“The caribou project is a Christmas gift to the State of Maine,” Glenn Manual, commissioner of the Maine Dept. of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife, December 1986

In October 1986, an ad hoc committee invited Dr. Mark McCollough to the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife office in Augusta.

“I wasn’t in Commissioner Manuel’s office more than five minutes when he asked, ‘Would you be interested in leading the project to reintroduce caribou to Maine?’” McCollough recalled. Newfoundland had agreed weeks earlier to provide caribou to Maine.

Despite reservations, McCollough accepted the job.

“I was excited about the position,” he said, “but very little planning had been done, money hadn’t yet been raised, the logistics for transporting caribou were lacking, and it wasn’t fully decided where in Maine the nursery herd would be held. And I had just six weeks to implement a high-profile, complex wildlife project involving two countries.”

In early December 1986, Newfoundland biologists in helicopters captured 35 caribou with tranquilizer darts. Unfortunately, 13 died during capture and transport to Maine. The survivors were trucked across Newfoundland in a blizzard. At Port-aux-Basques, in 80 mph winds, the cattle truck with the sedated caribou rolled onto a 567-foot ferry, the MV Caribou, and was fastened with heavy chains.

“The terrifying 125-mile crossing to Sydney, Nova Scotia,” recalled McCollough, “was like scenes from The Perfect Storm. Halfway across, amid 60-foot waves, the bow buckled, bending steel I-beams. Emergency pumps kept the ferry afloat. At one point, as it became top-heavy with sea ice, the alarmed captain said, ‘We may have to ditch the ship.’”

In Sydney, the MV Caribou discharged the caribou truck, which traveled in blinding snow through New Brunswick and Maine, then spent the next six months being repaired at a dry dock.

Prior to the caribou’s arrival, the ad hoc committee had decided to house the animals in a 13-acre enclosure at the University of Maine in Orono. The advantages were numerous: The university’s veterinarians could administer care to injured or sick caribou, wildlife professors could assist, students could help feed and care for the caribou, and the public and media had easy access for viewing the herd. But there was one big disadvantage: Orono’s large deer herd was infected with brainworm — a parasite lethal to caribou and moose but not deer. Knowing that, veterinarians treated the caribou with ivermectin, an antiparasitic drug.

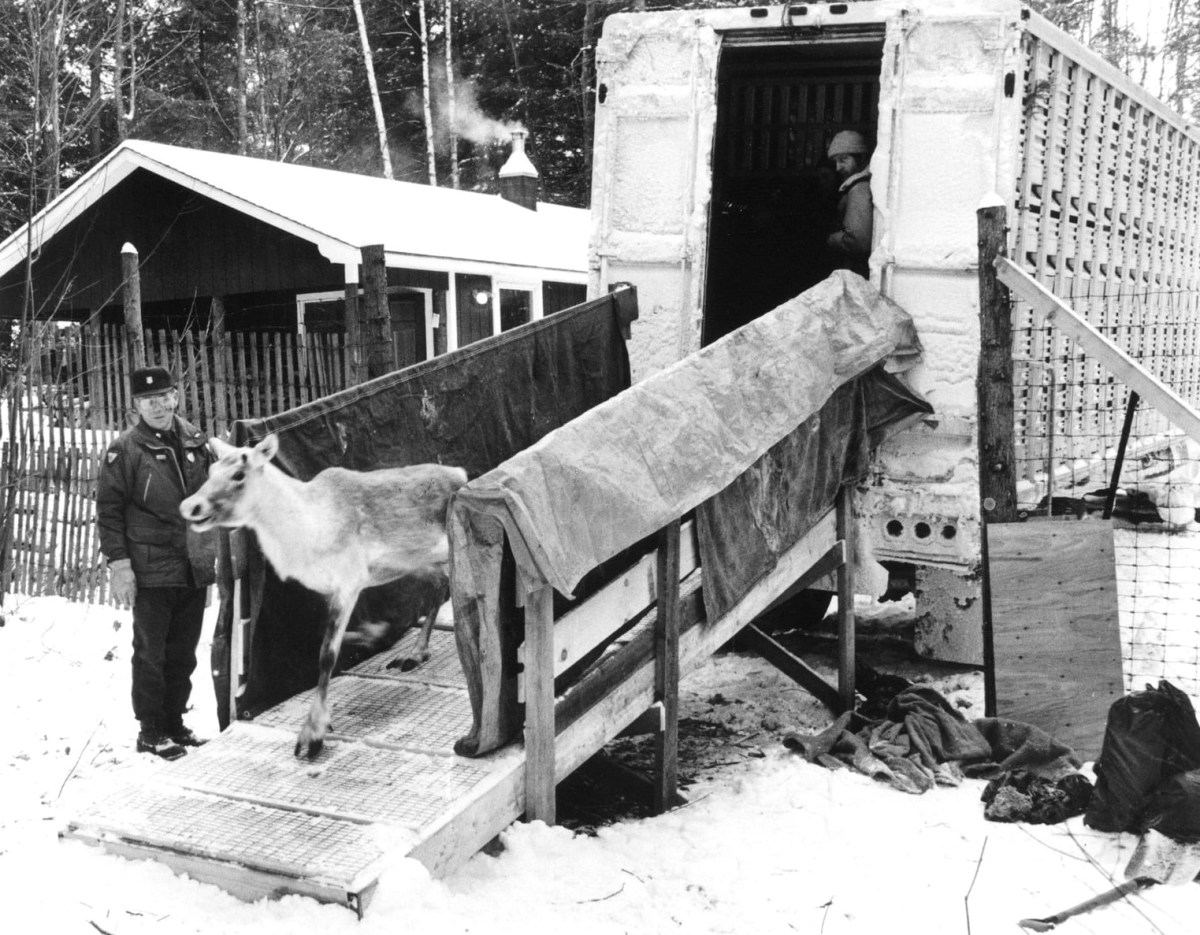

On Dec. 10, 1986, the harrowing 1,200-mile journey ended when 22 woodland caribou (two bulls and 20 pregnant cows) stepped unsteadily from the weather-beaten cattle truck and into the university’s fenced enclosure. Their arrival marked Maine’s second attempt to reestablish caribou.

The first reintroduction occurred in December 1963 with the release of 23 Newfoundland caribou in Baxter State Park. The project boosted Maine’s spirits mere weeks after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination. As an 11-year-old, I sat mesmerized in front of a black-and-white television watching grainy footage of caribou being lowered in harnesses from an Army National Guard helicopter. The footage aired on Bud Leavitt’s Saturday night outdoor television show in Bangor. Leavitt’s program and baked bean suppers were a Saturday staple in our home. (My three siblings and I sang along with the show’s theme song, “The Happy Wanderer.”) By 1965, all 23 animals had died or migrated to Canada.

Historically, western and northern Maine was home to thousands of woodland caribou, but by the early 1900s, the caribou population had crashed due to market hunting and the spread of brainworm-infected deer into northern Maine. In 1898, at a Sportsman’s Show at Madison Square Garden, Cornelia “Fly Rod” Crosby — the state’s first and most celebrated registered Maine guide — claimed that she shot the last Maine caribou. But in 1911, Aroostook County Game Warden Bert Spencer documented Maine’s last known caribou herd along Burntland Brook, a tributary of the fabled St. John River.

The 1986 caribou project also galvanized Mainers. Most favored reintroducing caribou because earlier generations had contributed to their demise. The cooperative Canadian American caribou project became an international sensation. According to the late Paul Fournier, then public information specialist of the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife, caribou media coverage exceeded anything he’d seen. “It was much bigger than Maine’s 1980 moose hunt,” Fournier said years later, “and that was a big deal — the first hunt since 1935.”

Media outlets from Japan to Sweden arrived in Newfoundland in December 1986 to film caribou captures and interview biologists. CBS Evening News and the Canadian Broadcasting Company news clips were watched by millions of Americans and Canadians. “The media,” Fournier said, “followed the caribou truck from Newfoundland to Orono. It was a circus that required managing for the well-being of caribou and biologists.

“Although most of the animals were in reasonable shape in Orono, two were carried from the truck on stretchers,” said Fournier. “A few stressed animals died in transport. Given the stormy crossing of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, it’s amazing we didn’t lose more caribou.”

“Watching caribou exiting the truck on campus was an emotional high and a relief,” McCollough said. “Several hundred people who’d been glued to the television and print media news greeted us at the university’s deer enclosures.”

Between 1987 and 1989, the birth of 50 caribou calves in captivity represented a milestone. Newborns prompted Girl Scouts to sell baked goods and organize bottle drives to raise funds for the animals.

“It was also gratifying,” McCollough said, “to observe the joy of 86,000 Mainers visiting the pens to see a once-native species.”

The greatest setback was the high number of caribou deaths in Baxter State Park. The first release, in April 1989, included 14 young caribou raised in Orono. Approximately half were killed by bears and the others died of brainworm.

“January 1990 delivered an unexpected blow,” said McCollough. “The Baxter State Park Authority denied our request to release additional caribou. Great Northern Paper Company kindly offered a release site near the park for the remaining 20 radio-collared caribou. But most of these were dead by October 1990.”

It was devastating and emotionally draining for McCollough to face the media when the animals kept dying. Jane Goodall, the late global wildlife-conservation icon, spent an afternoon with McCollough at the caribou pens.

“She was very sympathetic,” he said, “as were many Mainers who appreciated what we were attempting to accomplish.”

In retrospect, a restored caribou herd would have been a remarkable achievement, on par with Maine’s successful bald eagle and peregrine falcon restorations. Today, McCollough acknowledges that it would have been difficult for woodland caribou to survive.

“Climate change is affecting Maine’s snow regime,” he said. “Caribou require deep, fluffy snow. Their large hooves are adapted to pawing through it to expose nutritious ground lichens. In recent years we’re getting more rain events in winter, and layers of ice on top of snow makes feeding nearly impossible — the food is there but they can’t get to it. I’m still asked if Maine should attempt another caribou-reintroduction project, but I don’t think it’s possible now.”

Ron Joseph of Sidney is author of Bald Eagles, Bear Cubs, and Hermit Bill: Memories of a Maine Wildlife Biologist, published by Islandport Press

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can update your screen name on the member's center.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.