Buried in the reports, photos, logs and the mountain of information related to one of the state’s most extensive missing person searches, there is this detail: Geraldine Largay did not know how to use a compass.

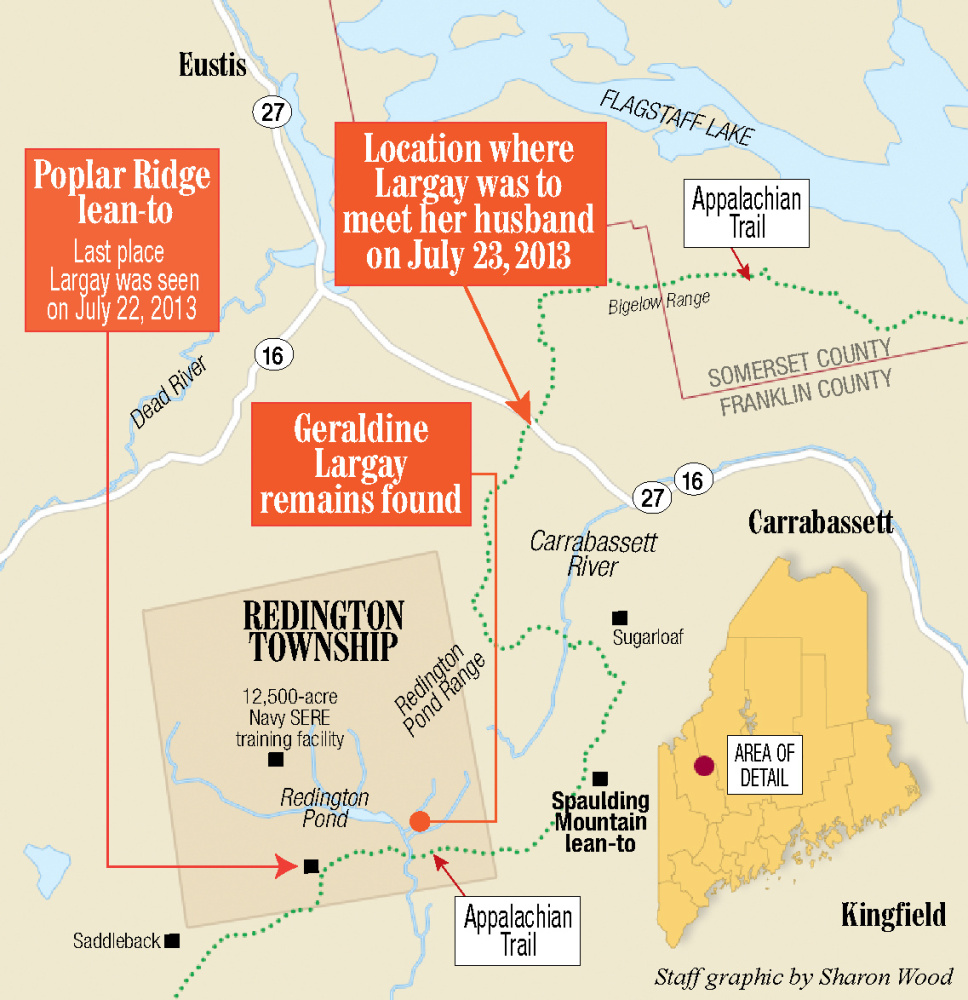

Largay’s remains were found more than two years after she disappeared July 22, 2013, on the Appalachian Trail in Franklin County, but until the 1,500-page report was released Wednesday by the Maine Warden Service, much of what had happened to her still remained a mystery.

Of all the indications in the report that Largay, 66, wasn’t prepared for the nearly 1,000-mile hike that eventually claimed her life, the fact that she didn’t know how to use a compass is the among the most startling.

“That would be a recipe for disaster,” retired Game Warden Roger Guay said Thursday night.

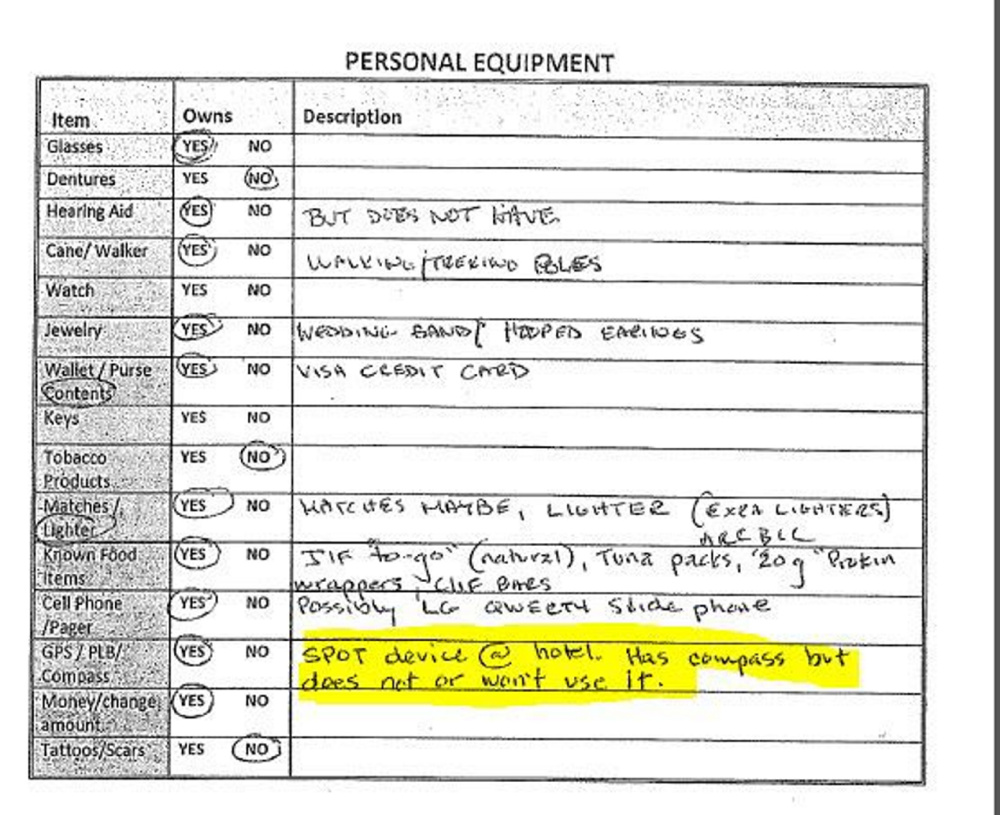

A compass was found with her belongs at the campsite she’d fashioned in the woods while she was lost, but a reference on a missing person report in the case file, as well as a summary from an interview with Largay’s friend and hiking companion Jane Lee, said she didn’t know how to use the compass.

Lee “told me (Largay) did not know how to use a compass,” the report said. “She didn’t know if Geraldine even had a compass.” It’s not clear who the report is written by.

An inventory list in a missing person report in the case file said that Largay also left her SPOT GPS device behind in a motel and “has compass but does not or won’t use it.”

Guay said a compass is an essential tool for anyone out in the woods. “You can get caught in heavy fog and you can get off the trail,” he said. “You don’t venture into the wilderness without a compass. You’ve got to have that knowledge.”

EASY TO GET OFF TRACK

Guay was not involved in the Largay search, but was involved in so many searches in the Maine woods in his 25 years with the Maine Warden Service that he can’t keep count. He said he is not qualified to speak about specifics of her case, but there is one thing he is sure of: “In this corner of the world, it is a lot easier to get off track.”

The items in the Largay case file include excerpts from a journal Largay kept during her last weeks alive in the rugged woods of Franklin County, and paint a grim picture of the worst scenario for a thru-hiker of the 2,184-mile trail. Largay, of Brentwood, Tennessee, who went by the trail name “Inchworm,” was hiking the second half, and had started in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.

She had less than 200 miles left to go and she’d already come 950 miles. But she was in what’s considered the most treacherous part of the trail that begins on Springer Mountain, Georgia, and those familiar with hiking and search and rescue along Maine’s section of the Appalachian Trail say it only takes a few missteps in hiking or planning for that to occur.

Things that Largay did, such as hike alone, leave her GPS locater behind in a motel, stay in one place after she became lost from the trail, and not use her compass, all decreased the likelihood that she would be found, despite what has been described by game wardens as the most extensive search of its kind it the state’s history.

Largay was reported missing on July 24, 2013, after she didn’t appear at a designated meeting with her husband George the previous day where the trail crosses Route 27 in Wyman Township.

In October 2015, her remains were found in her sleeping bag zipped inside of her tent at a campsite she had set up about a mile from the trail in Redington Township. She died of lack of food and water, according to the medical examiner’s report, released in January.

Largay’s journal showed she was alive as late as Aug. 6, 2013, and possibly later. The warden service scaled back its extensive search two days earlier, though it continued searches with trained dog teams and thorough grid searches after that and up until the time her remains were found in Redington Township on restricted military land by a private contractor.

Guay said he believes the warden service did all it could to find her.

“It’s tough when you have cleared all the logical areas,” Guay said. “It’s a tough call to make; no one likes to make it. You kind of come to a point statistically where you’re spinning your wheels.”

LOST CONNECTIONS

Every year, about 28 Appalachian Trail hikers get lost in Maine, Lt. Kevin Adam of the Maine Warden Service said shortly after Largay was reported missing.

Most are found quickly: 95 percent of the time, searchers find them in 12 hours. Within 24 hours, 98 percent of lost hikers are found.

The release Wednesday of the warden service report answered questions about what had happened to Largay, but also highlighted how ill-prepared she was for the grueling hike.

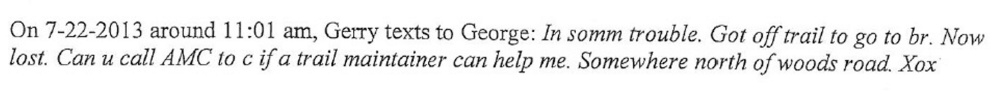

Largay was hiking the Maine stretch of the trail alone, after her friend and trailmate Lee had to leave their thru-hike because of a family emergency. She was relying on her blue Samsung slide cellphone to keep in touch with her husband, who met her every few days with supplies. After she became lost, she tried texting her husband, but because there was no cell service, he never got the message.

“Over my career, I would usually get a call at least once a summer from a family member who had been in cell contact with their hiker and had lost contact with them,” Guay said. “I would ask, ‘Where did you lose contact?’ and it would be, ‘Oh, the Maine border.'”

Shane Vorous, who operates the Stratton Motel with his wife, Stacey, said Thursday that they try to tell hikers where they are likely to get cellphone service and where known dead zones are along the Appalachian Trail.

“As far as cellphone coverage, we do know a lot of where the coverage is and where it isn’t. And when we have people stay here, we try to help them understand where it works and where it doesn’t,” Vorous said.

The former owner of the Stratton Motel, Sue Critendon, reiterated the unexpected remoteness hikers face when they reach that part of the trail.

“Everyone relies on their cellphone so much,” Critendon said. “With a lot of hikers, that is a problem, because there are so many ups and downs in that area, and it is so remote. I think of lot of hikers don’t realize it.”

Both Vorous and Gay were adamant that hikers should carry an emergency locater beacon, or ELB, which when activated transmits a hiker’s location using satellites to allow rescuers to locate them when they are lost. Largay apparently didn’t have one.

“The best thing you can do is have an ELB,” Guay said. “It’s pretty cheap insurance when you are hiking big sections of the trail like that.

Lee, Largay’s friend who had hiked the trail with her until they reached Maine, told investigators that on several occasions Largay had become lost or had fallen behind, and Lee had to backtrack to find her. It wasn’t clear if Largay was taking prescribed anti-anxiety medication at the time.

The report also said that Largay had a poor sense of direction, would become easily flustered, was scared of the dark and scared of being alone.

All these issues are heightened when hiking alone, Guay said.

“What you would have happen (if you hiked with someone), is the calming effect that you’re not alone. If you’ve ever been lost, it adds to panic very easily,” Guay said.

He said that often when someone is hiking alone and becomes lost, they switch their focus solely to survival and not enough on helping themselves be found, as Largay did when she set up her camp waiting to be rescued just a mile off the trail and two to three miles from where she was last seen.

Guay said when people become lost, they should find an open area and try to “catch an eye from the area” by making a fire or spelling the word “help” out with fir boughs. The report documented attempts by Largay to start a fire at her campsite.

“All of those things are critical. Unfortunately, if you’re not moving and you’re not trying to help yourself be found, (rescuers) would have to come right onto you to find you,” Guay said.

MYSTERIOUS DISAPPEARANCE

Largay’s final journal entry is for Aug. 18, though the warden service said it isn’t sure if the date is accurate. An entry Aug. 6 asks that whoever finds her body notify her husband and daughter.

During the extensive search conducted following Largay’s disappearance, searches with dogs came close to Largay’s campsite, including at least once missing it by about 100 yards of where her remains were found.

Adam, who was heading the warden service effort, said shortly after Largay disappeared that the search was “mystifying.”

“We’ve done a lot of tactics that would normally produce results by now,” he said in July 28, 2013. “Why, all of a sudden, did she disappear?”

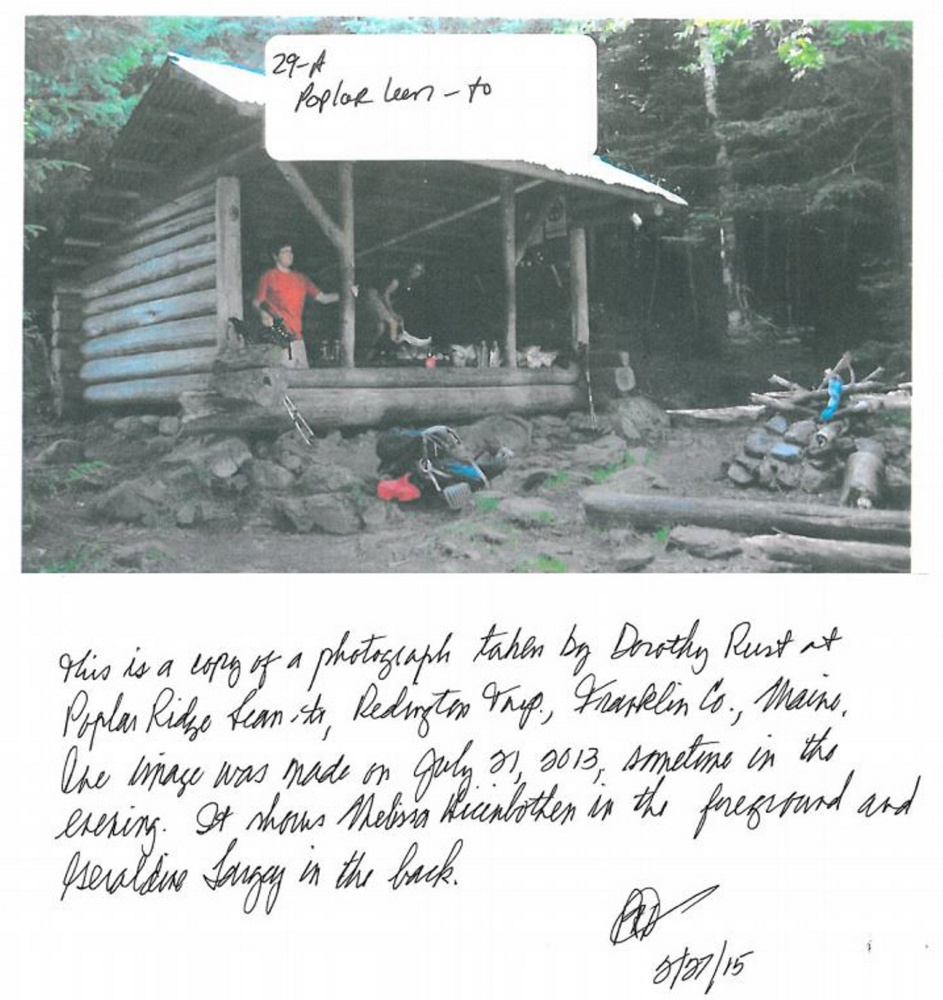

At the time of her disappearance, it was believed, because of a tip that turned out to be false, that she had made it to the Spaulding lean-to — a nine-mile hike from the Poplar Ridge lean-to that she had left around 7 a.m. on July 22. Extensive grid searches in the weeks immediately after she disappeared were to the west of where she was later found, warden service maps showed at the time.

Guay, who has written a book with Maine author Kate Flora about his years in the warden service, “A Good Man with a Dog,” estimates in a synopsis of the book he “has pulled more than 200 bodies out of Maine’s north woods.” In addition to decades of search and rescue experience, he has extensive experience in missing persons/homicide searches and body recovery.

He said that Largay’s case is similar to one of the most memorable in his 25 years as a game warden.

The woman had been missing for four days in the Caribou area, and the warden service had gotten a tip that a woman was seen walking along the side of the road north of where they had originally been searching. But the lead proved to be false. After the search had shifted north, Guay went to double-check an area they had searched earlier, before the tip, and found the woman.

Terrain conditions, wind steering search dogs in the wrong direction, inclement weather, and false tips are only some of the things wardens are up against when the try to find a missing hiker.

But Guay said wardens try to never let it enter their head that they might not find someone, because that is the most difficult reality they have to face.

“It’s hard to tell a family we’ve done all we can do for now until a new lead shows up,” he said. “It’s the hardest thing to deal with as a game warden.”

Lauren Abbate — 861-9252

Twitter: @Lauren_M_Abbate

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.