With complicated datasets drawn from decades of monitoring, information about the conditions of Maine’s waterbodies has been difficult for the public to access or understand, according to state scientists and Lake Stewards of Maine.

That’s why a scorecard interpreting that data will be a helpful tool for residents and visitors who want to understand the health of the waters they enjoy, said Alison Cooney, executive director for the Lake Stewards of Maine.

“The idea is to have people look at the score, and then as you drill down (on the waterbody profile), it talks about how the score was created, and then how to get involved,” Cooney said.

The new scorecard was created by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection and is hosted on the Lakes of Maine website, which is owned and managed by the Lake Stewards of Maine. DEP oversees the framework and data compilation, while Lake Stewards contributes much of the long-term monitoring data for water quality and invasive plants.

“We have had conversations about doing something like this for many years,” said Jeremy Deeds, aquatic ecologist for Maine DEP. Deeds said his counterparts in Vermont developed a scorecard about 15 years ago.

“That served as a great starting point for us,” he said. “We started pulling information together and drafting ideas about a Maine lake scorecard about two years ago.”

The scorecards are designed to be a public-facing resource, not a regulatory tool, giving residents, shoreland owners, conservation groups and visitors a clearer way of seeing where their lakes are thriving and where pressures like development or invasive species might be building, Deeds said.

“The goal of the scorecard is to help people interpret the large amount (in some cases) of lake information we have and how it relates to individual lakes,” Deeds said. “We want to give people that are interested in lakes a starting point to support conversations about lake health.”

Deeds said he hopes the scorecards will help identify and prioritize improvement actions on “a case-by-case basis.”

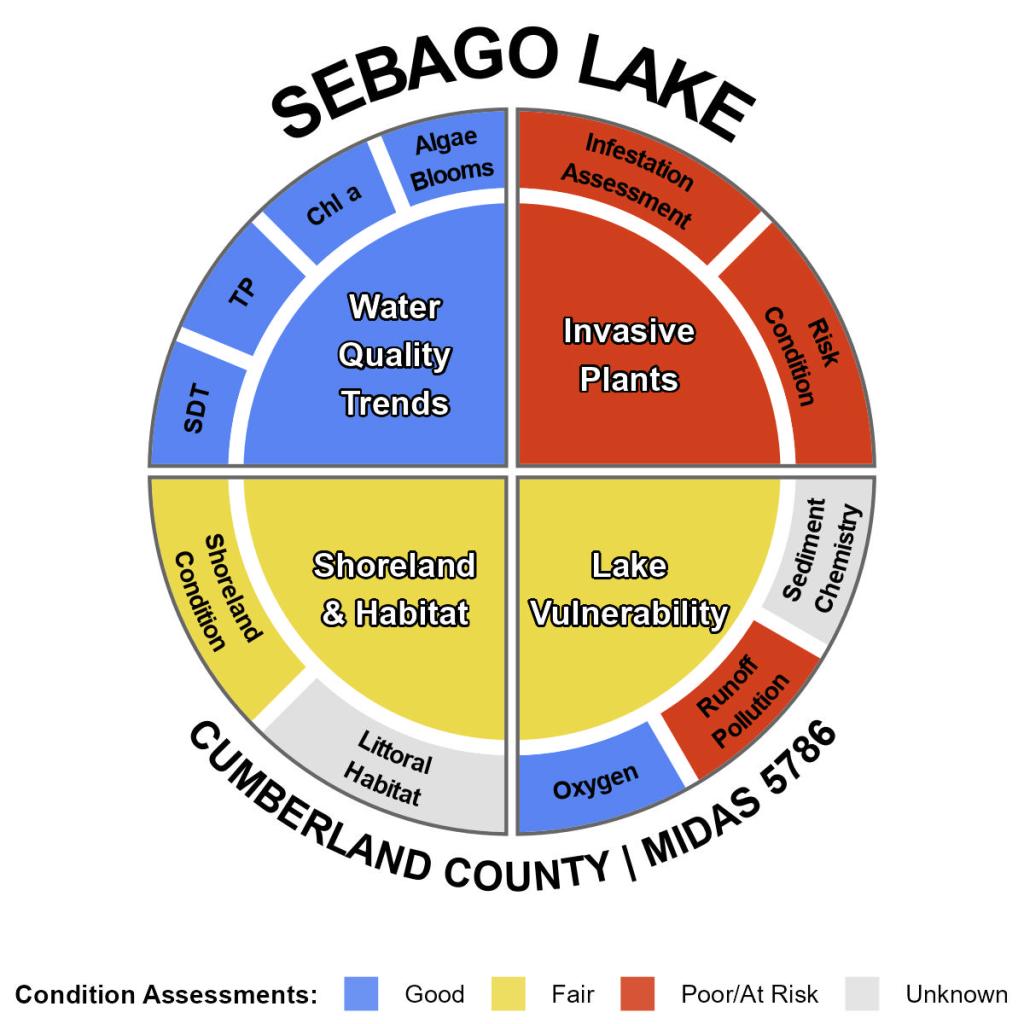

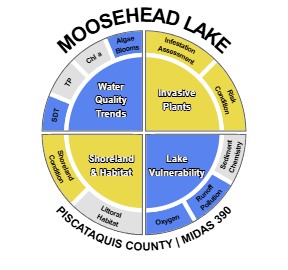

The scorecard breaks waterbodies down to four categories: water quality, invasive plants, shoreland and habitat, and lake vulnerability. Deeds said each of the four categories on the scorecard are accompanied by collections of links, resources and contacts “to help people take an active role in the protection and enhancement of lakes they are interested in.”

Each category also has subcategories. Water quality, for example, is broken down into SDT, or water clarity, total phosphorus, chlorophyll and algae blooms. Invasive plants consist of infestation assessment and risk conditions, shoreland and habitat consists of shoreland condition and littoral habitat, and lake vulnerability consists of oxygen, runoff pollution and sediment chemistry.

The categories and subcategories are color coded, blue for “good,” yellow for “fair,” red for “poor/at risk” and gray for unknown, which means data has not been gathered for that particular subcategory. Furthermore, while Maine has about 6,000 waterbodies, only those with sufficient data across one or more categories were included in the scorecards.

Deeds said over 20 lakes scored blue across water quality trends, shoreland and habitat and lake vulnerability, though additional high-quality lakes may be underrepresented due to remoteness. These are lakes that tend to share common traits like limited human activity or deep water or geology that reduces nutrient inputs.

Only a few lakes scored red across the same categories, Deeds said. Those waterbodies typically have long histories of watershed use, development and phosphorus loading which fuel algae blooms.

‘EVERY LAKE IS UNIQUE’

One thing the scorecards are not meant to do is to compare waterbodies against one another. “The idea isn’t to compare it to other lakes,” Cooney said. “It’s just looking at individual lakes. Every lake is unique.”

Sebago Lake, for instance, scores good for water quality, fair for shoreland habitat and lake vulnerability, but is rated poor or at risk for invasive plants. The three main concerns for the lake are invasive plant infestation assessment and risk condition and runoff pollution.

Moosehead Lake — much farther north and different in its depth, shoreland and habitat, for example — is rated good for water quality trends and lake vulnerability, specifically for SDT, algae blooms, oxygen and runoff pollution. Invasive plants and shoreland and habitat are considered fair.

Out of 413 waterbodies tested for water quality, 70%, or 291, were rated “good.” Some 82 waterbodies were rated “fair” while roughly 10%, or 40, were classified as poor or at risk. The majority of waterbodies, some 778, are listed as “unknown” for water quality trends, reflecting gaps in recent or consistent monitoring.

Nearly 90% of waterbodies, or 930, were rated fair for invasive plants while roughly 12%, or 124, were considered poor or at risk, indicating presence of invasives or heightened proneness.

Lake vulnerability showed a relatively even spread with 381 waterbodies rated good, 375 fair and 324 poor or at risk.

Data show that shoreland and habitat generally fared better, with 504 rated good and 612 rated fair. Just over 54 were considered poor or at risk.

Lake Stewards of Maine plays a central role in two of the scorecard’s four categories — water quality and invasive plants — and about 85% of data collected over many years has been by volunteer community scientists: “People we’ve trained,” Cooney said, adding that Lake Stewards of Maine and DEP provide certification for water quality and invasive plant monitors. Anyone can get the training for free, she said.

Cooney said volunteer monitoring is essential due to the scale of Maine’s waters. She said every subcategory is important, but gray scores are a good example of what communities or individuals can focus on for monitoring efforts.

“The role of citizen scientists, here, is huge,” Deeds added, crediting groups like Lake Stewards of Maine, Maine Lakes, Lakes Environmental Association and 7 Lakes Alliance for their large roles in data gathering.

Maine Lakes’ LakeSmart program works with shoreland owners to reduce runoff and improve habitat while Lake Stewards of Maine and DEP support invasive species early detection and prevention, Deeds said. DEP also offers watershed grants, training and technical assistance to help communities address runoff.

“There are 6,000 lakes in the state of Maine and there’s no way professionals could go out and monitor all those lakes,” she said. “There are things that we can do, people can do, to help improve those scores.”

Staff writer Penelope Overton contributed to this report.

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.