At sunset on March 9, 1945, 30 officers from the Maine State Police, Maine Warden Service, Somerset County Sheriff’s Office, and FBI gathered around a hot wood stove at a World War II German prisoner of war camp in Hobbstown, a remote western Maine township. The previous day, three Germans had escaped from an ice-harvesting job.

After failing to capture the German soldiers, distraught officers grappled with a vexing question: Should they seek the help of Bill Hall, a woods-wise hermit who had lived nearby since the early 1930s?

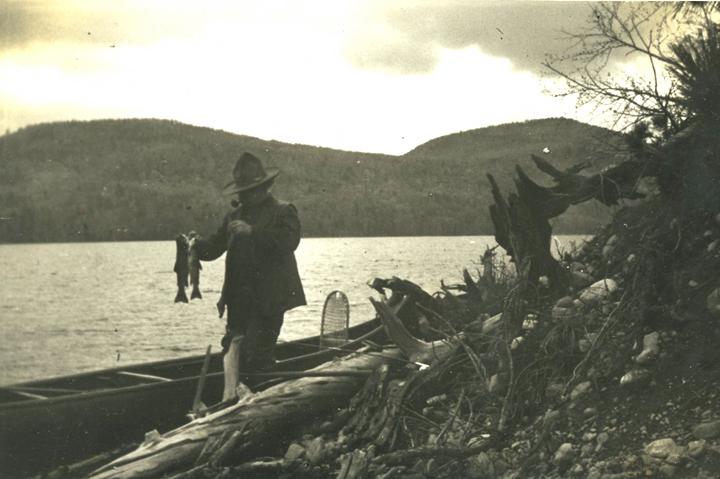

Dean Yeaton, then in his teens, had befriended the prickly hermit while working at his father’s logging camp in Hobbstown. “Hall could track a weasel across three townships,” Yeaton told me years later. “He damn sure could find the Germans.” Although it embarrassed law enforcement officers, a sheriff deputized Hall on March 11, 1945.

The following day, Hall directed game wardens to West Forks — a logging community 30 miles through snow-covered Maine woods from the POW camp — where the Germans were apprehended, bringing an end to one of the largest manhunts in state history. “Years later,” Yeaton told me with a laugh, “whenever Hall and I met in the woods, he displayed his bronze sheriff’s badge, brandished a six-shooter, and recited a line from his favorite Zane Grey western: ‘Son, in these here parts, I’m sheriff.’”

From the 1930s to the early 1950s, the hermit lived in a 10×12-foot log cabin on Fish Pond, 18 miles east of the Quebec border. His nearest neighbor lived in Jackman, 30 miles away by canoe. That changed during WWII when a gravel road was bulldozed 19 miles through wildlands to construct a German POW camp two miles from Hall’s cabin. The camp’s 250 POWs were members of General Rommel’s elite Afrika Korps, captured in May 1943 when the Allies defeated the Germans in Tunisia and Morocco. Most had picked cotton in Louisiana before being shipped to Hobbstown to cut pulpwood.

Although the POW camp encroached on Hall’s lifestyle, the hermit steadfastly clung to his independence. Dozens of jars of pickled and smoked trout and perch were stored in his root cellar, along with bushels of potatoes, carrots, onions, turnips, cabbages and apples. Each year he cut and split 12 cords of yellow birch, rock maple and cedar kindling to heat his drafty cabin.

“About once a month,” Yeaton recalled, “when the pond was ice-free, he washed clothes by dragging them behind an Old Town canoe.” When river drivers once discovered his union suit snagged on floating pulpwood, they hung the undergarments on a shoreline tree. Hall retrieved his long johns and nailed a note to the trunk: “Please iron next time.”

When blizzards hindered trapping of beaver and other furbearers, he stoked his wood stove and made deer hide moccasins, cooked beavertail soup thickened with cattail roots, cut cedar shakes with a froe and mallet, whittled moosewood door handles to replace broken ones, and sipped homebrew.

Born in Solon on Christmas Day, 1872, Hall found childhood joy exploring the woods. After graduating from Gould Academy in Bethel, he returned to western Maine to hunt, fish and trap.

“Hall was an odd, likeable fellow,” Yeaton said. “Year-round he wore dark green wool pants and a wool shirt. As a teen I visited him during the winter. Stacks of frozen beaver pelts on his porch and deer hides tacked to outside cabin logs made quite an impression on me.”

One April during the Great Depression, Hall loaded a wooden sled with furs of beaver, mink, otter, fisher and lynx. Using homemade snowshoes, he hauled the sled eight miles to a canoe he stored below Moose River’s Spencer Rips. From there, aided by the spring freshet, he paddled his valuable cargo to a fur buyer’s trading post in Jackman.

Making double the money he expected, Hall skipped mud season by hitchhiking to Waterville, where he boarded a passenger train for Boston and New Orleans.

“He was robbed his first night in New Orleans,” Yeaton said. “Sticking a revolver in Hall’s ribs, the robber said, ‘Give me your money.’” The hermit emptied his wallet of his winter’s earnings. The thief pushed the gun in further and said, “Give me all of your money.” Hall emptied his pockets of coins. Satisfied, the thief turned and walked away. Hall followed him, keeping a safe distance until he could make his move. “The mugger,” Yeaton said with a laugh, “had no idea that he had just robbed a highly skilled Maine woodsman. Nor did he know that competent Maine trappers also carried pistols.”

When the thief turned into a dimly lit alley, Hall closed in. Sticking his pistol into the man’s ribs, Hall said, “Give me back my money.” The robber complied. Hall added, “including my coins. And while you’re at it, give me your gun and two bucks.” In no position to argue, the mugger complied. Satisfied, Hall walked away.

Back in Hobbstown, the hermit retold the story many times to Yeaton, “Yessiree, I got my money back and collected a little interest fee as fair compensation for my troubles.”

Hall’s solitary life, though, was upended by the POW road that opened the region to travelers, including a young Baptist missionary who paid Hall an overnight visit. The hermit politely listened to the proselytizing before taking the missionary on a sunset canoe paddle as trout rose and hundreds of ducks descended on a marsh. That evening, serenaded by hooting owls and singing whip-poor-wills, Hall spoke up, “Young fella, these woods and waters are my church.”

The following morning the missionary was awakened by the crack of gunshot inside the cabin. Hall, who had lifted a trapdoor to his root cellar, had shot a woodchuck stealing carrots. Told that woodchuck stew would be served for supper, the missionary hastily departed for civilization.

In the spring of 1952, at age 80, Hall moved into a Catholic nursing home in Bethel. He cussed when administrators forbade him to swear, smoke a pipe or chew tobacco. When a young nun asked how often he bathed, Hall replied, “Twice a year — New Year’s Day and July 4th. More than that causes wrinkled skin.”

The hermit died on March 13, 1958. His obituary stated, “He was a man of unique character, frank spoken, (with) a great gift of humor and sterling qualities.”

In the 1970s, I found Hall’s journal inside a dilapidated POW officer’s cabin. His Dec. 26, 1938, journal entry was particularly poignant because he had spent another Christmas alone: “Awoke Christmas morning to an eerie dark cabin on account of a blizzard. Took me prit’ near an hour of shoveling to clear the windows. Celebrated yesterday with a quart of homebrew, a crock of baked beans and fresh venison. Reread Gone with the Wind and Green Hills of Africa. Hoping for a January thaw to wash clothes and take a bath. Haven’t done either since the pond iced over in November.”

The old-timer embodied an era when Maine hermits spurned conventional lives for self-sufficient ones. Like the woodland caribou that once fed and clothed them, Maine’s colorful hermits are now extinct. Hall’s journal entry, dated Dec. 31, 1939, captured best the timeless appeal of trading life’s material trappings for a simple log cabin deep in the Maine woods: “Farewell to another year. Blessed am I to be living in the land of milk and honey.”

Ron Joseph of Sidney is author of Bald Eagles, Bear Cubs, and Hermit Bill: Memories of a Maine Wildlife Biologist, published by Islandport Press

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.