FARMINGTON — When Nancy Prentiss tells people that she studies worms, she almost always gets the same reaction.

“People wrinkle their noses and go ‘ewww, you work with worms,’” she said.

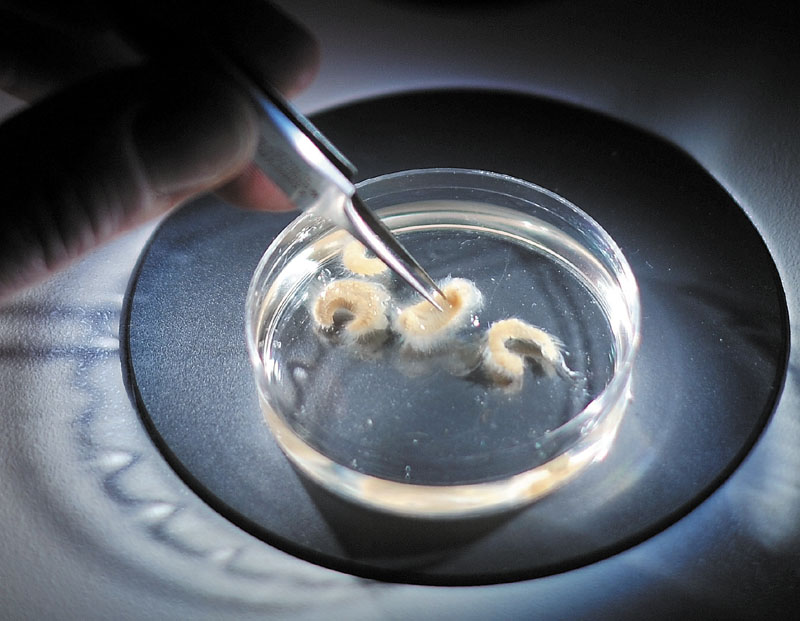

After seeing some of the thousands of marine worms she has collected, most no bigger than a human eyelash, they often change their minds.

“If you just look at them, you’ll realize how beautiful they are. Some of them are extremely ornate and have so many fabulous colors,” she said.

It doesn’t hurt either that Prentiss, a biology professor at University of Maine at Farmington, collected many of her samples while living in a tropical paradise in the Caribbean.

She has convinced so many students about the importance of studying marine worms, a key food for ocean creatures, that they began calling her “the worm lady.”

For Prentiss, 55, her interest in worms began off the coast of Maine, where she started collecting samples during graduate school. It grew into a passion and recently earned her a $33,000 National Science Foundation grant to continue her research in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Prentiss has been studying marine worms in the Caribbean since 2007. The grant is for microscopes, other research equipment and travel expenses to advance her project, which is in cooperation with the University of the Virgin Islands, she said.

She said she started the research as a side project, spending her own money to travel to the islands to collect worms. Then UMF awarded her a sabbatical for the spring semester in 2009 to work on the project, she said.

The extended stay helped to hook Prentiss into a small but international community of fellow marine worm scholars, with about 200 “professional worm people” worldwide, she said.

The first marine worm conference she attended was three years ago in Portland, more than 20 years after collecting her first samples off the same coastline while getting her master’s degree from University of Maine at Orono.

She said she traveled to Italy last year for the annual international conference, another perk of studying something that can be found in any ocean across the globe.

While her work studying and identifying polychaetes, a class of marine worms, is a side project, it has fit nicely with her “primary job” of teaching biology, Prentiss said.

Her office at UMF, where she has taught for almost 30 years, is filled with thousands of vials containing her worm collection. The grant is paying for a special microscope so that her students can better study the collection, she said.

Working with another UMF biology professor, Prentiss has been taking groups of UMF students on 10-day trips to study tropical island ecology in the Virgin Islands, with her sixth group scheduled to leave May 20.

Although the UMF trips are separate from her research work and travel, Prentiss said “my worms” are part of the students’ program. Students gave Prentiss the worm lady nickname because of all the time they spent hunting for polychaetes, she said.

During her research trips, Prentiss also teaches ecology camps for teens who live on the islands. She said her two sons, who attend University of Maine, and her other son, a UMF graduate, often help out with the camps and research trips.

Prentiss said there are thousands of species of marine worms that still have not been identified, with scholars from Australia and other countries planning to join her Caribbean project.

It’s important work because they are a critical part of the “food web” in the oceans, according to

Prentiss, but it also helps teach people that even “plain old earthworms” should be appreciated.

“I’m always trying to change people’s learned behavior to not like squirmy, slimy things,” she said.

David Robinson — 861-9287

drobinson@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.