to be me. So, I spent four and a half years compiling their stories from interviews and books and poems they had written. Their families were very helpful in giving me more material, and that became the book that was first published in August of last year.

Are there any parallels you found in these stories to the present day?

It is hard to ignore when you look at how the Nazis took power and then dehumanized an entire subset of their population. Dehumanization is one common thread. The Nazis, and Hitler in particular, would refer to the people he hated as animals, as scum, as rodents, as rats.

Any time you find people in power dehumanizing, it is disturbing. The problem is, in my opinion, we are all born with a capacity for empathy, and so how do you get somebody who is willing to push a 5-year-old weeping child into a gas chamber? That is not a normal thing for a human being to do, but it was because of a very structured and thoughtful sense of dehumanization that hundreds of thousands of Germans were persuaded to take part in the Holocaust.

When I see a leader, whether it’s in this country or another country, whether it’s somebody on the right or left who is using dehumanization to acquire power and to assert power, I find it extremely disturbing.

What was researching this project like?

I spent almost full time on this for four and a half years, and so I had access to interviews that were done of these survivors and other materials, but I also had to do a significant amount of historical research. I was fortunate to have the assistance of two scholars, who really helped a lot.

At the end of the book, there is a very extensive appendix, which is intended as a resource for anybody who wants to dig deeper.

There is another aspect if you were to say to me, how do you expect the book to be used? Here’s what I would say. It has been distributed to every school grades 6–12 in the state. It is about to be distributed to every library in the state without charge because we were very fortunate to have some significant financial support from people in the community who recognize the importance of preserving these stories.

In addition to that, the Holocaust and Human Rights Center of Maine, through its in-house scholars, is producing a teacher’s guide that will be available to every school in the state. The expectation is [that] the book will serve as a primary resource for teaching the Holocaust to students. Now and in the future.

What takeaways would you want young people reading your book to learn from?

The first thing is, I want people to walk away with an appreciation of the strength of these people who survived horrific circumstances and rebuilt their lives. I hope others will find that inspirational, as I did. Second, I hope people will recognize the reality of the horror of what occurred.

There is a movement now that, unfortunately, is growing, which is seeking to either diminish or deny the Holocaust altogether. I hope people reading this will realize these are primary sources; these are the folks who actually lived it.

The last thing is that at least some people will be ready to stand up and speak out against the type of prejudice and violent behavior against minority groups. That takes courage, and I hope the book will inspire some people to do [the same].

Without giving too much of the book away, how did some survivors end up in Maine?

Many of them came sponsored by family members living in the United States. It wasn’t easy to get to the U.S. from war-torn Europe.

Then, they came to Maine just by happenstance. One of them, Dr. Julius Ciembroniewicz, was in Boston, and he became a doctor. He enjoyed fishing in Maine and concluded that this was where he wanted to be.

Another great story is [that of] Jutka (Judith) Magyar Isaacson, who became a dean of students at Bates and was on the board of Bowdoin College. After the end of the war, she was foraging for food and she met a young U.S. Army officer named Irving Isaacson, who was a lawyer in Lewiston. They fell in love, got married, and came back and started a family here.

Her mother, Rose Magyar, who survived Auschwitz with [Judith], came with them, and so they rebuilt their lives in Lewiston. [Judith] got a college degree, then advanced degrees, and became a very prominent person in the Maine University system.

One more thing I should mention is that there are only two [Holocaust survivors] still living. One of them, Charles Rotmil, died last fall, but I was very happy to put a book in his hands before he died. There is one living in Portland, and one has moved to North Carolina, and that is it; when they are gone, it is done.