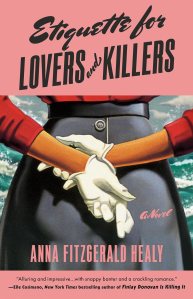

Life in Eastport in the 1960s is dangerously seductive for Billie McCaddie, the plucky protagonist of Anna Fitzgerald Healy’s debut novel, “Etiquette for Lovers and Killers.”

“I’m starting to realize that some dreams don’t come true,” Billie says. “That I’m not going to just wake up some morning as an ingénue in a Brontë romance, because Eastport is about as far from ‘Wuthering Heights’ as you can get.”

While Billie is a dreamer, the novel itself was born out of a dream Healy had one day. The Bar Harbor native felt frustrated that she couldn’t find a book that combined the joy she found in reading both romance and mystery. A fateful nap presented the novel’s premise to her, which compounded with thoughts on her family in Eastport. Since her debut novel published last July, Healy has felt “seen and understood,” she said. “I never imagined that my weird, little brainchild would resonate with so many people.”

She spoke with the Portland Press Herald about life in Eastport, summer tourism and her hopes for the nascent “romystery” genre.

The setting is a huge part of the novel’s tension. Billie falls in with a crowd of privileged summer people. What inspired you about Eastport, and how did it feed the novel’s plot?

I once read that every book should be set in an interesting place and time, which might not be universally good advice, but it’s good advice for me. I like being transported, and I also like research. This idea about Eastport in the ’60s allowed me to do a deep dive into my own family history and a time period and place that I love.

I didn’t set out to write a love letter to my family, but that’s what happened in the process. I feel lucky that I grew up so connected to the past, and I love how Eastport embodies that. I grew up in Bar Harbor, which is commercial and the Disneyland version of Maine in some ways. I grew up looking at these mansions, wishing I could get invited inside. My work has allowed me to visit some of the grand old houses in the United States, and I drew from some of those mansions when I was creating Webster Cottage. Everything is warm, cozy, threadbare and smelling slightly of fish in Eastport, and then everything is hard, cold, pristine, luxurious and horrible in Webster Cottage.

The novel presents a strong class narrative. How did the time period and focus on social etiquette invite you into that exploration?

They’re so deeply connected. My family was very working class. My grandfather had a boat-slash-refrigerator-repair shop. I grew up with my grandmother’s copy of “The Amy Vanderbilt Complete Book of Etiquette.” It naturally progressed into my own meditation upon politeness and how I navigate my own desire to see these people in the 1% with my own working class roots.

As Billie investigates Gertrude’s murder, she increasingly identifies with her. How did you want to interrogate or complicate the genre of “dead girl stories”?

My biggest pet peeves are all of these stories where it’s murder on page one and we have no idea who the victim is, or she’s just this sweet, dear thing. I hate that. Come on. We all have more imagination than that. I love that Gertrude becomes a villain, and we learn who she is over the course of the book. I don’t really like good girls. I think it’s much more interesting if we’re all a little bad. It took many drafts for me to come to the truth of Gertrude, but by coming to that, I also came to the truth of Billie. One of my favorite books is “Rebecca.” I love that Rebecca is a villain, but I hate that the nameless protagonist is such a good girl. When I had this initial spark, I was thinking a lot about “Rebecca” and thought, “What if I turned this idea on its head? What would happen then?”

Along these lines, the book meditates on how women writers across time have built writing careers within genre fiction. How were you interested in the gendering of genre fiction?

Publishing and writing is largely male dominated. We see Steinbeck. We see Hemingway. We see these giants, and they are men, and they are writing “fiction.” Meanwhile, women like Patricia Highsmith dominated that genre. The Brontës killed it with Gothic romance. I’m not sure why it’s always women. Maybe society likes to put us in little boxes, and it’s safer, perhaps, for women to focus on one box rather than the huge animal of fiction. I’m generally a fan of thinking outside of the box, which is why I’m thinking about writing something in a different genre.

In your author’s note, you wrote about wanting a book that brings together Patricia Highsmith and Jane Austen. What’s inspiring you within this intersection of love and crime?

I’m currently reading “The Price of Salt” by Patricia Highsmith. I love that it’s not a murder mystery, but her attention to detail is absolutely breathtaking. Julia Seales wrote “A Most Agreeable Murder” and “A Terrible Nasty Business.” I’m rereading her novel, which is a Jane Austen-style murder mystery set in the Regency period. I love how over the top, ridiculous and “Bridgerton” it is.

I was inspired by romantasy as well. I loved how risqué some of it was, and it made fantasy more socially acceptable to read. It threw a huge spotlight on this genre. I’m excited about bending genres, playing with them, and seeing what happens. I’m focused on romance, and I love crime as well. Life is sort of like a spritz. We need the acidity, but we also need the sweetness to balance it. This is the start of the “romystery” genre. I feel like it’s been there, and it’s been wanting to come out of its shell for a long time. We all love the drama. We all love the spice, and there’s no need for them to play separately.

Michael Colbert is the editor-at-large for books.

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.